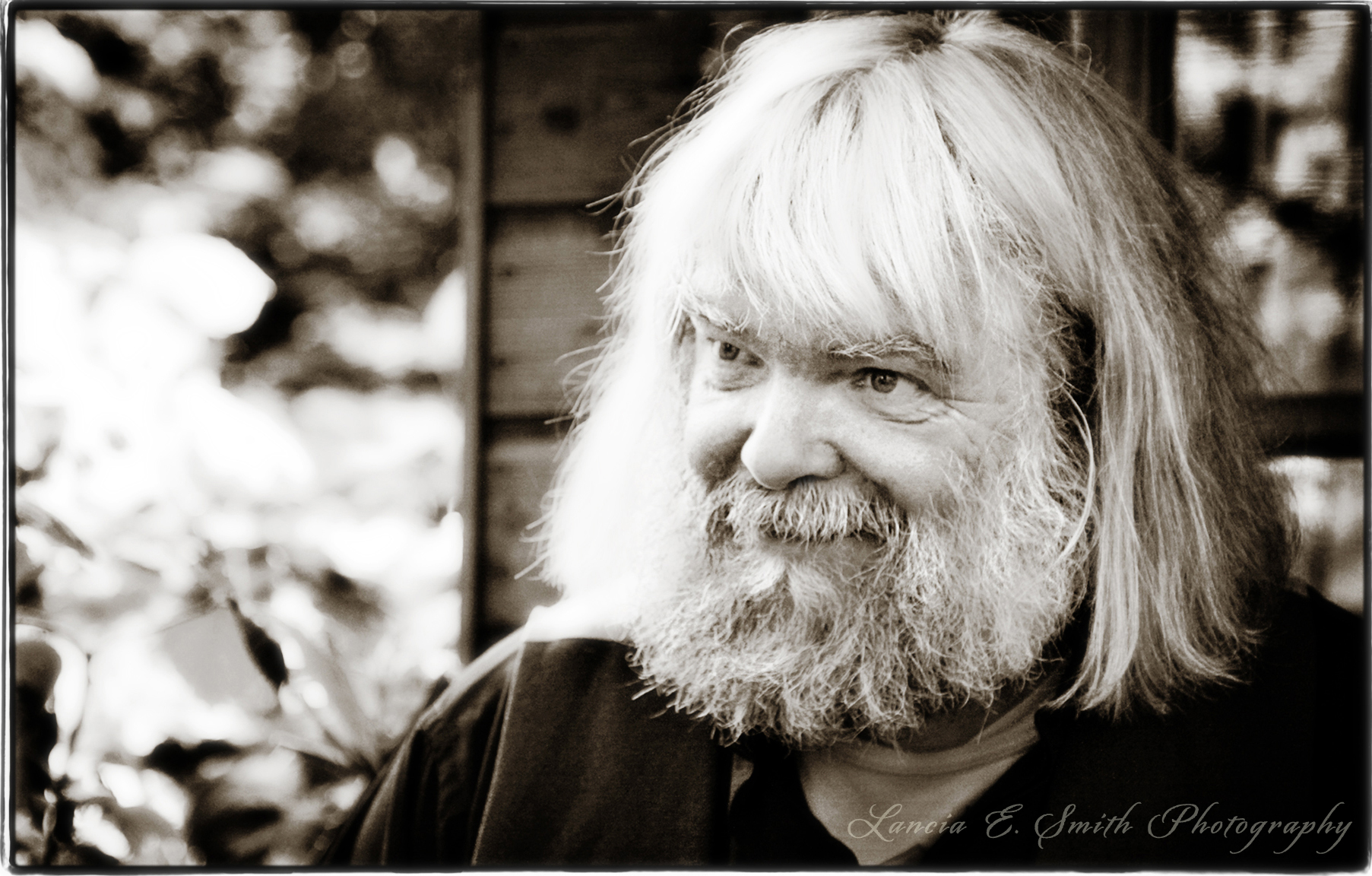

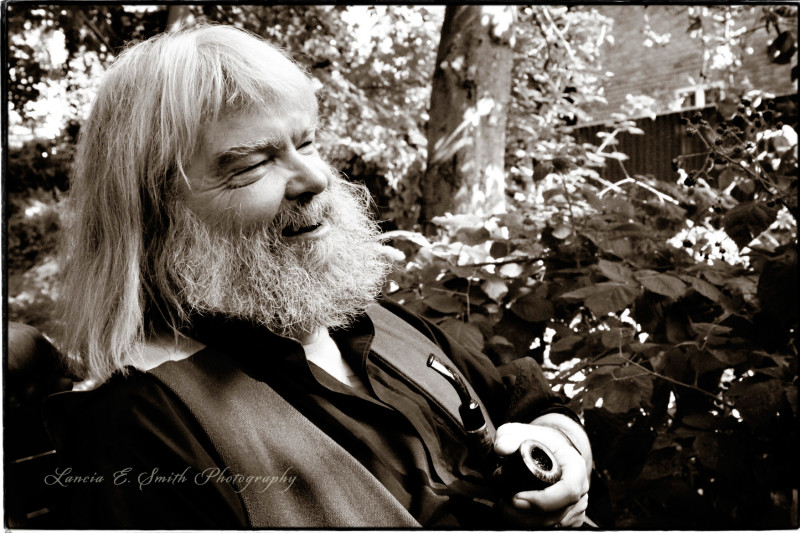

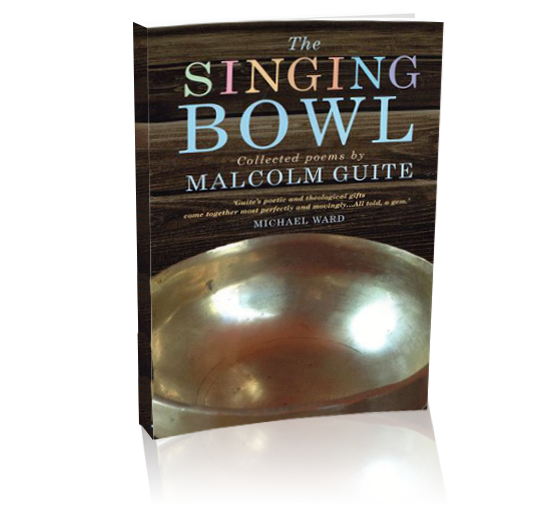

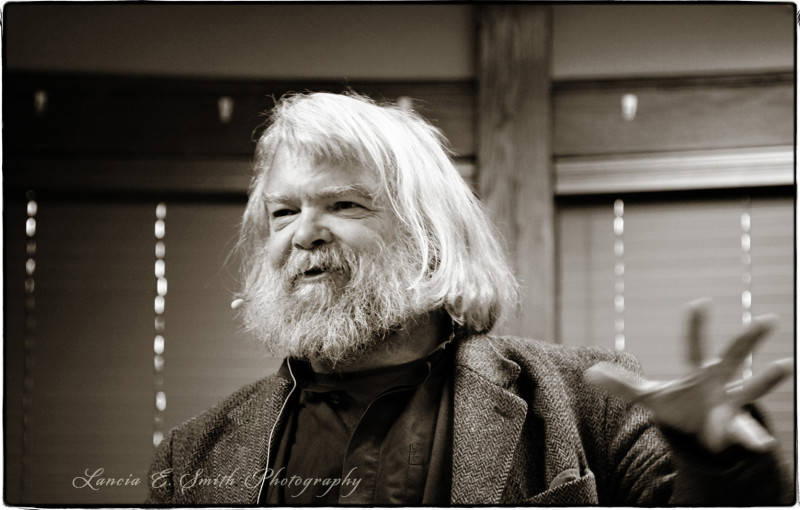

Malcolm Guite is a modern day renaissance man living out the roles of educator, priest, singer/songwriter, and acclaimed performance poet. The author of Faith, Hope, and Poetry; Sounding the Seasons and The Singing Bowl, he lectures widely to enchanted audiences on the topics of literature, poetry and theology. It is my honour and delight to present this interview with Malcolm discussing a handful of the elements he so eloquently explores throughout The Singing Bowl.

