What a delight to get to talk with David Jack, the translator of George MacDonald’s Scottish novels, and find out more of what is behind the scenes of this fabulous series. George MacDonald’s work profoundly has affected countless readers not only of his work directly but those who have been influenced by him, including C.S. Lewis.

Our many thanks to David for his generous sharing of time and knowledge about MacDonald and his ongoing legacy among us.

LES: David, you are translating a series of George MacDonald’s “Scottish novels”, novels written with conversations in Scottish dialect(s) that previously has left many English-speaking readers unable to follow the stories. How did this project come about and how did you become involved in this effort? What is the order of translation of this series and what is coming next?

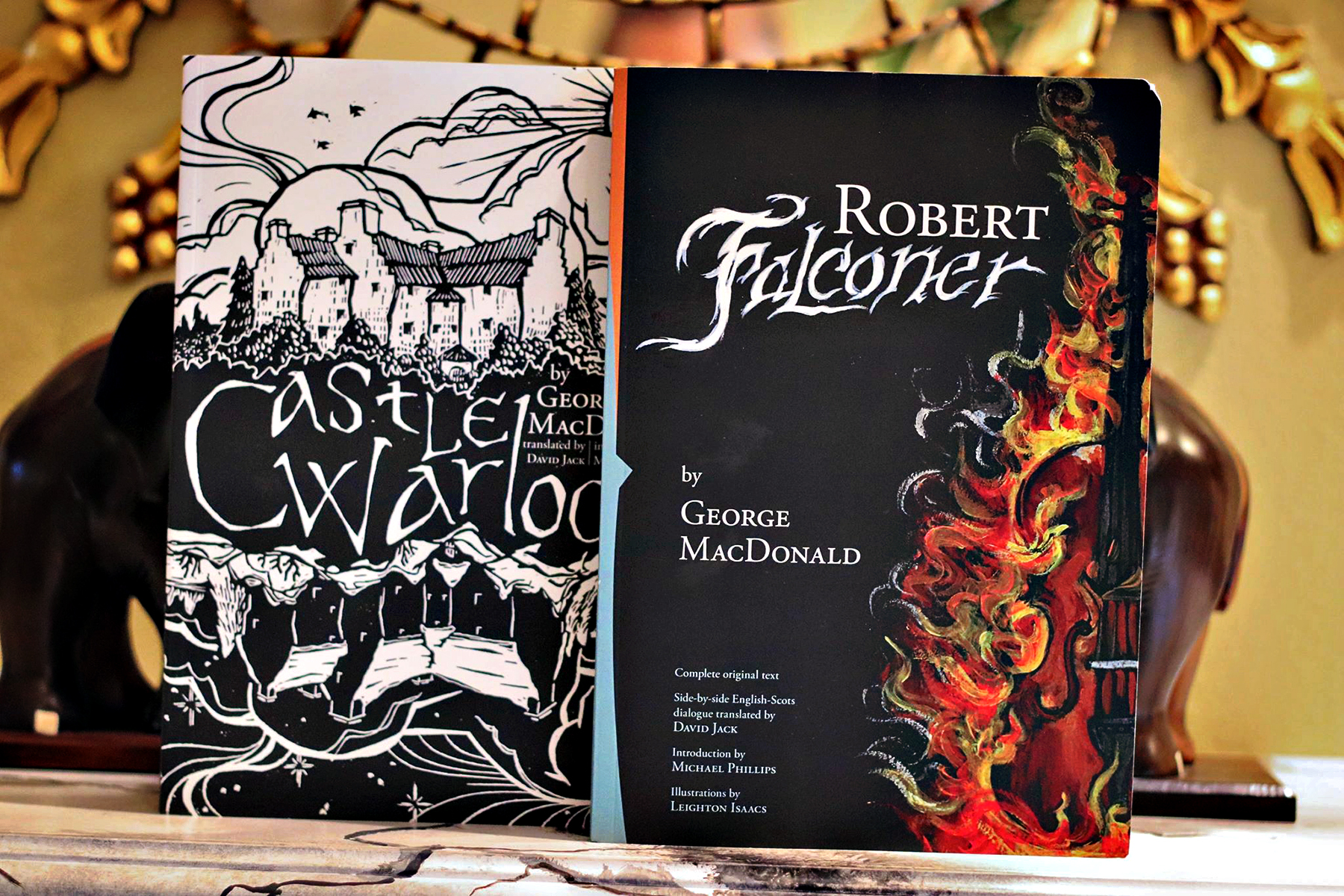

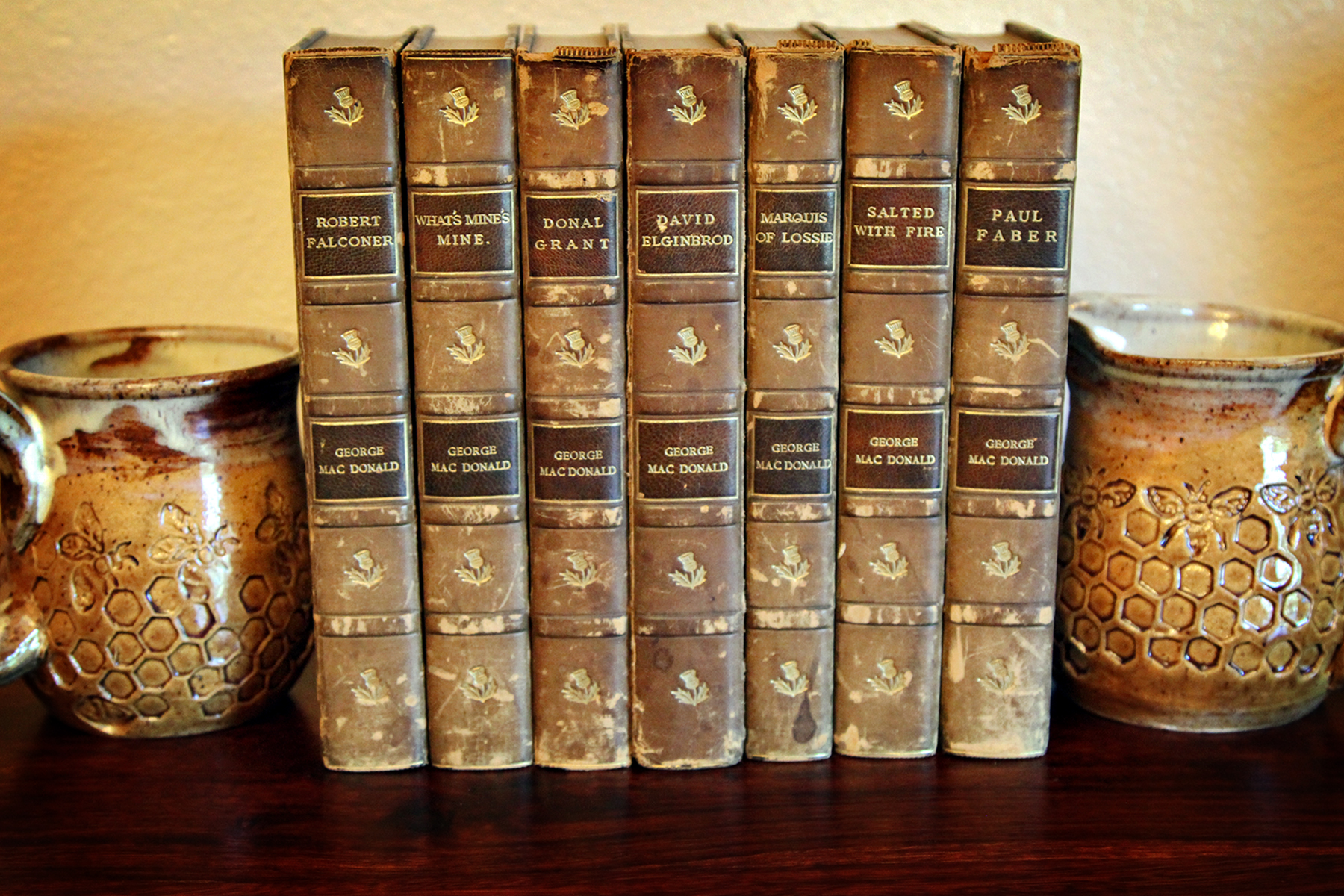

DJ: To answer the last question first, the order is essentially what I choose it to be, since only two of the Scottish novels have sequels: Malcolm, which is followed by The Marquis of Lossie, and Sir Gibbie, whose sequel is Donal Grant. I’m working on Sir Gibbie at the moment (it’s due to be released before Christmas this year) so Donal Grant ought to be next. Gibbie is the third in the translation series-the first two were Robert Falconer and Castle Warlock. The translation project originated online, in the George MacDonald Society Facebook group, where I became known as one of the very few Scottish members (I could expatiate here on MacDonald being a prophet without honour in his own land, but perhaps that’s better left for another time!) and was approached to see if such a project would interest me. The fact that I also hail from the north east just wrapped things up to a nicety.

