“This book is written partly in answer to requests that I would tell how I passed from Atheism to Christianity and partly to correct one or two false notions that seem to have got about. How far the story matters to anyone but myself depends on the degree to which others have experienced what I call “joy.” . . . The book aims at telling the story of my conversion and is not a general autobiography, still less “Confessions” like those of St. Augustine or Rousseau. This means in practice that it gets less like a general autobiography as it goes on.”

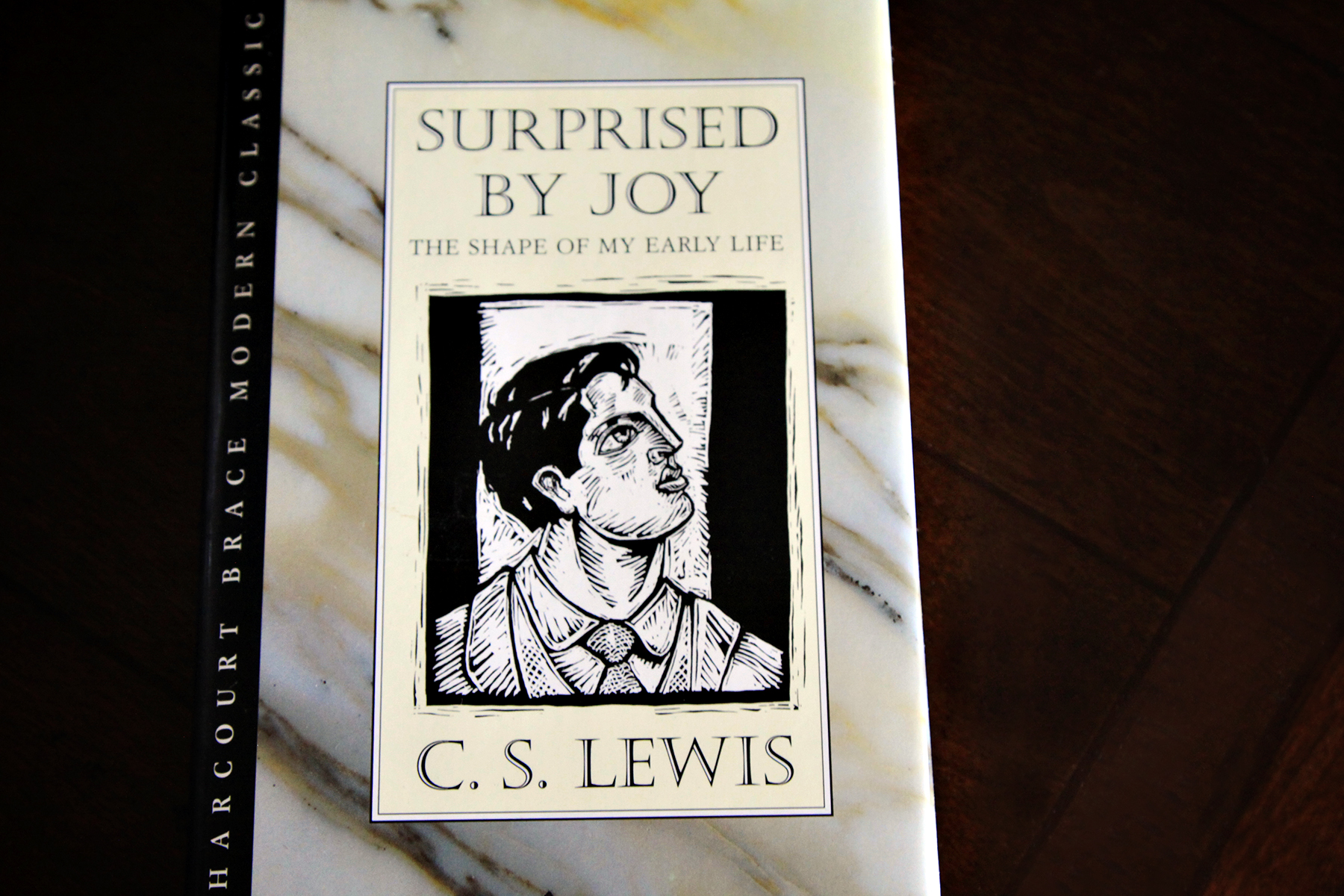

With these opening words to Surprised by Joy,[i] C.S. Lewis draws a line in the sand of bygone years.

His account of conversion takes us from his birth in Belfast, through his school years and post-WWI fellowship at Oxford University, to his final “checkmate” moment during a drive to Whipsnade Zoo.

But, as promised, this book is no mere chronicle of times and places.

Lewis’s journey to Christianity threaded as much through inner landscapes as it did external experiences, wending between the green Castlereagh Hills and the annals of Norse mythology, across the woodlands of Phantastes and the poetry of George Herbert. Like a will-o’-the-wisp in a marsh, a peculiar, “inconsolable longing” called to him at these sites, drawing him away from familiar pathways of thought. He chose a simple term for the phenomenon: Joy.