LES: The Singing Bowl is a more eclectic collection of your poetry – a net that is wider-flung across a range of themes and styles. In your earlier collection, Sounding the Seasons, you kept within the discipline of a focused topic, the milestones in the Christian calendar year, and used a single poetic form – the sonnet, for that expression. How does mastering the discipline of a single style or specific topic range inform and shape the way you experience your work across a larger range of style and topic? Does the discipline of restraint in one poetic effort influence the “freedoms” of greater range in other efforts?

MG: That’s a very good question! The first thing to say is that there is a paradox at the heart of poetry, and indeed at the heart of of life, which is that restraint brings freedom! Knowing the boundaries and following the disciplines of a given poetic form actually strengthens and intensifies the sense of creative flow, whilst at the same time channeling it into a form that will be sound and harmonious. However within the comparative ‘restraint’ of a chosen form there is an almost infinite variety available. After the intense concentration in and through the sonnet form in Sounding the Seasons I thought it would be good to explore some of that variety of forms which is part of our English literary heritage, so I use villanelles (My Poetry is Jamming’, ‘Salvage’, ‘The Fish and the River’) and terza rima, (‘On Reading the Commedia’) which are both mediaeval forms, Sestinas (‘Six Glimpses’) and Spenserian stanzas (‘Keats’ House’, ‘Out in the elements’) two Renaissance forms, and the ‘blank verse conversation poems’ – a form perfected by Coleridge at the end of the eighteenth century (‘Saying the Names’, ‘Cowper’s View’, ‘The Magic Apple Tree’) as well as a number of other forms old and new,

The variety of topics, which of course gave rise to such a variety of forms –for the form must serve the poem and not the other way round- arises from the fact that my publisher invited me not only to produce new poems on whatever variety of subjects moved me, but also to collect some earlier poems which had previously appeared in small chapbooks, now hard to obtain, or past issues of poetry magazines, so that introduced variety in itself. It also gave me the impetus to revisit and rekindle that wider landscape of memory with new poems too. So for example in the first section on ‘Local Habitations’ I included a poem about the Great Blasket, an Island off the coast of Ireland which I actually wrote whilst I was on the Island when I was 19. But revising it for this collection inspired me to write a new poem ‘In Bewley’s ’about my memories now, looking back on the beginning of that journey to the Blasket.

LES: How do you see these two collections of poetry, Sounding the Seasons and The Singing Bowl tied together? What is the essential thread that you are following?

MG: In the last words of the Preface to Sounding the Seasons I wrote that I was trying ‘to recover in my own small way, what was once a great tradition of more public and accessible poetry’. Sounding the Seasons was written in the conviction that poetry could be lucid and beautiful again without being facile, obvious or archaic, that it could summon an ancient music but still speak with a contemporary voice. I saw The Singing bowl as a direct continuation of that effort of recovery, but applied to a wider variety of thought and form, and I particular I wanted to listen for, and help my readers hear again, a lost melodic line, a singing note, which one can hear so distinctly in the poetry of Keats for example, but which seemed to be missing from much contemporary poetry. That is why the opening poem contains the line ‘Stay with the music, words will come in time’.

LES: How did you become acquainted with the concept of the singing bowl and what is its appeal to you? Why did you use this poem as your title piece?

MG: I first came across a singing bowl in a shop in Cambridge that specialized in far Eastern art and artifacts. There was a mother in the shop with her little girl, looking for silk scarves and she ’played’ the singing bowl for her daughter to show her how it worked, running the ‘beater’ gently round the rim until it trembled into sound. I was enchanted. All the more so when I discovered that these bowls were used to call people to prayer and meditation and that the sound they made was itself understood as prayer. I bought one and brought it home, and that is the one on the cover of the book. We kept it in our hall and also used it to summon the family to dinner! One day I went to ‘sound’ it and it just made a clunky noise because people had started dropping keys and other junk into it. I had to empty the singing bowl to get it to sing again. As I did so I realized that was exactly what God was telling me to do with my life, so the poem emerged from that!

I used the poem as the title piece because it seemed to me the qualities of listening for and making music, and above all openness to all that is timeless whilst still remaining deep within our world of time, were just what I was aiming for in the whole collection.

LES: In the Preface you write, “faith is as much, if not more, at the roots of the poetry than in its branches and blossom. Indeed the sense of being rooted and earthed is an essential element in this collection. If faith is more at the roots of this poetry, what has it become by the time it is in its branches and blossom?