Geographic Influence

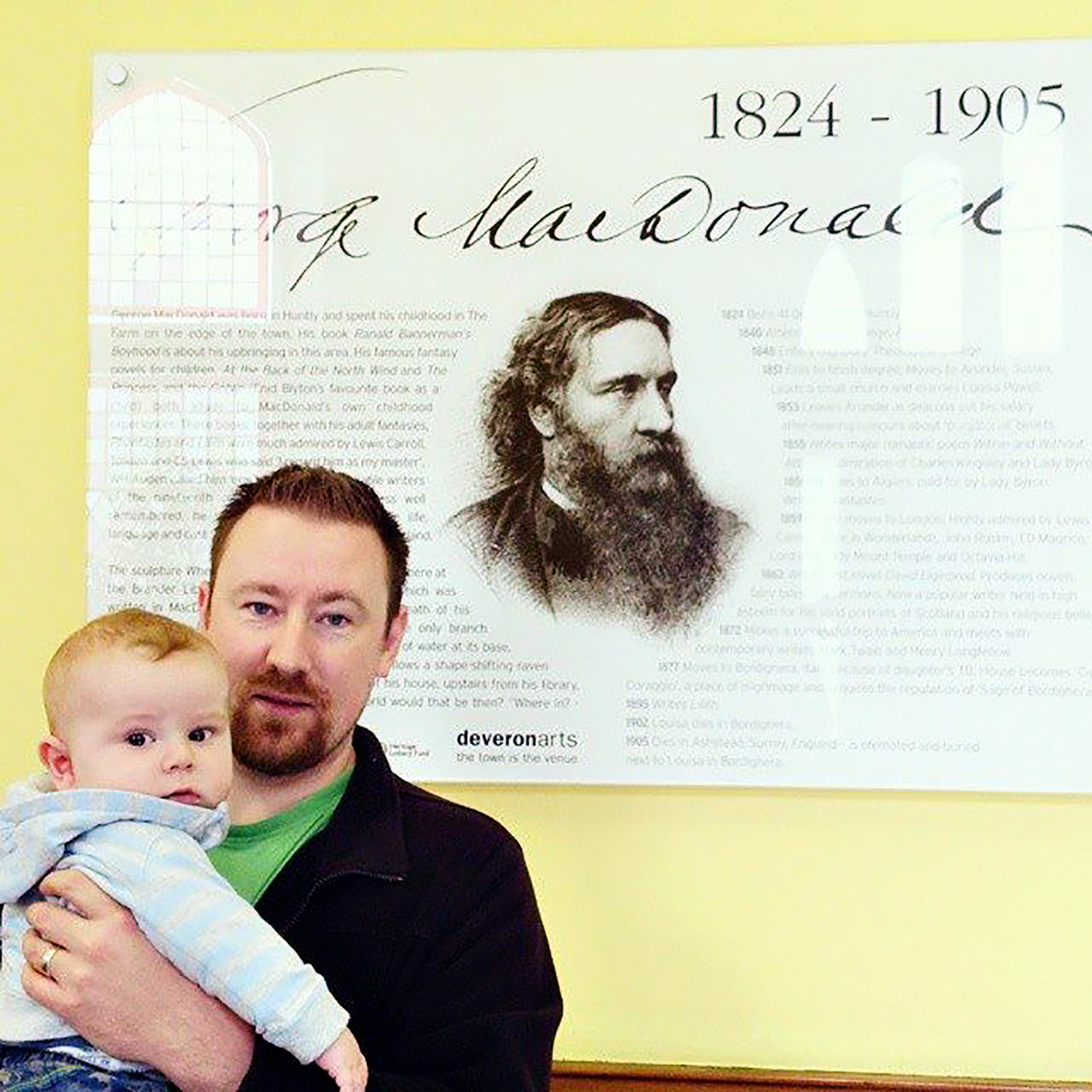

LES: You live now in Perth Scotland, but you grew up less than 50 miles from Huntly, MacDonald’s hometown. When did you discover MacDonald for yourself? Do you have a personal favourite of MacDonald’s work?

