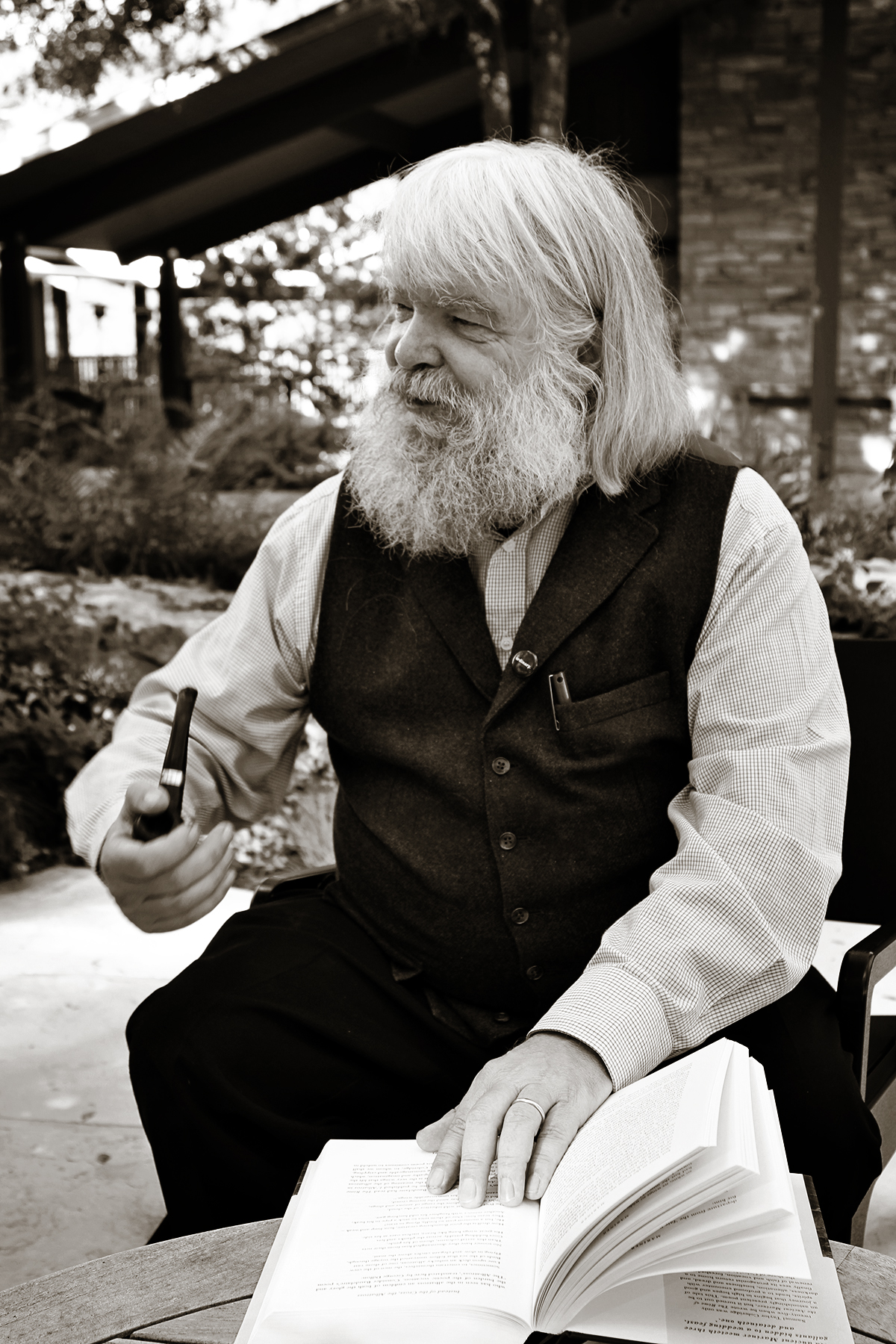

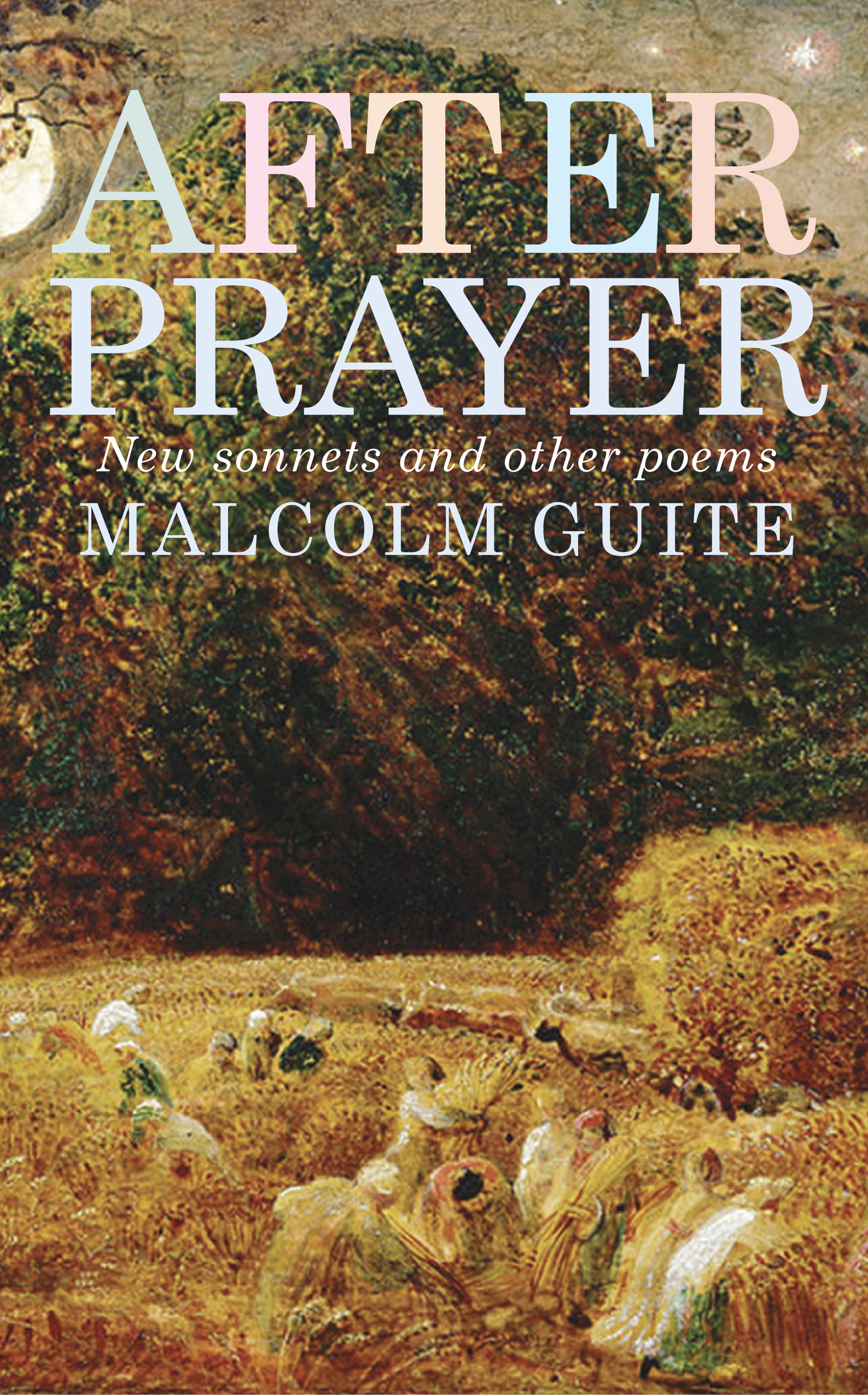

Dr Malcolm Guite is no stranger to Cultivating readers and The Cultivating Project. I have had the privilege of interviewing Malcolm over the course of 8 years covering his books, his travels, and issues that face thinking Christians everywhere. His work as a poet, priest, musician, writer, educator, speaker, and visionary reflect an extraordinary intellect. His life is deeply rooted by a singular and steady pursuit of Christ, and a call to make Him known in ways that are faithfully and particularly good, true, and beautiful. In this interview we discuss his newest book, After Prayer, his long standing connection to poet George Herbert, his involvement in the Ordinary Saints Project, and what comes in his life after this.

Prayer

Prayer the church’s banquet, angel’s age,

God’s breath in man returning to his birth,

The soul in paraphrase, heart in pilgrimage,

The Christian plummet sounding heav’n and earth

Engine against th’ Almighty, sinner’s tow’r,

Reversed thunder, Christ-side-piercing spear,

The six-days world transposing in an hour,

A kind of tune, which all things hear and fear;

Softness, and peace, and joy, and love, and bliss,

Exalted manna, gladness of the best,

Heaven in ordinary, man well drest,

The milky way, the bird of Paradise,

Church-bells beyond the stars heard, the soul’s blood,

The land of spices; something understood.

~ George Herbert

Keeping Company with Herbert ~

LES: Malcolm, you have spent considerable time and attention with the poetry of George Herbert. He shares the chapter “A Second Glance” with John Donne in your book Faith, Hope, and Poetry. His work and presence make frequent appearances on your website and in other poetry collections that you have authored, and you have even written a sonnet for him. In our original interview in 2012 you mentioned that Herbert was one of the influences that shaped your becoming Anglican and finding a place within the Church. With all the company you keep among remarkable poets (Keats, Coleridge, Tennyson, Heaney), what is it that you find uniquely compelling about George Herbert? Why does he linger as a particular influence in your life?