MG: Another good question! The roots nurture the tree and without them there would be no visible blossom or fruit, but the fruit which depends on the root does not have to resemble or refer to it all the time. In ‘Sounding the Seasons’ I made the deep roots of our faith fairly explicit, partly to deepen and nurture them for myself and others. I wanted to make it Clear that Christ the Logos, The Life and the Light is the deep root, and indeed ‘The stock and stem of every living thing’ (O Sapientia). It follows that when I write about anything that partakes of the good, the true and the beautiful, whether it’s dawn at a Northumbrian Harbour, or a walk on Norfolk, a painting by Samuel Palmer, or a wedding ring on my wife’s finger, I am writing about something made and sustained in Christ. But I don’t need to keep mentioning his name for him to be there! He is also praised and glorified whenever we enjoy and praise, in its own way and for itself, the creation which is the work of his hands. Likewise in Christ God has entered deeply into and taken on the whole human experience of pain and alienation, all our suffering. All that darkens our days also overshadows him on Good Friday. In my sonnets on the Stations of the Cross in Sounding the Seasons I made that insight of my faith explicit. But it is still true and I am still aware of its truth when I write about human suffering in The Singing Bowl, and if I do not ‘rush to the compensation’ or offer easy answers as I ask us to stay with five suffering people in the sequence ‘Glimpses’, it is not because I don’t think Christ ‘the root’ is there, but because I want us to remember what it’s like not to know that, so that in the sixth poem we can be with the woman who is praying and share her deep longing to bring our wounds ‘to the wound of One who heals’

LES: In The Singing Bowl, Malcolm, you articulate human experiences that are both ancient and modern, and you use language elements spanning a great bridge of time. I especially am struck by the pieces in Local Habitations and Cloud of Witnesses. Those have a particularly haunting quality. You create a remarkable sense of connection for instance with Samuel Taylor Coleridge. The sense of his person is so intimate it feels nearly tangible. You do the same with creating a sense of Keats’ influence on you in the beautiful poem titled Keats’ House, Rome, and again with the poem for George Herbert. In each of these sonnets there is a reoccurring sense of knowing and yet also being known, a ‘looking at and looking along’. What allows you to develop and experience such a strong sense of connection, a connection with a real and personally sustaining influence on you, with people who have lived in time periods before you? What ties you to a sense of specific places and their unique identities, like Rome and York Minster, Grantchester and San Francisco?

MG: You have touched on something very important here. No one works or lives in isolation, however temporarily ‘alone’ they might be. All of us sprung from a union of two persons, all of us acquired language from other people and that language itself is the living and changing creation of the thousands and thousands of people who share it and of all the previous generations whose experience, speech and writing have shaped and refined it. This is especially true of literature and more especially of poetry. The poet taking up the pen may be at that instant alone in their writing space but the words which are forming in their mind and which will flow onto the page and out from them to others are a gift bequeathed by other generations. And for the poet who is a sensitive reader these words stull carry something of the music and the meanings, the magical associations with which other poets have endowed them. All of us, if we read at all deeply, discover our literary antecedants, we meet our ancestors, encounter our tribal elders, rejoice and play with our kindred spirits, and from all these we learn wisdom. For all of us who write there are the poets we fell in love with, the poets who made us want to be poets too. For Keats it was Spenser and Shakespeare, for me it is Keats and Coleridge, and behind them, Herbert and Donne.

But for a Christian writer this invisible republic of Letters in which every poet is the available friend and teacher of every other, whatever age they were born in, is transfigured into something even more exciting: it is part of the communion of the saints! You may have noticed that in the poems you cited I address Coleridge and Herbert directly, and in the present tense, by name. This is not just because, when you read it feels as if you have the poet with you in the room and you naturally want to turn and talk to them, but also because I believe that they are caught up into glory, that they are aware of us, in God, with the same compassionate awareness that God himself has for us. So when I say to Herbert ‘Help me to trace your Temple, tune your Lute/And listen for an echo from above’ I mean it, in one sense quite literally, under God, and in Christ I am invoking Herbert’s aid!

