It is my great joy and privilege to share this interview with author and beloved friend Sarah Clarkson with you. Sarah’s friendship with the great ideas of story, imagination, and belief are matched by the beauty with which she lives. I know no other writer in all the world who can write about incarnation the way Sarah does.

We both pray that you will find here, and in the great books we discuss, the encouragement you need to flourish in the story God has written for you.

LES: Sarah, why Book Girl? Why a “woman who reads”? Why not boys, too, and men who read? Much of what you’ve written in Book Girl could apply to both genders. Do you have a specific purpose to writing especially for girls and women?

SC: Let me open by saying I’ve searched my own soul about this, because I would be heartily glad if men read and came alive to the reading life through this book. I even had a couple of men on my launch team, readers who shared my passion and love for story and recognized themselves in the pages of Book Girl. (One podcaster told me her father read the book and proclaimed that he too was a ‘book girl’).

But Book Girl is at heart a story, my story. The book is directed to female readers not because it isn’t applicable to all readers, but because Book Girl is the story of my journey as a woman reader.

In speaking directly to the way that books formed me and excavated the deepest places in my soul and psyche, I simply had to speak as a woman. I think I’m a writer who’s at her best when writing from the interior. The deeper I got into the writing of Book Girl the more I understood that what I wanted to create wasn’t a pedantic or directive work, but rather something more in the vein of a memoir with book lists, a witness to the comfort and grace of the reading life as I have known it from inside my soulish seasons of quest or delight, depression or new understanding.

I wanted it to be a work of almost incarnational particularity, the reading life in this soul, this memory, this woman’s story, something that thus opened up the possibility for my readers of the reading life as present and possible to their own particularity.

But a second reason is actually by way of my deep thanks to the community who surrounded me as I created this book. Book Girl emerged out of a season in my life when I was rediscovering my capacity as a learner after a long spate of self-doubt, struggle, and a real loss of confidence in my own vocation as a writer or my capacity to actually succeed as a creator or as a student (as I then was and am now again) at Oxford. Over three tumultuous years I discovered my own capacity to create, to endure, to come into my power both as a woman with a confident voice and a writer capable of the work I desired. A major part of that renewal came through the friendship of women peers, mentors, and a dear tutor at Oxford (and you, my dear friend, who opened my Oxford time with a gift to help me ‘flourish’). Book Girl thus emerged from my gratefulness for women readers who empowered me in my identity as a learner, a writer, a reader, and that was a distinctly feminine gift that I wanted to pass on in the pages of Book Girl.

Books about Books

LES: You’ve written several books about books including, Caught Up in Story about character formation through reading. Why write another book about books? How are these two different from each other and how do they ‘keep conversation’ with each other?

SC: On a basic level, my first two books were written to parents and teachers but were primarily about children and their relationship with books, while Book Girl is written to adult readers as adults. I’ve given many talks to parents on the power of reading, and inevitably, in conversation afterwards, someone will always approach me to say, ‘I’m determined to give the gift of reading to my child, but what if I never received it? How do I begin if I’ve never been a reader?’. This is a book for those souls.

The driving idea for me in each ‘book on books’ I have written was my deep sense that the reading of books is a vital, life-shaping habit, a way of living and ‘living to the full’ which is at the heart of the Gospel. In reading, the eyes of mind and imagination are sharpened to spot a bit more of the fullness of God’s reality, ‘at play’ (in the words of Gerard Manley Hopkins) throughout creation. The fact that I felt compelled to write three books on the subject of reading is witness to my own journey and development in understanding what reading so marvelously accomplishes in our hearts and minds, shaping identity, forming our loves, and why it is demonstrably in decline as a daily habit across every strata of society.

I am driven by the conviction that reading must be defended, that it needs to be rehabilitated as a delight and gift in popular habit and imagination. I hesitate to compare myself for even a second to that giant of writer, C.S. Lewis, but one of the things I have most valued in reading his essays on story and imagination was the way he gave articulation to the reality of Joy, to the deep insight that can come to us through a work of imagination. I remember reading his essays and feeling this vast sense of relief; that I wasn’t heretical in thinking that a novel or a myth could sometimes mediate God’s reality to me in a way I rarely encountered in more formal doctrine. Lewis gave me, a brooding teenage reader whose spiritual life was being powerfully formed by Middle Earth and George Eliot, permission to embrace the fact that I truly could encounter God in the realm in story. But in so doing he also helped me to understand why the faculty of imagination was something worth fighting for in an age of reductive materialism. His very gift of imagination articulated also made me aware of why it is suspect in our age and at the same time, armed me to defend it.