MG: There are so many ways of answering this, because Herbert is an attractive figure in so many different ways, both as a person and as a poet. I think the first feature for me, in both the man and the poet is a kind of inclusive balance and honesty. He writes about both the struggles and the consolations of faith, about both sorrow and joy, and to my mind the consolation, the joy, and the final affirmation of love which animates his poetry, rings all the more true, and is all the more persuasive because he is honest about the sorrow and struggle. As he says in his little poem ‘Bitter-Sweet’:

I will complain, yet praise;

I will bewail, approve:

And all my sour-sweet days

I will lament, and love

But there is also his personal example: the way he brings all he is and has to the twin vocations of being a poet and a priest. As a young man in Cambridge he was known to be dapper, perhaps a little indulgent, with a fine taste in clothes, in food, and wine, a sense of elegance and style. In one sense he sacrificed all that and laid it at the feet of Christ when he forsook worldly life for his priestly vocation, but in another sense, there is a resurrection of those gifts and sensibilities but this time in the service of Christ and his Church, not King James and his court. So prayer itself becomes for Herbert, a banquet, the name and sovereignty of Jesus becomes itself a rich and sensual thing, as in the opening stanza of his poem ‘The Odour’:

‘How sweetly doth My Master sound! My Master!

As Amber-Grease leaves a rich scent

Unto the taster:

So do these words a sweet content,

An oriental fragrancy, My Master.’

To be a poet you must have a certain sensuousness, a certain sensibility to the almost aching beauties of sight and sound. As a priest you must know how to transcend these things, not stop at them, or allow them to become possessions or addictions, but rather pass through them towards their all-beautiful source in God.

Herbert shows me how to do that, and that is why one of his most famous verses, in ‘The Elixir’ has become a watchword, a kind of personal mantra for me:

A man that looks on glass

On it may stay his eye,

Or, if he pleaseth, through it pass,

And then the Heavens espy

It is that quality of ‘throughness’, of translucence, that makes Herbert so important for me.

LES: Herbert said of prayer that it is “the soul in paraphrase”. The 27 word-images that Herbert uses in his poem “Prayer” might be seen as a kind of alphabet through which we can both be in connection with our Maker, but also create a poetic knowing of our own inner being. How do you suggest that we practice using poetry and word-images to deepen our prayer life? Are there pitfalls along the way you might warn us to avoid?

MG: Yes, in fact one might see Prayer as having 26 distinct images, the same number as the letters in the alphabet, and then in the final, 27th phrase, a little coda, to say that through these images we might at last attain to the modest goal of ‘something understood’. So in that sense Herbert may have been deliberately offering the first 26 image-phrases as a kind of alphabet of prayer. I think we come to know the truth as much through images as through words and in my poetry sequence I have taken each of the images in Herbert’s visual alphabet and tried to sense a little of what they might be spelling out for us now. The sequence is the fruit of many years of leading retreats based on Herbert’s poem and exploring with the retreatants how each of these word-images might help us discern both the state of our own souls and also give us new ways to approach God in prayer. One way of practicing this in prayer is to take Herbert’s images one at a time and pray with, and through them; another is to follow his example and make our own cascading list of images and see where they take us. I have done that in my poem responding to his image ‘The Soul in Paraphrase’, in this new sequence.

Of course there are pitfalls in all forms of prayer, and the pitfall here is to get stuck on the glassy surface of our own image and not pass through it or let Christ’s light shine through it, for of course the aim of all prayer, in the end, is to let God’s Spirit bring us back into Christ and Christ back into us.

Life of a writer ~

LES: You close your opening acknowledgements to After Prayer with “to my wife Maggie, to whom this book is dedicated, for the love and kindness that makes my life as a writer possible.” In your own experience, how do you define the ‘life of a writer’ and what does it take for the writer and their partner to make that life possible?

MG: I’m still discovering everyday what the ‘life of a writer’ is, but it certainly involves a kind of fidelity to the craft, a regular, covenanted offering of time and space to the actual task of writing. That means overcoming distraction, self-doubt, not being daunted each time by the difficulty of the task, on the one hand, but on the other hand, it means not being carried away by apparent success, not writing for applause, not depending on reputation, or resting on laurels. In the end it’s quite a practical thing, but it is immensely helpful to have a partner who understands the need for time and space to write, but is also good at keeping your feet on the ground and guarding you against the pretensions and inanities which sometimes ensnare ‘successful’ writers and artists.