DJ: Like C S Lewis, when he famously recalled buying Phantastes, his first MacDonald novel, I can remember the time and place very well. It was 2006, I was twenty-eight, and I was browsing the second hand volumes in a shop in Aberdeen called “Books and Beans.” The particular novel was Robert Falconer, and its effect on me was instantaneous. It is, among other things, an account of a young boy’s emancipation from the toils of man made religion preached as the decrees of God. It’s one of my favourites, because of its timely application to my own experience, but to pick an out-and-out favourite is beyond me. I can see why Sir Gibbie is the best known and perhaps the most beloved of the Scottish novels, but its sequel Donal Grant (another story that combats false religion and its deleterious effects on the human spirit) also has a special place in my heart, and I gave my son the middle name Donal, after the central character.

LES: How does sharing this specific geographic region with MacDonald inform the way you understand him as a person and his written work?

DJ: That’s a very good question. It means that I understand his vernacular, which in itself is more of a key to understanding MacDonald than one might readily imagine. There is an elemental power to simpler and more ancient languages such as Scots, which English has an uphill task to emulate: but of course that’s what I’m attempting-I hope with some degree of success-with these translations (I’m reassured by the fact that when dialogue occurs, we use a parallel text, so the original language is there to be compared with the English column, and to atone where necessary for its deficiencies.) In addition, I am familiar with the characters and character-types of MacDonald’s Aberdeenshire, and with the prevalent religious outlook. Perhaps I can also claim to know a little of the trades that have survived from MacDonald’s day to ours, and that are important to the local communities: my grandfather was a fisherman, and fishing features largely in Malcolm and The Marquis of Lossie-but then no doubt fishermen, as a group, are similar the world over, and are very much the same now as in our Lord’s day in Galilee. Elisabeth Elliot remarked upon how effectively MacDonald portrays God’s love through the “simple life” -though I am slightly paraphrasing there, and perhaps evoking images of Hobbiton that I didn’t intend!

Of Dialects and the process of translation

LES: Douglas Gresham’s understated comment about the old Scottish language and dialects making MacDonald’s work a “touch opaque to those restricted to the modern English usage” is kindly and accurately said. Many modern readers cannot understand what is being said, especially in the dialogues. How many Scottish dialects does MacDonald use in his Scots novels and are some of them more difficult to translate than others?

DJ: He really only uses one, the north east, or “Doric” dialect, because all but one of his Scottish novels take place in and around Aberdeenshire. The exception is What’s Mine’s Mine, a highland tale in which even the Scottish characters speak either English or Gaelic. Their Gaelic conversations, however, are not written down, but merely alluded to by the author, who, as far as I know, was not a Gaelic speaker himself. This novel is due to be part of the translation series, but since no actual translation will be necessary (apart from a solitary Scots poem) it will be the last of the twelve to appear, and will be published mainly to complete the set.

LES: Translation is an exacting process. In the long hours of effort as you work through each word and phrase, do you find yourself loving MacDonald’s work more after being immersed in it or do you ever come close to losing your taste for it? How do you keep your perspective on the material fresh so you don’t burn out?

DJ: My own experience is the greater the immersion, the more joy is to be had from them. I find the subsequent edits much more exacting than the translation process itself, though of course the latter has its challenges. As for keeping a fresh perspective, that is largely taken care of for me by the differences I see in each novel and by their plots, atmospheres, and rich arrays of characters. I like to follow up each suggestive thought, event, or even phrase, of which there are many in MacDonald’s works, and see where they take me. Not infrequently I’ll end up making all sorts of mental connections with ideas found elsewhere in MacDonald’s works (the sermons, fairy tales, poems etc.) or indeed with those of his heirs Lewis, Chesterton and Tolkien, and that in itself keeps me continually entertained and fascinated.

LES: What have you learned from the process of translating that you did not expect to? Has anything caught you by surprise?

DJ: A couple of things I have learned are how thoroughly Scottish MacDonald not only was but remained, after moving to England in early adulthood and then to Italy for the good of his health; and I have also learned more about the Scots language-its power and potentialities – from being afforded the chance to translate these novels.