Joy sought him out in his childhood, eluding his grasp ever afterward, until it revealed itself to be an emissary of the King of Kings.

This story is well known to many, and I am one of the Joy-riddled “others” in his audience who owe a tender and grateful debt to Lewis for naming this yearning. Over a decade after my first reading of Surprised by Joy, he still reminds me that my homesickness leads not only to the threshold of heaven, but to Christ Himself. I’m sometimes tempted to preserve the exquisite stabs and stings that come my way, but Lewis’s experience loosens my grasp. I remember that sparks of Joy are sure to dim; bottled up, they will lose the spark of life that made them precious to me in the first place. For Joy is, at its heart, “valuable only as a pointer to something outer and other” (238).

Lewis saw Joy as the lodestar of his conversion, and he did not think it possible to build his narrative around any other theme. “[I]n a sense the central story of my life is about nothing else,” he writes. But his admission also holds weighty implications for us, I think; it raises the possibility that, in our own lives, there might be a main river into which all our day-to-day tributaries feed. What story is being spun in them?

How does the past appear when one’s sight is sharpened by eternity?

A Good Preparation

School was not an easy place for young Jack Lewis to be—starting with an institution headed by “Oldie,” a man who exhibited signs of insanity. Neglect, irrational guidance, and physical abuse marked the long days there, and both imagination and intellect fell into disrepair. To fill up the time between lessons, all the pupils were made to do arithmetic; Lewis’s brother Warren performed the same five sums every day for years.

Yet Lewis is remarkably kind in his retelling. “I could continue to describe Oldie for many pages,” he confesses; “some of the worst is unsaid. But perhaps it would be wicked and it is certainly not obligatory, to do so” (29). We see more of the grown man than the schoolboy here, both in the writerly restraint that Lewis exercises throughout the book, and the forgiving lens with which he views the people in it.

And he goes further. As he looks back on this past season, Lewis invites us to see how God “meant it for good,” (Gen. 50:20, ESV):

[T]he year was not all term. Life at a vile boarding school is in this way a good preparation for the Christian life, that it teaches one to live by hope. Even, in a sense, by faith; for at the beginning of each term, home and the holidays are so far off that it is as hard to realize them as it is to realize heaven. They have the same pitiful unreality when confronted with immediate horrors. Tomorrow’s geometry blots out the distant end of term as tomorrow’s operation may blot out the hope of Paradise. And yet, term after term, the unbelievable happened. . . . In all seriousness I think that the life of faith is easier to me because of these memories. (36-37)

Not even these seemingly wasted years escaped the wave of redemption that later crashed into Lewis’s life. Their curse became a gift—one that went on to enrich others. “The term is over: the holidays have begun,” proclaims Aslan at the end of The Last Battle. We know this is not a lightly drawn analogy, and perhaps that explains the indelible power of those simple words to move and thrill so many readers; they are the fruit of a branch springing out of the dread and hope of Lewis’s own yesteryear. The storyteller in him bequeaths to us the mercies of his childhood.

Other events are presented with the same perspective, even when Lewis leaves it to us to see the Joy-ward effect that a hard circumstance had: his mother’s death, his wandering in the wilderness among “the false gods,” his “dejected and reluctant” acquiescence to Theism. All through Surprised by Joy, Lewis proceeds to demonstrate the good that came to him in times of struggle and suffering.

As he does, he gives me a strong jolt of what I know but don’t always remember: our lives are not the sum total of the events that happen within them.

The Story of Two Lives

On multiple occasions, Lewis takes care to distinguish between the inward state—his thoughts and imaginings—and the outward one. At times, he notes, “the two lives do not seem to influence each other at all” (78). One example is a happy, vividly remembered holiday in Normandy that nevertheless proves to be “of no account; if it could be cut out of my past I should still be almost exactly the man I am” (15).

Many of us have seen this on a larger scale ourselves; we know that a person may pass through beautiful and privileged experiences and remain unchanged, or struggle through a line of tragedies and emerge with indomitable courage and strength (and indeed this is why many believers’ stories captivate us). Life events undoubtedly shape us, but they do not define the direction of our progress; what happens outwardly gives no guarantee of inward change.