There is another, very subtle sense in which these poets are around for me, which I can best explain by an analogy. I recently had the pleasure of recording a song in the studio of Roy Salmond, a fine producer who works with Steve Bell among others. Now one of the magic things about his Whitewater studio in Vancouver is that it is full of great guitars, on the walls, on stands, just leaning against the furniture, wonderful, resonant old guitars, all with their stories to tell, all still somehow holding the songs that have been played on them. Its not only inspiring to play one of these as I record and to feel that the others are all there if I needed their timbre or sound for a certain song, but its also the fact that even the guitars I’m not playing are still in the room when I’m recording, they are vibrating in sympathy, somehow adding, almost imperceptibly the little tremors and echoes of their presence. For me that’s how it is when I write poetry, even as I take up my own small lyre I am surrounded by the instruments of all these great poets each capable of sounding a different music. And sometimes as I reach for a certain sound or tone in my own poem its as though I can hear a line of Keats, a cadence from Milton, resonating in sympathy and giving my own new line an inexplicable new richness and depth which always comes as a kind of gift.

There is a parallel sense of added resonance and texture, a parallel experience at once of continuity and renewal that comes from certain special places, ‘local habitations’ that seem to keep a depth of memory or release a stored power of prayer and devotion. I am very fortunate to live in Cambridge and to know as I walk down a given street that Herbert and Coleridge walked there before me. I had a kind of epiphany when I read the Ode to a Nightingale in Keats’ house and much of what I say in that poem about the sense of his presence is literally as well as symbolically true. Places of prayer especially seem to hold a kind of stored force of prayer and presence and release it when it is needed. These places also act as sentinels and witnesses to a shallow or forgetful age of the abiding spiritual truths by which they need to live, which is why I address the building of York Minster itself with the words:

Remember us, your unremembering children.

Stand up old stones, hold in your bones the light,

The dispensation to each piling year

Of Love’s abiding truth

LES: You write the in Preface “The title poem is not my invocation of the muse but rather her admonition to me:

Begin the song exactly where you are

Remain within the world of which you’re made

Call nothing common in the earth or air.

This is her counsel about both poetry and prayer ….” Could you expand on this for us? Who is the muse and why do you have such a sense of peace and recognition with her? How do you recognise her admonitions to you or her inspirations? What is holy about beginning “exactly where you are, remaining within the world of which you’re made”?

MG: For some poets ‘the muse’, if they use the word at all, is just a figure of speech, an easy personification of whatever one means by inspiration. For me it’s a little bit more than that. You will have seen, from all the answers in this interview, that I understand poetry as primarily gift and grace rather than task and achievement, as something received, and shared within community, as something drawn from the mystery of our own depths and communicated to the mystery of someone else’s depths, rather than as something possessed only or primarily by the poet who happens to be writing the poem.

Of course there is an element of task, an element of hard work, of learning your trade, of putting in and giving the time to it, of making yourself available, but in the end you are available to something both in and beyond yourself. You are, as Coleridge put it, ‘Consciously directing an implicit wisdom and power deeper than consciousness’. To speak of a muse who brings and gives the gift, to try to be faithful to her, to listen to her, to be available when she calls, seems to make more sense of all of this than any other way of putting it. I also like the way the traditional language of ‘the muse’ makes her a feminine presence. This works very well for me as a male writer, not only because it appeals to the Romantic in me and allows me to refer to my writing hut as ‘my trysting place with the muse’, but because it allows me to own and acknowledge the feminine element, the alluring, the wombing the birthing element, in the creative process as well as the ‘masculine’ elements in the making and shaping of a poem. We are all to an extent victims of our culture’s narrow gender stereotyping and the language of ‘the muse’ sets us free from these stereotypes, because, whether we have been born a man or a woman there are always both masculine and feminine elements in the work of every good writer. However I wouldn’t want to over-analyze a mystery or reduce it to pop psychology. I think there is very real and in some degree ‘supernatural’ assistance available to anyone who is truly trying to serve their art, and their fellow human beings through their art. In the end we are dealing with a mystery, not an abstraction, a personal mystery, and my muse feels like a very real person; a shy beautiful person who loves music and wishes I would be still and turn to her more often, who is longing to give me more, if only I would give her time. I really meant what I said about her in the poem Muse:

She comes with music, music faintly heard,

A trace, a grace-note, floating in clear air,

As over hidden springs the hazels stir.