In my own very small way, I hope my writing will have the same effect on the endangered habit of reading. Books are something we take for granted and because of that, they are a vital part of human experience that I think we are honestly in danger not just of losing, but of forgetting. In an age of social media and constantly evolving technology, the act of sitting down with a book seems old-fashioned, even boring to eyes used to the swift movement of click bait.

I’m heaven-bent on alerting the world to the gift of good words and empowering good folk to choose and defend the reading life. I think three books on the subject is enough. But you never know.

Seismic cultural shift

LES: Sarah, I think we are seeing a new resurgence of a longing to read again and let our ourselves wander in quieter, richer places. Karen Swallow Prior released On Reading Well and Anne Bogel released I’d Rather Be Reading on the same day as Book Girl released. I see this as a reflection of a cultural move toward books and the need to find sustenance in well written words that offer a deeper and truer narrative to follow. Do you sense a cultural shift occurring in our attitudes toward reading itself? What might be triggering that shift?

SC: I do. I think a renewed value for the reading life goes hand in hand with things like the slow-foods and local buyers movement, with our renewed interest in the handmade, the handcrafted, the rooted and deep. The reading life is a distinct and formative way of interacting with the world that is radically different from the rhythms of the online world. The internet is sleepless, and the information we find on it endless. We have endless choice and too many activities. So much of our life via screen abstracts us from the present, drawing our consciousness into alternative realities, away from the particulars of this moment, this place, even our own interior lives and thought. Reading operates on us in a powerfully opposite way, drawing us away from the pace of the instant into the quiet of this page, this moment, this light filtering in through the window.

As with all of these things – local foods and rooted lives and community development – reading allows us the possibility of a certain kind of or quality of existence, it gives us the grace of slower sight, a way of existing in the world apart from the rush. The reading life is a choice for a centred self, for eyes alert to the present and aware of its wonders, of a heart able to be attentive to those to whom we are bound day by day in work and love.

I also think we are beginning to recognize that reading, especially when it comes in the form of great novels (I would argue), translates and explains us to ourselves and each other in a profound way. We are beings of imagination, living stories whose forward narrative motion is hope and desire, fear and guilt. A great story makes sense of that, helps us to untangle the mixed motives of our broken hearts and yearning souls, shows us to ourselves as the possible heroes or heroines in our own small tales. List of facts or headlines or status updates simply do not provide that interior excavation and illumination we so desperately need.

Holy Defiance

LES: In a world rushing by faster and more frenetically every day, how do you give yourself the permission and the grace to read slowly?

SC: I think the resistance of rush is a holy defiance, one we must all embrace! I sometimes think the relentless modern bent toward ever increasing and depersonalized efficiency, rush, and almost brutal productivity is devilish. We try to live at the pace of the online, but the internet isn’t human; it doesn’t have needs or limitations or loves. It is a machine, and when we live as machines we burn out more swiftly than we could have imagined.

The same applies to reading. We aren’t informational machines who read in order to come to higher efficiency. We are living beings spoken into existence by a living Word, created to grow into our capacity and potential by our encounter with Scripture, with story, with the living narratives of the people around us. That is a gift and way of existence that cannot be hurried, something my restless, driven self has come to understand after long years of striving.

I am able to give myself grace to read slowly, to savor, to mull and reflect because I am living the reading life… and it is just that, life. And that’s an idea I was keen for readers of Book Girl to grasp. Reading is not a race or an achievement, you’re not meant to get more points for having read more books. You’re meant to discover the power of words to kindle your vision, to companion you in seasons of depression or grief. Reading is a way of coming alive to the fullness of the world, to the presence and interior reality people other than yourself. Reading often heals our sight because it slows us down. Knowing that, I have come to recognize that its not so much permission I have to give myself in order to read slowly as much as it is a grace I have to learn to receive.

In my restless teen years when I burned for action and meaning I discovered (much to my chagrin) that one of the most oft-repeated words in the Psalms is…wait. One Psalm in particular, 37, became almost amusingly present, whispered to me by the Holy Spirit in countless small crises of identity of purpose and driven by one word in particular ‘dwell’. Dwell in the land and cultivate faithfulness. This image of life, one in which we wait in an expectant, hopeful faithfulness for the leadership and goodness of our Creator is, in a way, an image of what I desire in my reading life as well.