Literary Merits and Goodness in MacDonald’s novels

LES: The best introduction to MacDonald that I have read is in C.S. Lewis’s Preface to George MacDonald An Anthology. Lewis made no secret of MacDonald’s profound influence on him both spiritually and as a writer. He says that MacDonald portrays goodness and holiness like few others have ever been able to. Lewis also was open about making a distinction between MacDonald as a Christian teacher vs being a writer or as Lewis phrased it ‘a man of letters’. He is unstinting in his praise of MacDonald as a genius of mythopoeic fantasy. As literary critic, Lewis is also honest in his evaluation of MacDonald’s writing style as a novelist. He wrote, “Necessity made MacDonald a novelist, but few of his novels are good and none is very good.” This statement can be misread so easily if not taken in full context. Lewis is simply giving an open-eyed view of what makes MacDonald a compelling writer, even though flawed. Given the work that you do in translating the Scottish novels into contemporary English, how do you evaluate these novels on their literary merits?

DJ: Well, firstly let me say that I appreciate the question, because it gives me the opportunity to correct an erroneous notion that some still hold to concerning MacDonald’s realistic fiction (Scottish novels included) and their relative inconsequentiality. With regard to Lewis, it’s important to begin by putting his remarks in context, as you said. The last thing he would have wanted would have been to dissuade people from reading any of MacDonald’s works, as of course his anthology was compiled for the exact opposite reason! It is true that he regarded MacDonald as uniquely gifted when it came to creating original myths, calling him “the greatest genius of this kind whom I know”, but here we may call Chesterton to our aid and remind ourselves that all of MacDonald’s novels are “disguised fairy tales” and that whatever his merits or demerits as a literary technician, he was first of all a poet, not to say a prophet, who was in a sense too great a man to be boxed in by novel writing conventions. Chesterton seemed to agree that MacDonald was not an elite novelist from a literary perspective, but he almost dismisses this as an irrelevance in the light of his prophetic message. If Lewis didn’t go quite this far, he certainly read most if not all of the Scottish novels, and plundered them profusely for excerpts for his anthology; and we even see him twice prescribing Sir Gibbie in his collected letters as one of the best medicines for both physical and spiritual convalescents. That’s what MacDonald does for the soul. He is so filled with Christ’s spirit, as Lewis said, or to quote George’s son Greville, there was such an “open road between him and God” that to come into contact with him through his novels is to draw nigh to the source of our Life Himself. It is also worth mentioning that Lewis’s verdict, even on the purely literary side of things, is at least partly subjective. The verbosity he mentions is a feature of Scottish, and indeed Victorian literature as a whole, and not everyone would see it as a drawback. These days mere time can be a disqualifying factor for reading the likes of Dickens or Scott, but for all that they have armies of staunch adherents the world over.

LES: What is unique in the Scottish novels about Macdonald’s presentation of goodness itself?

DJ: I would come back to what Elisabeth Elliot said about their simplicity/rusticity. There are certainly characters in his England-based novels who belong to the working classes and to whom the things of the kingdom are first revealed, but I would say they are the exceptions rather than the rule. Nor are they so often “rooted to the soil” in the way their Scottish counterparts frequently are. You feel that the goodness Christ calls forth in these Scottish characters was perhaps the likelier to flourish because they were already like so many Davids or Simon Peters, following lowly callings, but communing with God’s creation as shepherds and fishermen, and awake to divine influences from the first.

Resources and Recommendations

LES: Do you have some favourite resources to recommend for readers who want to learn more about MacDonald and deepen their understanding of him?

DJ: The preface to George MacDonald An Anthology compiled by C S Lewis, which you mentioned above, would be a good starting point for many, since he is most people’s route into MacDonald. My collaborator in the translations project Michael Phillips (perhaps the foremost expert in the field of MacDonald studies today, and editor of the immensely popular abridgements of MacDonald’s realistic fiction) has written a biography Scotland’s Beloved Storyteller. I haven’t read it yet, but I certainly intend to as anything by Phillips on MacDonald is going to be well worth reading. Another scholar who puts my own MacDonald knowledge firmly in the shade is Barbara Amell, and her quarterly magazine Wingfold is a treasure trove of new MacDonald research. Finally-and I’m afraid this one’s harder to get a hold of due to its age-there’s the biography George MacDonald and His Wife by their son Greville, a fascinating first-hand account of the great man’s life and the equivalent, I suppose, of Douglas Gresham’s Lenten Lands, though considerably longer! The introduction by G K Chesterton is every bit as good as Lewis’s Anthology preface, and can be found quite easily online as a separate essay.*

*For online resources, look up the facebook groups C S Lewis and his Master & the George MacDonald Society, and the website The Works of George MacDonald www.worksofmacdonald.com

One additional resource, to clear up any confusion for those familiar with Michael Phillips’ paperback abridgements, is this article, which identifies which Phillips novel (they have all been re titled) corresponds with which original MacDonald work (the books in my new translation series are unabridged, and therefore use the original titles.) http://www.george-macdonald.com/articles/phillips_versions.html

Keeping company with those who came before

LES: “What value is there for contemporary readers to spend their time reading novels written nearly 150 years ago? What can be gained from keeping that type of literary company?”

