The human imagination gazes upon infinite possibilities. In this gaze, it may, if directed upwards, be filled with the vision of God, and so be receptive. Or it may look upon the world and recognize in it the created potential for making, and so actively mold the world. In The Cultivating Imagination, we will explore this nexus. On the one hand, these reflections aim to facilitate our openness to the sweet influence of divine grace raining down upon us. On the other, they are directed at the ways we work the land (of our world, societies, families, and hearts) to create desire paths that allow grace to more effectively water the land. In these two ways, the imagination fulfills the twin duties of love to God and neighbor.

![]()

I sit before a blank page. This is a gift, and a challenge. It is a gift, because, by its blankness, it invites me to make of it what I will. Not all the pages in my life are blank: some are contracts that require me to sign here and here, and initial there, and you’ll not mark anywhere that hasn’t been indicated, thank you very much. Some is manuscript paper, which tells me that I must write music on it, not a sonnet or a drawing of a dragon eating grapefruit. Some are pages filled other people’s thoughts: these I may underline and annotate, but I am not free to edit, to take out and add what I will. And so the blankness of this page is a gift because no one is telling me what I have to make of it.

And yet the blankness of it is also a challenge: “Go on, fill me. Let’s see what you’ve got.” There is something daunting in this challenge, because of the very real possibility that I might not have anything. Every writer knows the feeling of sitting down full of optimism and excitement, then rising in shame while that still all-too-blank page mocks you, saying: “Look! Look at the ‘writer!’ Not even one word: what a disgrace!” I am an experienced writer with all sorts of tricks and tactics, but none of them ever completely removes the possibility that this time I will fail, and that nothing or nothing good will come out.

This is my starting place for thinking about the imagination. The blankness of the page, while it is a kind of emptiness, is not the emptiness of nothingness. When I gaze upon its blankness, I do not gaze into the depths of the non-existence that preceded the first moment of divine creation, when outside of God there was not chaos, but simply nothing at all. In that first moment (whose words we do not know: for He first created the heavens and the earth, and then spoke the first words our race knows: “Let there be light”), God did not create from material, God created material. There was no tense expectation or longing to be because that implies something that can expect or long. There was simply God, and no reason to think anything besides God would ever exist.

This is not the blankness I see before me, because when I look on a blank page, I am looking at a page, which is a thing made to be written or drawn on. The blank page is not yet what it is meant to be: while it remains blank, it is given over to potentiality. Every possibility lies open to it: it could be a grocery list, a love letter, the first page of a great story, or a symphony of heartbreaking beauty. But as long as no one of these possibilities is realized, it remains only something that could be but is not yet. The page comes alive when a maker comes along to define it by selecting that it will hold this particular wonder out of all possible wonders.

This is, then, the blankness of expectation. When I fill the page, I do not do violence to it, I complete it. In writing my little essay on it, I make it specific, I give it determinate form, I make it a piece of culture. Filling in the empty spaces is an act of cultivation.

The work of cultivation requires going from the possible to the actual. This means that one must look at something that is, and see it not only for what it is, but also for what it could be. The faculty that is capable of doing this is the imagination, which specializes in possibility. The imagination starts with things as they really are: for it is a created ability, and can only work within the framework God has given to it. And so it does not deny the world as it is. But it does not stop there: it probes deeper, to see what the world could be, and in so doing, looks under the curtain of appearance to discover the truth God hid there for it to find at the foundation of the world.

In the early days of the Church, when the faith was but a girl of 7 or 8, in the eastern parts of the Roman empire monks began to go out into the wilderness to escape the decadence of the cities and to focus on an extreme form of the life of prayer. They sought out desolate places, where they would be free of every temptation to luxury. But then a strange thing happened: they had to dig wells to have water to live, and they would work the land for food. Eventually they began to cultivate beauty in their spaces, in order that the inner beauty of holiness might find an outward expression. They built beautiful chapels and decorated them with holy images. In the end, the desolate place was turned into an oasis, a place of beauty and fruitfulness. When travelers heard about it, they began to divert their paths to pass by the monasteries, so that they might behold the beauty, but also to find food and water on their long journey. And so the roads shifted and began to go past the monasteries, and communities grew up, and the monks who had retreated from the world found themselves serving their fellow men, who had been drawn in by beauty.

This is an image of what the imagination suspended by grace can do to the world around the Christian. There are many desolate places in the world, even today: some of them geographical and some of them metaphorical. Indeed, in the wake of modernism and industrialization, often the most developed places are the most desolate: for man was not made for hermetic seals and antiseptic cleanliness, and our hearts will never forget the open spaces and the simple magic of the color green. And as our hearts grow sick with unsatisfied longing, they will turn to the only medicine that can cure wounded hearts: the spiritual. If that is not available to us (because we have shut it out in disbelief and rebellion), then a second, greater desolation arises: a desolation of the heart. Out of this desolation we pour lamentations, and they flow into all of our making, and so this art becomes a cry of lonely despair. This art can create a culture of desolation, which in turn teaches new children born into this wilderness that all that awaits them is disappointment and pain. This sense grows until the springs of wonder dry up in their hearts and they settle down to a life of resignation, or take their leave of the world early in a (to those of us left behind) perplexing, heart-rending act of rejection.

The desolation of the world is all too common a companion for us these days; but we need to look to the early monks for the clue to healing it. They teach us that perhaps the reason the feet of those who bring good news are blessed [1] is because their footsteps irrigate the land. It is the very work of holiness to transform the desolate into the fruitful and beautiful. This was the unexpected discovery the monks made: that asceticism can be a way of opening the door to greater beauty. Of course they believed this to be true spiritually, or they would not have gone out; but they did not seem to have known that it would also be true physically. They were impatient with the physical, which is so often the source of temptation and trial; but the faith of Jesus Christ is all about embodying.