To read is to dwell in imagination, in thought, it is to receive the great good that is coming to us in countless ways through the gift of good words. And that is a process that simply cannot flourish in rush.

The reading life & the space to flourish

LES: What exactly is the “reading life”?

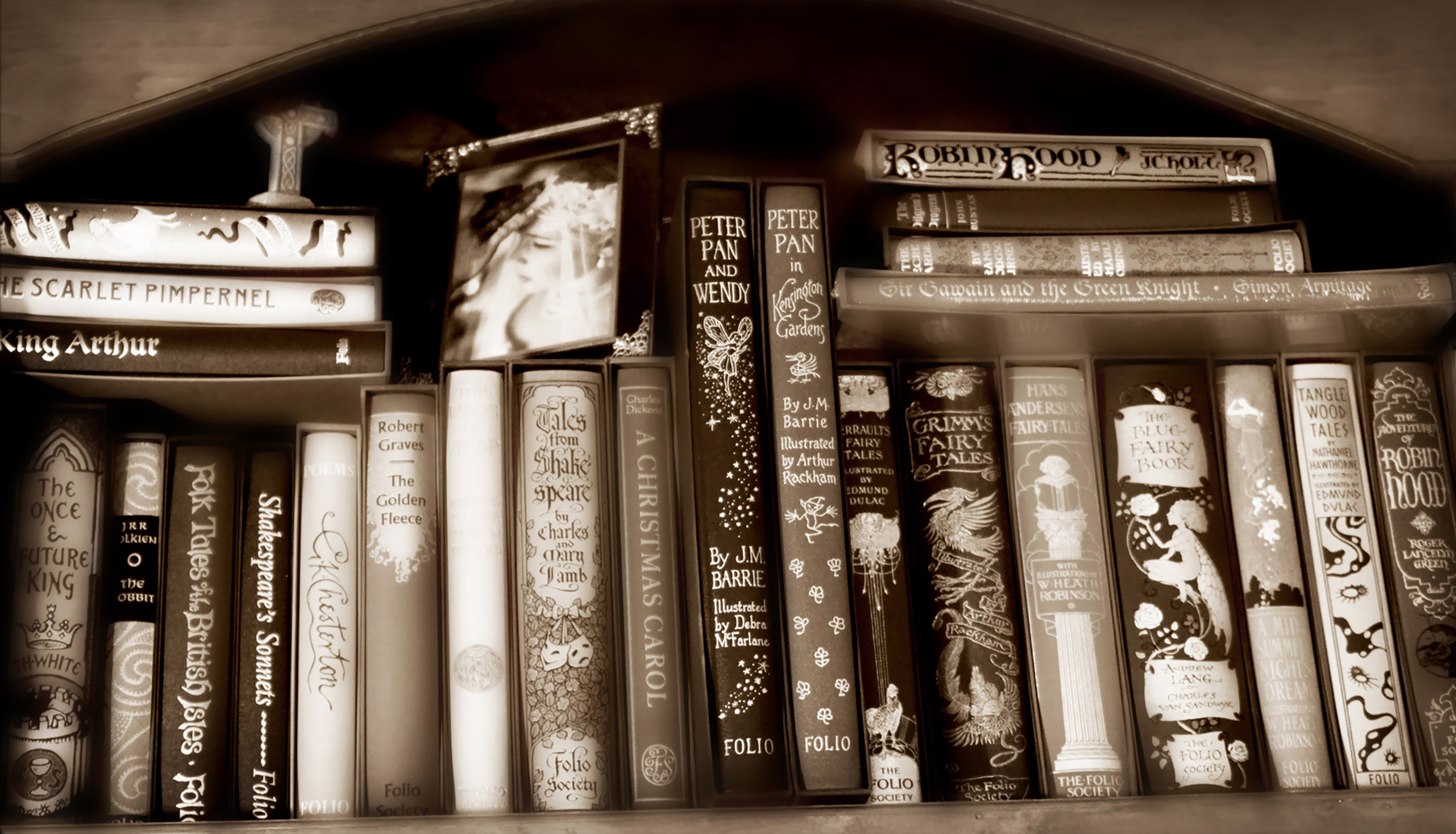

SC: Here I get a bit breathless. The reading life means days marked by the gift and rhythm of words; Psalms in the morning and poetry at noon, novels to cheer the lagging hours and epics for the evening. The reading life is a way to grow into that fullness described by Paul in Ephesians 3, a way of more fully discovering ‘the length and breadth and height and depth’ of the love of God as evidenced, explored, and sparkling in novel and memoir, biography and poem. The reading life is one of wonder, in which a line of poem or a novel’s spare phrase illuminates the landscape of our own small story, ‘sets the sight on fire’ in Plath’s words. The reading life is one of hope, in which the happy ending works upon us like Tolkien’s ‘eucatstrophe’, as grace, letting us taste a ‘joy beyond the walls of the world’. The reading life is a way of connection, a means of seeing the world through another’s gaze, of expanding our own sense of the possible. The reading life is our heritage and gift, a way of recognizing our own lives as great stories, our means of taking the hands of wisdom and joy, jollity and grace as we journey homeward.

LES: Something I loved in the early part of Book Girl is the section where you discuss how to enter into a rhythm of reading and where you write about the importance of choosing based on “knowing what I value and making space for it to flourish.” What do you recommend for readers who may not yet know what they value or have the courage to make space for flourishing?

SC: I would say first, know that the Creator of the world crafted you to embody a particular facet of his own beauty. His delight in what he has made is one I think he yearns for us as human beings to share. And while that may seem a grandiose place to begin in answering the question, I think it’s fundamental because it is in our knowledge of being intimately known and painstakingly created that we find the permission to discover ourselves more fully, to seek out the identity that is our glory and gift. To know our Creator’s intent for us is our empowerment to create space in our lives for self-discovery and the first thing I would say is this: claim, as a treasure, as a heritage, as a radiant right, a space of regular time in which to know yourself; to identify your desires and hopes, to articulate your dreams, to figure out if you even yet have any dreams! For me as an introvert, that means weekly space. I’m actually writing this in the Saturday morning, coffee shop quiet that is my husband’s great and weekly gift to me (while he sits with our six-month-old daughter).