LES: As a poet and writer, how do you determine your audience when you write? Are you thinking of someone when you write or are you strictly responding the words themselves as they come forward? What is the role of your Muse in relationship to your intended audience?

MG: I was very fortunate that when I began my first published poetic sequence, ‘Sounding the Seasons’, I didn’t have to ‘determine my audience’ but rather they determined me! For I was not writing in a vacuum or to please myself, but I was writing for, and from within a church community, so there was an element of service and humility embedded and watermarked into the work even before it began. I think that set me free from the isolation and sense of a closed circle that some writers feel.

I don’t always imagine a specific audience for a piece and, even when I have a particular audience in mind, or I am writing a commissioned piece, I still have to be satisfied in my own self that the piece is well-made before I publish it.

I think the role of the muse is vital. For me the muse is both inspiration and audience, I want to feel that I have satisfied the mysterious source from which the poem came in the first place.

LES: When you have an established body of work such as yours written in a form the public has come to identify you with (sonnets), how and why do you make the transition to a different form, even a different tone of voice? What are the risks of writing in the voice that is true to you if the public readership may not find it comfortable?

MG: There are advantages and disadvantages in being associated in the public mind with a particular form like the sonnet. On the one hand working on the mastery of a particular form concentrates one’s powers of expression and channels a flow which might otherwise become too diffuse, on the other there is a danger of repetition or even of self-imitation which would be a disaster. So one has to be challenged and refreshed and that means avoiding routine and re-inventing things. So although I deploy sonnets in response to Herbert’s poem, which is itself a sonnet, most of the other poems in this new collection are not sonnets and some of them are in completely new verse forms which I have not tried before.

LES: A number of the poems in the After Prayer collection explore some hard sides of the human experience. Some of those spaces you have explored in this collection have legitimate and real danger in them. What happens in your own mind and soul when you begin to do the “dark-telling?”, making a written account of the “plummet”, and writing through the dark things naming them openly? Why is it safe to say these hard things truthfully and not always add a comforting close right there?

MG: There is much to ponder in these questions. It is essential for every writer to be honest, not to smooth or cover over experiences of doubt or pain, even if one thinks one is doing so in a good cause. As Heaney says in an interview ‘The faking of feelings is a sin against the imagination’. Accounts of the consolations or joy of faith that simply gloss over the believers experience of pain and doubt simply strike me as false and when they are thoughtlessly repeated they degrade into mere sentiment and convince no one.

You cannot preach the resurrection without the cross, and the great promise in revelation is not that we will never have cried, or have had good cause for tears, but that God will wipe away every tear from our eyes, and God can only do that because, in Christ, He also stood and wept. So we must be honest witnesses of pain and frustration, and yet we must not capitulate to it. In my view the very act of trying to write well about the experience of despair is itself an act of resistance, is one of the ways we transcend and overcome despair.

I realized that in the sequence of images beginning with ‘The Christian Plummet’ and passing through the sequence of bitter pictures of a kind of siege warfare – ‘engine against the almighty, sinners tower, reversed thunder’ Herbert was testifying, paradoxically, to God’s faithfulness, for they occur in the middle, and not at the end of his poem, and the poetry carries him through them. That dark middle-passage concludes with the image ‘Christ-side-piercing spear’, and that of course is the key. Herbert it seems to me, suddenly realizes that God is not in some high castle, being besieged by our prayers but is down here with us, as open and vulnerable, and easily hurt as we are. I put it like this in my poem on that phrase:

Christ’s side-piercing spear

For all the while I hurl my hurts at heaven,

Believing I besiege the battlement,

Of God’s invulnerable heart and haven,

I strike at emptiness, at my own bafflement,

I shake my fist in fury at a shadow.

For he is not like us nor are his ways

Like ours. He left that heaven’s haven long ago

And broke our siege. A voice behind me says:

Why do you weep and rage at heaven above?

I have come down to die here in the dirt,

Your wounds have wounded me, for I am Love

And in my heart I hold your deepest hurt.

Oh turn around, return, and face me here

Your slightest prayer will pierce me like a spear.

Herbert’s example gave me courage to include some of my own darker poems in the second part of this collection, but just as Herbert’s whole sequence ends with ‘something understood’, so my whole sequence ends with benediction even though individual poems may end without consolation.. I did hesitate for a while about including some poems. ‘To make an end’ for example, which is a poem not so much of despair as of sheer exhaustion, of just not having the energy or will to keep going amidst the struggles of life. I had to ask myself ‘Is this poem going to make it harder or easier for someone else going through this same experience, someone else tempted to just give up? In the end I felt that a person reading that poem would feel less alone in their struggle, and of course the poem ends with a resumption of the struggle and the last two words, (Paradoxically for the end of a poem) are ‘ starting now’.