DJ: I can only answer such a question by saying that truth is truth whenever it is spoken (or written) and that the reason we still read Shakespeare, Bunyan or Dickens today is that there’s a universality to their appeal quite separable from the time or place in which their writings were set. MacDonald himself drew on Novalis, Shakespeare, Burns and Spenser among others, and of course C S Lewis was such a disciple of MacDonald’s that he quoted him constantly, and simply wouldn’t be the Christian apologist or writer of imaginative fiction that we know today without his companionship. The real mystery for me is quite the other way round: why would anyone not want to follow up such openly acknowledged debts (particularly in the case of Lewis and MacDonald) and discover for themselves the treasures hidden in Sir Gibbie, Robert Falconer and the rest? Chesterton in his day seemed to expect, and Lewis at least to hope, that a revival of interest in MacDonald was on its way, simply because his message spoke so directly to our human need-and while the revival may not as yet be in full force, “wisdom is justified by all her children,” since practically all who have discovered him can testify to his stories changing their lives. It happened with Lewis at sixteen, and I hope through these translations the same can happen for other readers today, whether of sixteen or sixty (which is a paraphrase of MacDonald himself, and perhaps a suitable way to conclude our present discussion!)

Lancia E. Smith is an author, photographer, business owner, and publisher. She is the founder and publisher of Cultivating Oaks Press, LLC, and the Executive Director of The Cultivating Project, the fellowship who create content for Cultivating Magazine. She has been honoured to serve in executive management, church leadership, school boards, and Art & Faith organizations over 35 years.

Now empty nesters, Lancia & her husband Peter make their home in the Black Forest of Colorado, keeping company with 200 Ponderosa Pine trees, a herd of mule deer, an ever expanding library, and two beautiful black cats. Lancia loves land reclamation, website and print design, beautiful typography, road trips, being read aloud to by Peter, and cherishes the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and George MacDonald. She lives with daily wonder of the mercies of the Triune God and constant gratitude for the beloved company of Cultivators.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

A wonderfully informative interview, eloquently spoken. i must find more time for MacDonald.

Thank you. Such an in-depth interview and covered so many topics. Thank you, David j.! And thank you, lancia.

Both my Grandparents were from Scotland so I loved reading Michael Philips abridgment of MacDonald’s novels. It made me feel closer to my Scottish roots. I also love CS Lewis and knew of MacDonalds influence was n him. I am so glad to hear that the originals will be translated so I can get a real sense of the Man behind the novels. Thank you for such a fascinating article,

Two things really grabbed me about this interview: 1. Gratitude that someone would take the time to do these translations. 2. This quote: “He (MacDonald) is so filled with Christ’s spirit, as Lewis said, or to quote George’s son Greville, there was such an ‘open road between him and God’ that to come into contact with him through his novels is to draw nigh to the source of our Life Himself.” This is enough to make me read my first G. MacDonald story.

I’ve read all of previous translations back in the 70s. I look forward to reading these translations!

Yes, these translations are certainly a great project, and they seem to be causing a fair amount of buzz. If any of you would like to communicate with David Jack, you can find him at the George MacDonald Society Facebook Group, (which I am not a part of), or you could find him at the George MacDonald Society Goodreads Group, where I converse with him on a daily basis.

A quick update for those who have taken an interest in my translations: the third in the series, Sir Gibbie, has now been published, and is available to order here-http://www.worksofmacdonald.com/products/sir-gibbie-the-scots-english-edition

Wonderful to know! Love the insight.

My father, Ben Campbell, naturally of Scottish descent, introduced me to George MacDonald when I was a child. He lead me to C.S. Lewis and Tolkien. I treasure his books and look forward to reading your translations. We’re in transition now so all my books are in storage, but I have Lewis’ anthology of MacDonald and more:) Looking forward to sharing with my son, Ian.

This interview is loaded with information and insight. Thank you so much!

Thank you, David Jack for taking on this worthwhile project and to you, Lancia for getting the word out! What a wonderful excuse to re-read this edifying works!