For Lewis, World War I was one of the circumstances that highlighted the sharp contrast between the two:

But for the rest, the war—the frights, the cold, the smell of H.E.., the horribly smashed men still moving like half-crushed beetles, the sitting or standing corpses, the landscape of sheer earth without a blade of grass, the boots worn day and night till they seemed to grow to your feet—all this shows rarely and faintly in memory. It is too cut off from the rest of my experience and often seems to have happened to someone else. It is even in a way unimportant. One imaginative moment seems now to matter more than the realities that followed. It was the first bullet I heard—so far from me that it “whined” like a journalist’s or a peacetime poet’s bullet. At that moment there was something not exactly like fear, much less like indifference: a little quavering signal that said, “This is War. This is what Homer wrote about.” (196)

The war, and other situations we might consider momentous, figure very little in this account. In fact, they fade into the background just as an active but unseen presence makes itself felt:

Realism had been abandoned; the New Look was somewhat damaged; and chronological snobbery was seriously shaken. All over the board my pieces were in the most disadvantageous positions. Soon I could no longer cherish even the illusion that the initiative lay with me. My Adversary began to make His final moves. (216)

[T]he day [was] now fast approaching, when I should be forced to take my “philosophy” more seriously than I ever intended. I did not foresee this. I was like a man who has lost “merely a pawn” and never dreams that this (in that state of the game) means mate in a few moves. (222)

The center of Lewis’s story isn’t a tangled web of memories or unfortunate episodes, or other things we might expect a man to describe in his most significant life story; the core is not even solely Lewis himself. Instead, along with him, we follow a series of signposts leading to “the authority that set them up” (238)—to wit, we find Christ.

Our Past as Structure

In a 1956 letter to Dom Bede Griffiths regarding Surprised by Joy, Lewis wrote: “The gradual reading of one’s own life, seeing the pattern emerge, is a great illumination at our age. And partly, I hope, getting freed from the past as past by apprehending it as structure.” He knew that some experiences must be viewed from a distance to become clearer, for the unifying thread to become recognizable—but there is a pattern, and it’s worth tracing.

I’m grateful that he made this observation.

Ours is a world where statistics and studies carry the voice of authority, in which our successes and our miseries seem to be greatly at the mercy of chance. According to its laws, we must follow certain steps to avoid failure as workers, parents, artists—that is, if the One Medical Symptom we’re foolishly dismissing doesn’t cut our lives short by tomorrow morning—while the ground beneath our feet groans under the weight of political turmoil and earth-shattering news cycles each day. Nothing is guaranteed. To view each of our lives as having structure takes either a myopic worldview or a strong dose of denial.

Surprised by Joy offers a different anchor. Lewis’s narrative isn’t simply “another way of looking at things,” or an exercise in finding the silver lining. It reminds me that God’s will for my life has a beginning, an end, and a trajectory in between, and helps me look for His pattern as I read my own life:

This means tremendous joy to you, I know, even though at present you are temporarily harassed by all kinds of trials and temptations. This is no accident—it happens to prove your faith, which is infinitely more valuable than gold, and gold as you know, even though it is ultimately perishable, must be purified by fire. . . . At present you trust Him without being able to see Him, and even now He brings you a joy that words cannot express and which has in it a hint of the glories of Heaven; and all the time you are receiving the result of your faith in Him—the salvation of your own souls. (I Peter 1:6, 8-9; Phillips)

What is being told through our lives is of far greater import than we often suspect, as Lewis attests, and some chapters that seem staggering to us now may fade into the landscape when we look back. Nothing has gone awry that cannot be redeemed, and everything that is permitted to be set in motion will turn out to be for our very great good in the end.

According to the reality that both the Apostle Peter and Lewis spoke from—and they bore their share of heartache—all shall result in joy. A full-blown joy more gorgeous than even that of Lewis’s technical definition: a tremendous, inexpressible, glorious joy.

I consider this as I look back at certain losses that have cut deep, and upon an insidious breed of worry whose finger-marks have bruised my throat. Make no mistake; we are in the thick of things yet, all of us. But we are “passing signposts every few miles,” all pointing Homeward, surrounded by a cloud of witnesses shouting that the road is good and true, that the joy we have tasted and sought in our King will not lead us astray.

It’s enough, dare I say, to give one the hope and courage to keep turning the pages of one’s own life.

[i] C.S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life, (New York: Harcourt Brace & Co., 1955).

Amy Baik Lee is a contributing writer for Cultivating Magazine and the Rabbit Room, a literary member of the Anselm Society Arts Guild, and the author of This Homeward Ache. A lifelong appreciator of stories, she holds an MA in English literature from the University of Virginia and still “does voices” when she reads aloud. She writes at a desk that looks out on a small cottage garden in Colorado, usually surrounded by her husband’s woodworking projects, her two daughters’ creative works, and patient cups of rooibos tea.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

dear Amy, thank you for this lovely review of Lewis’s book! I appreciate that it was more than a review, more like a quiet call to arms–and to hope. We need as much of that kind of exhortation as we can get in this bruised (but beautiful!) world.

Dear Kimberlee, I agree with all my heart on the need for hope and exhortation, and I’m glad this review relayed encouragement to you! The more I read of your work, the more I feel I’ve found a kindred spirit and fellow comrade in just that way. Thank you so much for taking the time to leave this kind note.