Soul Story and Memory ~

LES: You tell readers at the beginning of After Prayer, “Prayer [the poem] is not a random compendium, but rather a soul-story, a spiritual journey.” The spiritual journey that you both trace and experience through Prayer is a pattern we have seen before in Mariner, your biography Samuel Taylor Coleridge. There is first a warm, open-heartedness. But clouds and shadows come, then ‘the Christian plummet… down into ‘engine against the almightie,’ and later by grace the gradual return to a new, changed understanding. This pattern is much like the pattern seen in baptism – hope and expectation as we enter the water for this sacramental ritual of cleansing and rebirth, then the plunge into the depths representing death, and then the miracle of re-emerging into new life as a new creature. What do you say to the person who is afraid of the dark in their own soul and consequently afraid to take the journey of transformation? As you traveled through the dark of your story in this process of writing this series, were you ever afraid that you would not find the light again or re-emerge safe and new?

MG: In a sense this is a continuation and development of the last question. I would say to that person: ‘it is perfectly reasonable to be afraid of the dark, and everyone who has ever faced the dark has feared it. But fortunately our experience of fear does not change the fact that in Christ the darkness has been overcome and that he himself is, and offers us, a light that the darkness has never comprehended.

The great thing, in the dark chapters, is not to close the book, but to keep telling the story, trusting that we are not at the end of the story yet, and that we are in the hands of a Good Author.

LES: There are recurring themes in the whole body of your work that are particularly evidenced in After Prayer. One of those is the significance of memories and the call to remember. What is the role of remembering in poetic knowledge and the life of a writer? Why must we as writers and poets become guardians of memory?

MG: In one sense all we have as writers is memory. Even the freshest and most recent experience is already over as an outer event and on its way to becoming something significant as an inner event. It is in the act of remembering and retelling that we discover the significance. As TS Eliot says ‘We had the experience but missed the meaning, an approach to the meaning restores the experience but in another form.’ Of course for a Christian writer memory has an even greater significance because Jesus makes memory itself the portal or entry into the great sacrament of his presence when he says ‘Do this in remembrance of me’.