Time quivers and then she is at my side;

A quickened breath, a feather-touch on skin,

A sudden swift connection, deep within.

LES: Each poem that goes out into the world has its own unique calling and purpose. A collection of poetry has a destiny that is spun and woven of the sum of all those contained in it together. Sounding the Seasons has a unique purpose and musicality to it. The Singing Bowl while it also has your voice certainly, has a different melody line to it, and really is not simply a continuation of Sounding the Seasons. What do you hope for this collection as it goes out and what do you sense its destiny is as a body of work?

MG: I agree with what you say about a collection of poetry having its own feel, its own purpose and destiny, as it goes out into the world, but I don’t think its always given to the poet to know what that will be, though he has hopes of course! It’s very much like having children. You do your best for them, you always love them, but as they go out into the world they have to make their own friends, get caught up in the lives of people you don’t know, and hopefully become and be for other people all kinds of good that you could not originally have envisaged. I am very glad that some of my poems have gone off into the world and made new friends and some of those friends have brought out depths and meaning in them that I didn’t consciously know were there but which really were there waiting to be discovered.

If that’s true of individual poems then its true of collections too. The big difference between these two collections for me is this: I wrote Sounding the Seasons for the Faithful, to encourage and deepen them in the Faith, to share and celebrate with them the treasures of our great salvation story, and I am glad that it seems to have helped many individuals and churches to do just that. But when I sent The Singing Bowl out into the world I wanted it to go well beyond the circles of the Church, I wanted it to reach poetry lovers of all faiths and none, and to do what poetry does best, as Coleridge says, To ‘awaken the mind’s attention and and direct it ‘to the loveliness and the wonders of the world before us; an inexhaustible treasure, but for which, in consequence of the film of familiarity and selfish solicitude, we have eyes, yet see not, ears that hear not, and hearts that neither feel nor understand.’ Of course I also hoped that even as the minds attention awakened, even as they dwelt more richly ‘in the world of which they’re made’ some of my readers might also experience another awakening, a sense of timelessness resounding into time’, that I might stir the soil of their imagination, ready to receive, in God’s good time, and in his own way, a gospel seed. I might sum that up by saying that The Singing Bowl is the book I would most like my Christian readers to give to their non-Christian friends, because it wouldn’t be an explicit, or an aggressive, or a loaded gift, but it might be a conversation starter!

Here is a link to Malcolm Guite reading To learn more about Malcolm Guite and his extraordinary work here are several resources for you.

2012 Interview with Malcolm Guite – Part 1

2012 Interview with Malcolm Guite Part 2

2012 Interview with Malcolm Guite – Part 3

Malcolm Guite Article on Wikipedia

All of the images of Malcolm Guite presented here are copyright of Lancia E. Smith.

I sincerely hope you enjoy them and that you are inspired to get better acquainted with Malcolm and his magnificent work.

Blessings to you!

Lancia E. Smith is an author, photographer, business owner, and publisher. She is the founder and publisher of Cultivating Oaks Press, LLC, and the Executive Director of The Cultivating Project, the fellowship who create content for Cultivating Magazine. She has been honoured to serve in executive management, church leadership, school boards, and Art & Faith organizations over 35 years.

Now empty nesters, Lancia & her husband Peter make their home in the Black Forest of Colorado, keeping company with 200 Ponderosa Pine trees, a herd of mule deer, an ever expanding library, and two beautiful black cats. Lancia loves land reclamation, website and print design, beautiful typography, road trips, being read aloud to by Peter, and cherishes the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and George MacDonald. She lives with daily wonder of the mercies of the Triune God and constant gratitude for the beloved company of Cultivators.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

[…] chapter on the limits of reason, Kallistos Ware’s chapter on sacramentalism, and Malcolm Guite’s chapter on longing and […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Informations here: lanciaesmith.com/malcolm-guite-and-the-singing-bowl/ […]

[…] Interview with Malcolm Guite – The Singing Bowl […]

[…] Malcolm, you have talked with me before about ‘keeping company’ with many poets, both living and dead, and keep in close communion with […]

[…] up the mountain we can start climbing mountains. No. As the poet Malcolm Guite says, “begin the song exactly where you are.” Tolkien began “The Hobbit” at his children’s bedside in his […]