And so while the worldly who go out into the desert learn to be spiritual, the ascetics who went out into the desert learned to love the physical.

This is the necessary consequence of Incarnation. When Christ became human, He made the unfruitful world fruitful. Likewise, when we bring the water of spiritual truth to a world without grace, we create meaning, restoring to things their created potential. The Christian imagination, taking both the works of God and the works of human culture as material, can irrigate the desolations of culture and human hearts and minds, restoring their fruitfulness and rendering them beautiful. In this way we imitate the holy self-emptying of Christ, which laid aside equality with God to assume lowliness so that we might be made worthy of God. [2] The natural end of this is exaltation: for the one who lifts up will himself be lifted up to the heavens and given a home in the household of God.

If we do not bring imagination to bear on our lives, we will continue to live in arid places. This is possible, even for the Christian, but it is a special gift and calling: after all, the hermit is rarer than the monk.

![]()

[1] “How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of him who brings good news, who publishes peace, who brings good news of happiness, who publishes salvation, who says to Zion, ‘Your God reigns’” (Isaiah 52:7, ESV).

[2] Philippians 2:5-11, ESV

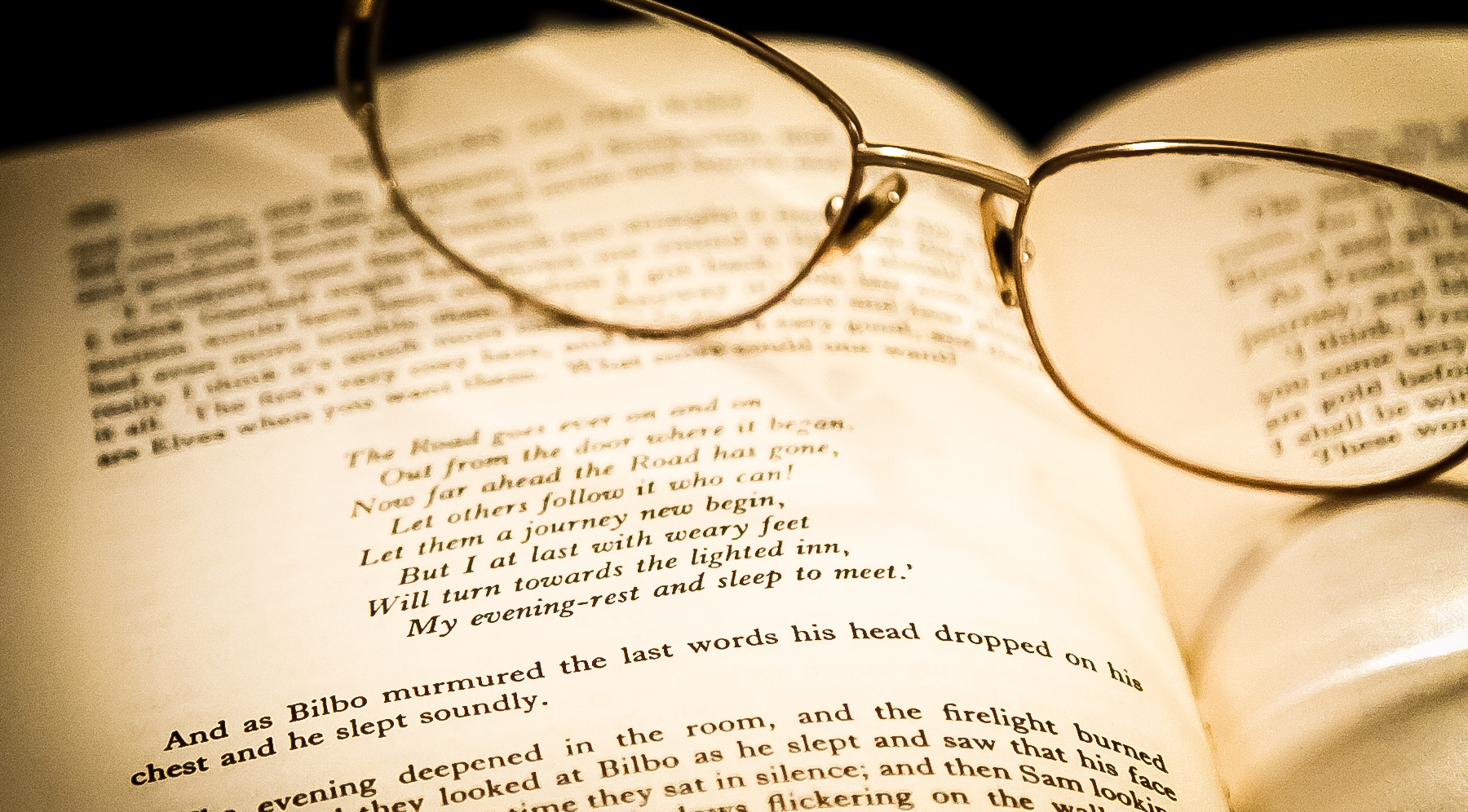

The featured image, “The Road Goes Ever On,” is courtesy of Lancia E. Smith and is used with her glad permission for Cultivating.

Junius Johnson is a scholar in the fields of historical and philosophical theology and has published four books in those areas. He is also a lover of story, passionate about beauty and the imagination, a seeker of wonder, a musician, and a deeply flawed sinner daily leaning on the grace of God in Christ. A lover of the Middle Ages, he especially loves to be transported to other worlds via fantasy, science fiction, and young adult literature. He teaches online enrichment courses for both children and adults in literature, theology, and Latin through Junius Johnson Academics.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

Add a comment

0 Comments