Ordinary Saints ~

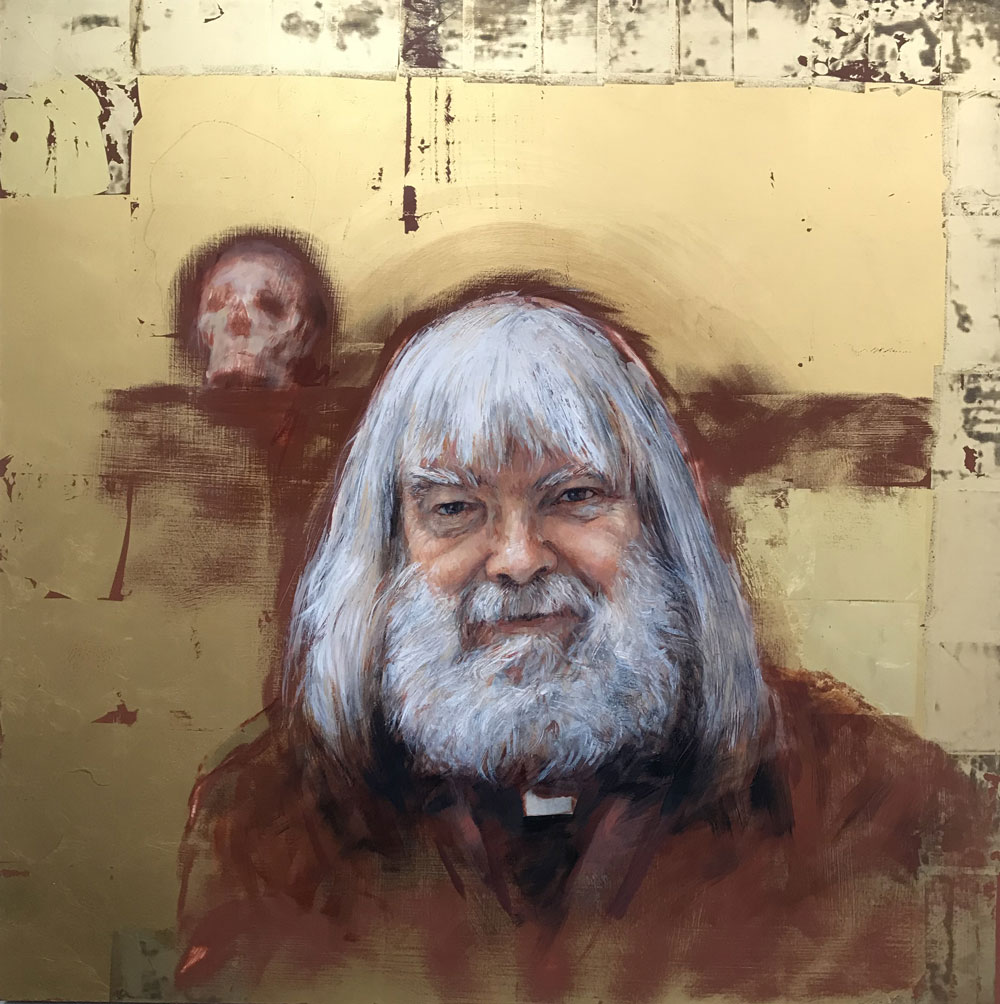

LES: Several years ago you visited the home and studio of painter Bruce Herman to see the process he used in creating an extraordinary set of portraits in a series titled Ordinary Saints. The experience you had there led to doing a collaborative project with him and with composer JAC Redford also titled Ordinary Saints. You share in the introduction to After Prayer, “The purpose of that project … was to meditate on the hidden image of God in each of us, to consider what it was to look through a glass darkly, but also what it might mean to be ‘face to face’, with one another and with God, to see how far our human encounters might become sacraments of grace.”

This project took place over an extended period of time and distance, involving not only the professional skills of three men in completely different creative disciplines, but also required a working harmony and surrender to each other’s gifts that few artists experience. This project was presented in its world premier at Laity Lodge in October 2018 and represented a kind of closure to the project in terms of most of its working requirements. You each have gone on to other life responsibilities and other projects. Looking back through the filter of this past year, do you have a sense of the art worked in you through that collaboration?

MG: Well that collaboration was an extraordinary experience, and whilst it is over in one sense, it is only just beginning in another because JAC and Bruce and I are beginning to travel together, or separately and in our different ways to re-present and unfold that project. We have just done a version of it at Duke University and hope to do one in Oxford next summer.

Looking back I think it was not just the art we produced, the poems paintings and music, but the actual experience of collaboration that taught me most. We discovered how much art arises from the forgetfulness of self and from receptive attention to the other.

We were all three delivered I think from the last shadows of that burdensome modern idea of the artist as some lonely ‘creative genius’ and flourished instead with the notion of the artist as collaborator with and servant of something greater than, and outside himself.

A Portrait of the Artist

“Ah, but we want so much more— something the books on aesthetics take little notice

- But the poets and the mythologies know all about it. We do not want merely to see

beauty, though, God knows, even that is bounty enough. We want something else –

which can hardly be put into words—to be united with the beauty we see, to pass into

it, to receive it into ourselves, to bathe in it, to become part of it.”

~ C.S. Lewis, ‘The Weight of Glory’

There is a presence and an absence here;

The artist sets himself aside, leaves space

For his shy muse. Descending from her sphere

She shimmers through his touch and brush, which place

These faint suggestions of her presence, where

She arches just behind him, full of grace.

He looks another way, as though aware

That turning round to see would frighten her.

He cannot see, we cannot help but stare,

Where light and shade, informing one another,

Call forth the forms that haunt his staring eyes;

Beauties from which not one of us recover.

Beauties of gold and green appear and rise

Behind him like the walls of the Duomo

Which hold the body and its mysteries,

For he has summoned them, like Prospero,

Spirits of air and fire, water, earth,

They haunt him now and will not let him go

Until he paints for them the secret path

Whereby they might grow visible at last,

Until he brings them to their proper birth.

And in their presence we are found and lost:

What finds us here is haunting, numinous,

And opens out the secret of our past

That longing, inconsolable, within us

For beauty, yes, and yet for something more,

Not just to see the lovely, luminous

Appearances of nature, but to pour

Ourselves into and through them, to receive

Them into us, till beauty, grace, and power

Become the very world in which we live,

The air we breathe, the light by which we see,

And we are one with all the things we love.

And what we lose is our complacency;

The daily comfort of the commonplace,

Our cherished substitutes for grace and glory.

These lines of longing in us somehow trace

A portrait of the Artist who has made us

And waits for us to turn and see his face.

3 Finished

For I am incomplete, my mirrors show

No more than flaws and fragments as they pass,

The selves I lose, that mock me as they go,

And leave me trembling by the darkened glass.

I do not see the face that once l had

Nor can I see the one I will become,

Flitting between a shadow and a shade

I was, I was, I whisper, not I Am.

And then comes One who calls me from my ruin,

As from this bricolage of dust and stain,

He works to build what I have broken down,

Outfaces me, and finds my face again,

Just as this artist summons me to see

How grief and joy and time might finish me.

LES: One of the stunning elements in “Finished” is that while this is a personal poem written in response to the creation of a portrait of you, it could also be about me, or any other individual searching for their face and identity being made in progress. It is a personal expression made universal. This poem is so personal and reflective I wonder if it was difficult to share it publicly. As an artist, how do you decide when a piece is something to be shared in the public and when it is meant for more private audiences? Are there times when it is more honouring to keep a piece of art behind a veil? Is that ever true for poetry?

