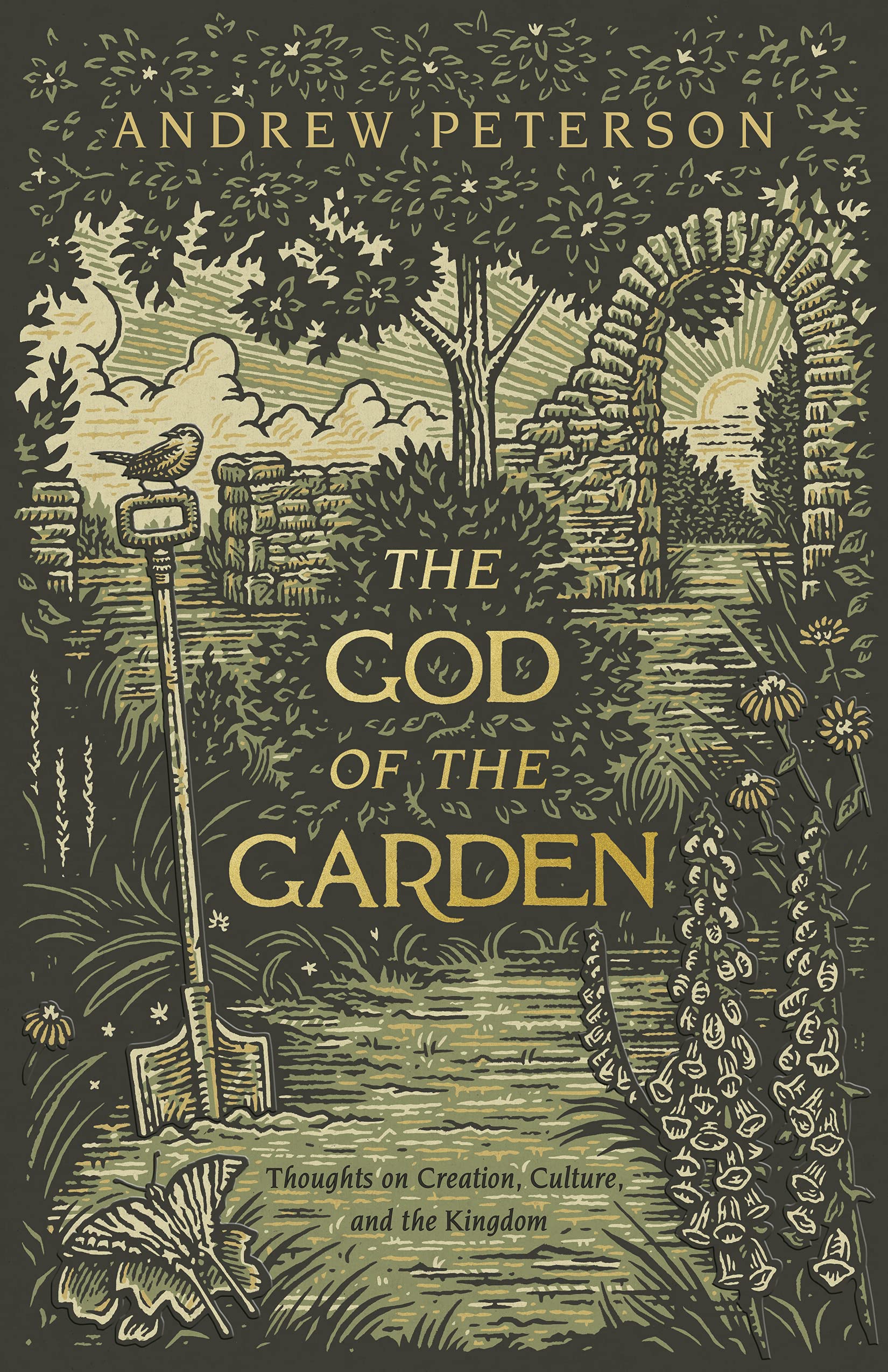

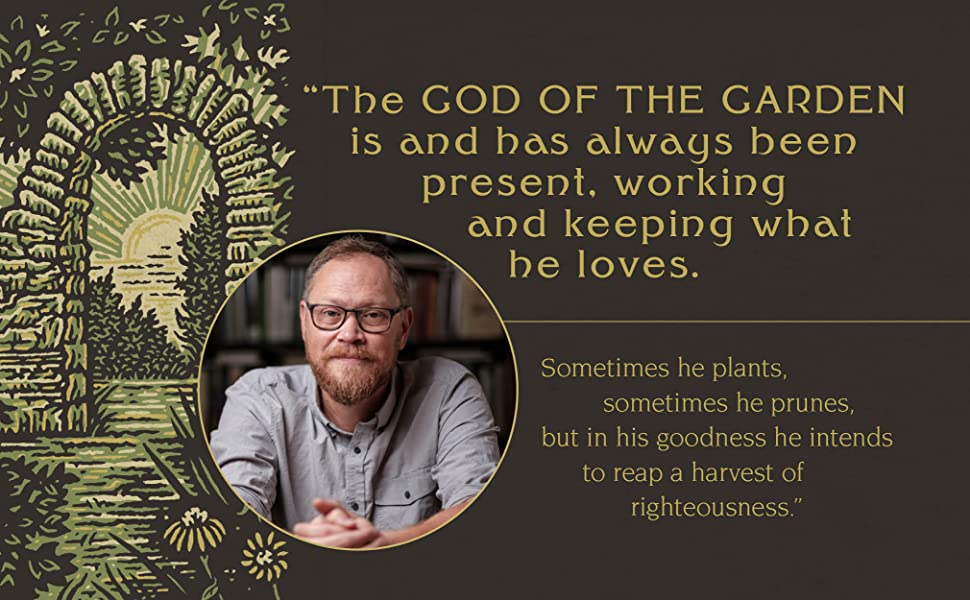

Andrew Peterson is a beloved name to readers of Cultivating. A man of many skills, Andrew is a singer-songwriter, author, illustrator, gardener, beekeeper…. He is founder of the widely loved community of the Rabbit Room, and the magnificent The Behold the Lamb of God tour. Andrew is known for his “everyman” style of presenting in all his genres. A superb storyteller, he invites us into the great Story in which we each play a part, and in this interview Andrew gives us an inside glimpse into his newest book – The God of the Garden – and offers Cultivating readers a benediction to go forth and fulfill our calling to cultivate the worlds given us. It is our privilege and honour to share this conversation with Andrew Peterson with you!

![]()

Of trees and gardens

LES: The God of the Garden follows Adorning the Dark. Because they both have a consistent voice and style, together they make a beautifully paired set of memoir, reflection, and encouragement. But while Adorning the Dark is about creativity and community, The God of the Garden is focused on a private landscape and your connection to the physical world. What sparked the idea for this book using trees at touch points and the garden as an anchor for your life?

AP: In 2020 when I agreed to write this book, there was no clear sense of what it was supposed to be about. After a few weeks of kicking around ideas and meeting with a group of fellow authors, I realized two things. First, I was reveling in being home. Our little property here demands a lot of work, and because I tour so much that work comes in fits and starts. It’s hard to describe but I experience an almost physical ache when I’m gone on the Resurrection Letters tour in the spring when I know that the property itself is resurrecting and there’s so much to see and do. There’s a heap of joyful labor waiting to be done but I’m only home for a few days at a time, which gives the work a frantic edge; I’m trying to squeeze in as much as I can before getting on the bus for the next run of concerts. But last year because of COVID, the urgency was gone. I woke up every day with a sense of purpose and gladness, striking out early in the dewy grass to tend to things slowly, steadily, the way they were meant to be tended to. I didn’t know if it would ever happen again, so I was giddy and grateful.