Second, I’d say to you what my spiritual mentor here in Oxford said to me; nothing is too small for a beginning. I was lamenting my total inability to have a real quiet time after the birth of my daughter. I could barely concentrate on Scripture, I felt very little desire for prayer and all I could manage daily was the reading of a letter or two from my collection of Henri Nouwen’s correspondence. I was expecting a lecture on discipline and what my mentor said instead was this: draw a mental circle around that daily reading of a single letter and claim it as your quiet time. If all you can do is read for five minutes, ask the Holy Spirit to invade that space. I say the same to you. As you discover yourself, as you grow in insight, as your heart begins to move in desire, draw a mental circle around certain points of your day and claim those as the space in which you will listen for the Holy Spirit’s whisper, in which you will grow, or learn, or… read.

Books that lead toward glory

LES: Sarah, what is the role of discernment in our selection process of choosing what to read? What does it mean to choose books that lead us toward glory?

SC: Oh, the lovely C.S. Lewis. I have so many times been struck by his words in his sermon The Weight of Glory about the fact that each one of us is (I paraphrase), in our smallest daily choices on our way to becoming a creature of nightmare or a creature more beautiful than we have imagined. When I was wrestling with how to articulate a philosophy of discernment when it comes to reading, that was the image that finally came to mind.

I found it difficult to write the chapter on discernment because I am so wary of legalism. I could tell you ten rules to follow in choosing godly books but I think that would be to limit the play of the Holy Spirit in the varied stories of the world and in the very particular stories we are each living. But I am also convinced at the level of bone and blood that we are called, in every area of our lives, including reading, to grow in holiness, to grow in that Beauty we glimpse in the person of Christ.

Lewis thus gave me a way of centering my philosophy by presenting me with the idea of our progression toward Beauty as being a criteria for evaluating the influence of each book upon my mind and heart. I think a really health capacity for discernment is rooted in a vision of goodness, in an encounter with Beauty himself, usually in the pages of Scripture. When we have hearts and appetites and imaginations formed by the narratives of the Bible we already have a pretty healthy faculty of discernment because we can evaluate the books we come across based on the truths they tell about the world. Do they tell the truth about the frail and faulty nature of the human heart? Do they speak of the possibility of redemption? Do they close the horizons of hope or leave them open by way of forgiveness or creativity?