MG: In one sense this poem is an instance of what I was saying earlier. I was delivered from a sense of art as mere self-expression into a sense of art as faithful service, and that meant, paradoxically that when the art itself called for some of my personal ‘stuff’ to be part of the material I could offer it without ego getting in the way, as material to be transformed. In a sense it could have been anybody but it happened to be me. I did learn about myself in the course of sitting for that picture, and in one sense any portrait is a kind of exposure, but the whole purpose was that it should be a personal experience made universal, so I’m very glad that’s the effect it had on you.

Of course there are times when it is better to keep your personal stuff behind a veil and I am in some respects quite a private person. I try not to use my family or home life as examples in preaching and I don’t want to obtrude any of my personal story on people unnecessarily, but there are times when my muse says, ‘this is what’s needed for this poem’, and so I make some part of my personal story available to her.

Seven Heavens and the Medieval Mindset

LES: You have a fascinating sequence of roundels in this collection jointly titled Seven Heavens, Seven Hells. This set is dedicated to Michael Ward, author of the brilliant book Planet Narnia. Could you give us a bit of glimpse into your friendship and joint projects over the years? Has Michael influenced your work or way of seeing things, particularly regarding the medieval mindset? In your own experience as a writer, Malcolm, is there a difference between inspiration and influence?

MG: I’ve known Michael for a very long time and we were chaplains together in Cambridge. We are very different people but were drawn together not just by a common love for the Inklings but also by our faith and literary tastes, and I think by the stimulus of a friendship between two people who are really very contrasted in their personalities and demeanor. We are in many respects like chalk and cheese, though I would hesitate to say which of us was the cheesy one!

We have appeared together several times in the same book but it was only last year that we finally gave lectures together and I think the audience quite enjoyed the differences in style and approach between us. We certainly did.

But on a more serious level Michael is someone whose literary judgment I trust absolutely and he has been kind enough to read in manuscript and advise me about editing and ordering all my poetry collections including this one.

It was he who invited me to write on Lewis as a poet for the Cambridge Companion to CS Lewis, which was a significant step for me and a project that gave me much greater insights into Lewis himself, and of course his book Planet Narnia was a great inspiration, not only for the ‘Seven Heavens’ poetry sequence in After Prayer, but as a great example of good literary criticism.

I think there is a difference between inspiration and influence though you can be both inspired and influenced by the same book.

I think of inspiration as a joyful spark that ignites an entirely new creative work, and of influence as a longer steadier moulding of the mind of a new author by the significant authority and learning of another writer.

Seasons and Benedictions ~

LES: After this journey through such heights and depths facing the human condition, both Herbert and you come back to a basic recognition of the seasons and choose to end the circle with benediction. How do things like seasons and benedictions which seem to come from simpler times maintain a place in a world as complicated and so often degraded as ours is now?

MG: I think they are more needed than ever, precisely because our world is so complicated and its immediate, sometimes hysterical demands can seem so pressing. In contrast, the steady rhythm of the seasons bring us back to the deeper things, the things that remain. The other great advantage of the seasons, both earthly and liturgical, is that they circle slowly round quite independently of one’s own moods and thus become a corrective and offer perspective. I may be feeling glum, but Easter reminds me of resurrection anyway, I may be swayed by some splurge of Christmas consumerism but Advent reminds me that all I really need is the savior who is coming and for whose advent I should prepare. So the seasons, like all the old liturgical patterns, like the practice of reading scripture, can set us free from the tyranny of our own mood swings. In that sense they are always a blessing.

Something understood ~

LES: The closing two words of Prayer are profoundly arresting in their simplicity and pregnancy. What is now understood by you having come through this pilgrimage of your soul-story?

MG: What I love about that final phrase in Prayer is its modesty: ‘something understood ‘ not everything! But not nothing! It seems to me that the academic world swings wildly between thinking it can understand everything and despairing that it understands nothing, and part of its problem of course is that it approaches things only analytically and not prayerfully. I think that one of the ‘somethings’ that I have understood in the course of making this book is that poetry and prayer are not just ways of writing or speaking but that they are in themselves ways of knowing.

Making room for Joy ~

LES: There is so much to love in After Prayer and such a range of emotion and experience reflected here. One of my favourites is St. Augustine and the Reapers. There is a rhythm and an echo of another poem of yours that I have loved and live with every day – The Singing Bowl.

In making the tie between the Psalms and St. Augustine you’ve crossed a span of centuries and made room for us as readers to enter into something timeless. You also cast a pattern for us as fellow pilgrims to follow in kind, making room in our own souls for the choice of joy. I hear traces here from your work in Sounding the Seasons and The Singing Bowl. I also hear an echo of C.S. Lewis’s comment in The Great Divorce, “No soul that seriously and constantly desires joy will ever miss it.” It is not a defeated resignation you imply here in the opening line – “What else can you do but jubilate?” as though we have no other option, but rather an invitation to the ever-waiting Joy.

Joy awaits those who sow faithfully, even in tears, if we will enter its gates. Each of us bear so many sorrows, scars, and disappointments while traveling through our lives. Is entering the gates of Joy as simple as choosing to lay aside our griefs and let go of our misgivings? In the midst of suffering, how do we train our ear for jubilation and make room for Joy?

MG: ‘What else can you do but jubilate’ is itself of course a line of Augustine’s writing about his experience of reading the psalms. He compares the wordless joy of jubilation to the wordless work-songs and chants of the reapers as they bring the harvest in. I like that comparison:

the song of joy is itself the very thing that enables you to complete your tasks in this world and bring in the harvest, but at the same time it speaks of that other harvest when we shall ourselves be brought home to God.

St. Augustine and the Reapers

What else can you do but jubilate? St. Augustine On the Psalms

Augustine hears the sound of jubilation,

A snatch of song, hurrahing in the harvest,

He pauses, poised and open, pen in hand,

Held in the gracious space between God’s words,

And once again his restless heart is lifted

Within and through the song, into the Son.

A wordless song restores to him the words

Of scripture and his psalter breathes again.

Not circumscribed by syllables, but still

Delighting in them, jubilant, his pen

Turns to the furrow, opens the good ground,

So that the seed a psalmist sowed in tears

Might bear rich fruit for us in time to come.

We reap with joy and bring the harvest home.

LES: After such a journey as this, especially on the tails of Mariner, In Every Corner Sing, and Love, Remember, what is next for you? Any season of rest in sight? After that, any chance you may yet pursue the matter of Britain?

MG: Well I certainly hope to have a season of rest, and indeed after one more academic year at Cambridge I intend to take early retirement from that job so as to have more time for writing, but also for being at home and drinking in a little from the fountains of love and learning, rather than just pouring out. But yes, I do have some new books in mind, some already in progress and some just a twinkle in my eye. I gave the Laing Lectures at Regent College this year on the overall theme of ‘Imagining the Kingdom’ and I hope to turn that into a small book. When it comes to poetry I do have a long term project to take up and re-tell some of the Arthurian stories, especially the ones about the Grail, I am beginning tentatively to sketch that out as a book called ‘Merlin’s Isle’ but it is at its very early stages. I am also trying my hand at a novel but it is still far too early to tell if it will get anywhere. Sometimes though, it’s not the works you plan that flourish, but the works that suddenly spring upon you unannounced!

Practice what you have learned & received and heard & seen in me – model your way of living on it, and the God of peace (of untroubled, undisturbed well-being) will be with you.

~ Philippians 4.9

To Practice:

- What have you learned from your own spiritual journey this past year? Do you see a pattern emerging out of it, perhaps something you understand more deeply or with greater peace than you have had before?

- When you face darkness, either through circumstances or within yourself, what practices are you doing now that help you to press on toward the Light? Where do you see the need for help beyond your own abilities? Can you name a strategy for seeking help and encouragement when the darkness seems overwhelming?

- What qualities in Malcolm Guite do you identify from this interview that you might imitate in your own life? Can you name qualities you admire and are drawn to in George Herbert that you also want to model?

All images used in this interview are (c) Lancia E. Smith and used with permission for Cultivating and The Cultivating Project.

Malcolm Guite After Prayer Book Tour Dates:

For further reading and previous interviews with Dr Malcolm Guite:

Lancia E. Smith is an author, photographer, business owner, and publisher. She is the founder and Executive Director of Cultivating Oaks Press, LLC, Cultivating Magazine, and its fellowship of writers and makers. She has been honoured to serve in executive management, church leadership, school boards, and Art & Faith organizations throughout her career.

Now empty-nesters, Lancia & her husband Peter make their home in the Black Forest of Colorado, keeping company with 200 Ponderosa Pine trees, a herd of mule deer, an ever expanding library, and two beautiful black cats. Lancia loves land reclamation, website and print design, beautiful typography, road trips, being read aloud to by Peter, and cherishes the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and George MacDonald. She lives with daily wonder of the mercies of the Triune God and in constant gratitude for the beloved company of Cultivators.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

Really enjoyed this article, is there any way I can receive an alert email every time you make a fresh article?

Chó Shiba, thank you for your kind words. You can receive alerts by subscribing at https://cultivatingoakspress.com/subscribe