When I consider what effect a book has on me – feeding the fires of love and hope or dulling my sense of evil or invigorating my compassion or leaving me in despair – when I consider which of the Lewis images it is creating in me, I am able to choose with a little more clarity.

Freedom through discipline

LES: Would you expand a bit on what is meant by “a mind made free by discipline”?

SC: There’s a quote in Old School by Tobias Wolff where the Robert Frost character addresses a schoolroom full of young men enamored of modern poetry because it has thrown off ‘form’:

“I am thinking of Achilles’ grief, he said. That famous, terrible, grief. Let me tell you boys something. Such grief can only be told in form. Form is everything. Without it you’ve got nothing but a stubbed-toe cry—sincere, maybe, for what that’s worth, but with no depth or carry. No echo. You may have a grievance but you do not have grief, and grievances are for petitions, not poetry.”

Discipline is form, and our reading needs form and discipline, care and attention if it is to become a force of insight and wisdom, joy and wonder in our lives. A free mind isn’t one that deals in spontaneous, unfettered ideas, like a river overflowing its banks. A free mind is one that is capable, muscled, insightful, able to discern truth and reject deceit, to claim and embody the beauty it finds, to create, eventually, in its own turn. This is the kind of mind that grows out of the kind of reading to which we bring the whole of ourselves. I’m not saying you shouldn’t sit down and let a novel rush through your imagination – heaven knows this makes up a healthy chunk of my reading. But I am also deeply aware that when I muster my consciousness, when I interact with the words before me, when I am present in own mind to the mind of the writer, wrestling, arguing, loving, making notes, when I am in that sense disciplined, the muscles of my imagination grow taut and strong, my capacity to think clearly expands, and I know my own creative power to shape the world. That’s what I mean by a mind made free by discipline.

The truth that beauty tells

LES: One of my favourite lines in Book Girl is “A woman who reads is a woman who has been prepared to accept the truth that beauty tells.” Where do you see your best examples of the numinous in the books you have loved?

SC: Oh, what a delightful question. A whole cascade of scenes floods my mind as I think over the passages I have read. I think of Emily, with her ‘flash’ in Lucy Maud Montgomery’s ‘Emily’ series:

And then, for one glorious, supreme moment, came “the flash.” Emily called it that, although she felt that the name didn’t exactly describe it… it had always seemed to Emily, ever since she could remember, that she was very, very near to a world of wonderful beauty. Between it and herself hung only a thin curtain; she could never draw the curtain aside–but sometimes, just for a moment, a wind fluttered it and then it was as if she caught a glimpse of the enchanting realm beyond–only a glimpse–and heard a note of unearthly music.

I read that and felt instantly that someone had articulated what I, in stumbling hunger had tried to describe as a ‘knowing’, an instant in which the encounter of beauty in some form allowed me a direct knowledge of goodness in a way that left me trembling and delighted, yearning and alive. It’s Lewis’s ‘Joy’ all over, but I loved the way Montgomery described it for Emily, the earthy, ordinary realms in which she found it.

I think of that scene in Tolkien’s Return of the King, in which Aragorn is recognized as the king he so fully is by his capacity to heal his people ‘for the hands of a king are the hands of the healer’. I encountered that when I was in a phase of despair, struggling with a diagnosis of OCD and with my own deep hurt at the hands of my church. I had wrestled for months with God’s goodness, unable to imagine his tenderness toward me until I encountered that scene (I’m getting teary as I write this) where Aragorn labors over Faramir, calling him back from the brink of death.

Suddenly Faramir stirred, and he opened his eyes, and he looked on Aragorn who bent over him; and a light of knowledge and love was kindled in his eyes, and he spoke softly. ‘My lord, you called me. I come. What does the king command?’

And it was as if my own soul said the same to the Christ I rediscovered in that moment.

I think of a luminous passage from Michael O’Brien’s novel Island of the World where a young boy, abused and alone, sits in prison despairing until another chained and wounded man gives him hope:

“Do you see?”

Josip shakes his head.

“Surely you see,” says the man.

“I see the light, but the walls imprison it.”

“The light has entered the prison. Nothing can keep it out.”

“If there is no window, the light cannot enter.”

“If there is no window, the light enters within you.”

And I learned something of love’s relentless pursuit of the hurting and lost, the ones who believe they are forgotten.

I think of the scene in Elizabeth Goudge’s novel (you knew I had to get a Goudge mention in, right?) Gentian Hill where Stella sits up under a hazelnut tree and is given an instant of vision, of unified sight and a sense of Love at heart of the universe…

Wait. You’d better stop me now.

Sovereignty of mind & three heroines

LES: Could you share with us a bit about what it means to “reclaim the sovereignty of my own mind”? Why is that so necessary and how is it possible to do that in such a scattered age?

SC: I’m a total self-led amateur in this area, but I am fascinated by consciousness studies. It began with my discovery of Owen Barfield’s work on consciousness (developed in conversation with C.S. Lewis), his assertion that ‘poetic diction’ (the language we encounter in poem or novel) has the power to give us a ‘felt change of consciousness’. I mention this because I think the idea of having sovereignty over my mind has a lot to do with reclaiming my consciousness, my gaze, and that is a process aided by words.

We live in an era where our consciousness is increasingly dictated (and our attention fragmented) by our focus on our screens. Now, I love much about the online world, I love the community and beauty that have formed in some of its corners (this one in particular), so I’m not demonizing all online presence. But over the past years I have observed my own increasing distraction, my inability to focus, my impulse to turn to my iPhone in times of distress or fear or need or even boredom. I have watched my capacity to engage with the world around me in person and creation and the world inside of me in imagination and prayer be greatly threatened by the presence of screens in my life, by the way they suck me into the endless stream of online information, the never-ending feeds with their addictive, bite-size chunks of fact or opinion.

To regain sovereignty over my mind for me has meant a halt to that pattern. For me it has meant banning the iPhone from the bedroom and refusing to look at anything online before my quiet time (and these days, before Lilian’s first nap). I do this, not out of some sense of guilt, but out of the joy I find when I wake in hush and can hear the Lord whisper to me in a Psalm or in the growing light out the window because I have time to see them again. I do it because it helps me to be fully present to my little daughter’s first waking moments (realizing that her eyes follow mine everywhere helps with the conviction). I do it because I want my own ideas and convictions to be rooted in the deep quiet of prayer and contemplation, where I hear the voice of God, rather than in the ever-shifting miasma of online opinion.

LES: Out of the wide sea of women characters that you have met and loved in your reading, who are three you most want to emulate or embody as your life unfolds.

SC: This is a very hard question to answer. I have seven characters, at least, but I will (with great discipline and pain) limit myself to three for the purposes of brevity. Let me say also that these are not characters I necessarily feel that I am very ‘like’, but I want to embody their creative shape of presence in my own life.

First, Lucilla Eliot in Elizabeth Goudge’s three books The Bird in the Tree, Pilgrim’s Inn, and The Heart of the Family. She is a charmingly wilful, creative, passionately loving matriarch who understands that the great work of her life is to create a home that will be the refuge of her family. Stumbling out of the loss of her favorite son (her unabashed favoritism amuses me) in the trenches of the First World War with an orphaned grandson and her own broken heart to cope with, she comes upon an old house whose walls are soaked in a kind of holy love and she claims it as a place of embodied hope, a corner of the earth where beauty will reign and love will hold sway despite the vagaries of the broken, modern world. I hope to create just such a place myself. I have no idea where it will be (I’m married to a soon-to-be priest in the Anglican Church and will probably live in a series of vicarages quite soon!), but to forge that claimed, rooted space that is actually a witness to the reality of the eternally good and beautiful is one of my lifetime hopes.

Second, Hannah Coulter in Wendell Berry’s novel of the same name. What I love about her is the way she roots herself in her ‘place on earth’ (title of another Berry novel) and is a lifelong philosopher about it. Hannah Coulter is in many ways just the inner history of a farm wife. But because of that, it is the history of a heart capable of recognizing the presence of divine love as it blossoms up in the faithfulness we give to person and place, the integrity of work, the long story we weave in love when we give ourselves without reserve to those we have vowed to love. I want to be a woman like her who lives a profoundly faithful life in the vital details of the ordinary – and recognizes the eternal good she is weaving.

Finally, I’m going to also say George Eliot here, though she is an actual, historical character, because I feel I have so profoundly encountered her mind in her novels and in the biographies I’ve read about her life. I love her fierce questioning, her hunger to know. She was a reader and intellectual, a writer whose words formed the imagination of a generation. She was a woman who saw ‘the mystery behind the real’, who taught me to ‘hunger after truth and beauty’, who was so distressed at the un-Christlikeness of the Christians she knew that she left Christianity, and mourned for Christ the rest of her life. She was a woman who saw human character, in its fallenness and frailty, its mixed motives, for what it was and yet recognized the way that a divine love could glimmer up through it in the actions of forgiveness or compassion. I love her for her honesty, her compassion, her practical idealism, her superb novels and agile mind. I would love to be a little like her in any of those areas.

Home & Story

LES: One of my favourite quotes of G.K. Chesterton appeared in a little publication called Tremendous Trifles. He said,

“Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon.”

As you think of the world that Lilian will grow up in – the beauties and the bogeys both, how do you best teach her that beauty is stronger than despair, and that dragons can not only be fought but can be beaten?

SC: There were definitely several distinct moments during my pregnancy that I sat in a sort of blank befuddlement looking out my window at a grey Oxford sky thinking… how in the name of all that’s good can we raise a child to wholeness in this crazy world?

When it comes down to it, I’m placing my hope for Lilian’s wholeness on God and two basic gifts, gifts I will fight and work and strain to give her again and again.

Home and story.

Home, because I want her heart to be rooted in the knowledge that she is loved, and I want her to grow up in a space in which love is embodied. Love, both divine and human, enfleshed in our dinner table and our candlelit moments, our reading times and laughter and music, even in the tenacious hold of affection through disagreement or grief or stress. If she can know she belongs to us and to God, held in an affection that will not change or cease throughout her life, and if she can ‘taste and see the goodness of the Lord’ in the stuff of our ordinary, I believe she will have some sense that Love is original and ultimate, the beginning and the hoped for, fought-toward end of her existence.

And story. The more I study theology (its my subject here at Oxford), the more I am convinced the Christian faith is something that comes to us largely as narrative, a story that draws us out of the false finality of death into the ever active, ever broadening story of redemptive life in the Incarnation. We encounter this reality most powerfully, not in static, doctrinal statements alone, but in stories, in the vivid, vital narratives that image to us what it means to believe in beauty and defeat the dragons of the fallen world. This is the gift I want to bequeath to Lilian; an encounter with Scripture as her own true story, her own real epic, the narrative in which she has the chance to act as heroine. With this ultimate story, I want her imagination crammed and formed by other great stories, by the best literature of the ages, by a host of imaginative companions teaching her how to see, how to love well, to choose beauty, to fight bravely.

In the final chapters of The Return of the King, the hobbit Sam wakes from what he thought would be death to find that he is safe in ‘the keeping of the King’. Sauron has been defeated and Gandalf, the beloved leader and friend whom he believed dead, is waiting to greet him. Shocked and dazed with joy he gasps, ‘is everything sad going to come untrue?’

I think stories like The Lord of the Rings help us to a powerful knowledge of that truth, something I hope Lilian will find as we live the reading life together.

A favourite set of words to hold to

LES: Do you have a favourite quote that captures a sense of the life you want to live?

SC: Well, I’m greatly tickled by William Yates description of his wife (Elizabeth Yates, also a writer) and have always thought I’d be honored to have this said of me: ‘She has plenty of courage, a strong faith, and a native expectancy of good. Living with her is a high adventure.’

But I’ll go with this one from George Eliot as I took the title of my blog from her words and have long found it to be a quote that set me on my writerly feet and made me want to live with integrity and an alert, active love:

‘It seems to me that we can never give up longing and wishing while we are thoroughly alive. There are certain things we feel to be beautiful and good and we must hunger after them.’

The images included in this interview are (c) of Lancia E. Smith and used with glad permission for The Cultivating Project.

Lancia E. Smith is an author, photographer, business owner, and publisher. She is the founder and publisher of Cultivating Oaks Press, LLC, and the Executive Director of The Cultivating Project, the fellowship who create content for Cultivating Magazine. She has been honoured to serve in executive management, church leadership, school boards, and Art & Faith organizations over 35 years.

Now empty nesters, Lancia & her husband Peter make their home in the Black Forest of Colorado, keeping company with 200 Ponderosa Pine trees, a herd of mule deer, an ever expanding library, and two beautiful black cats. Lancia loves land reclamation, website and print design, beautiful typography, road trips, being read aloud to by Peter, and cherishes the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and George MacDonald. She lives with daily wonder of the mercies of the Triune God and constant gratitude for the beloved company of Cultivators.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

Add a comment

0 Comments