Second, I looked at the stack of books I’d been reading. For some reason I was gobbling up books about trees. But also books about the land. Books about farming and community and even infrastructure. I don’t know about you, but I typically latch onto some idea and binge read for a year or two. This year it was all manner of agrarian concerns, and I was reading them through the lens of theology—specifically our call to care for God’s creation (including people, of course) as priests of the New Creation. I mentioned the idea to our little writer’s group and they affirmed it at least as a starting point for this project. Then I heard the Bible Project’s podcast series on trees in the Bible, and I was off to the races.

Establishing poetic anchor

LES: You use excerpts of William Wordworth’s “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” for the opening of each chapter of The God of the Garden. Those excerpts anchor the chapter and give a framing to what is coming in it. What is the story behind that choice? Did you choose these before you wrote each chapter, or did you add them afterward?

AP: A few years ago Malcolm Guite gave me a copy of Mariner, his life of Coleridge. I had never dug into the Romantics, and to be honest I’m still a rookie when it comes to poetry in general. It wasn’t until about ten years ago that I started reading it in earnest. Wordsworth and Coleridge were masters, game-changers of their time, but I was really interested in Guite’s account of their Christianity, which was at times overt in their work. This is a side note, but it struck me that my songwriting hero Rich Mullins was writing in the Romantic tradition, with a strong focus on God, childhood, and transcendence in nature. If I were an academic I’d be tempted to write a thesis on that idea. Anyway, I picked up a pocket edition of Wordsworth’s poems and read through his “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Reflections of Early Childhood” a few times. I loved it. Meanwhile, I was deep in the process of writing about my own childhood—my relationship to trees specifically, but to nature in general—when I realized that the poem resonated eerily with the themes of The God of the Garden. When the book was finished I thought it would be cool to open with a few lines from Wordsworth, but then I realized that each chapter connected in some way to stanzas in the poem. It was the perfect framework.

Of shadows and transparency

LES: Over many years you have been very generous, Andrew, in sharing about your experiences with deep depression. It is a service and a kindness that is deeply needed by many. How has the act of transparency shaped your experience with it? Has writing this book helped you mend some of the internal shadows you’ve shared about?

AP: I still feel a little sheepish talking about depression, because it’s such a complex experience. It’s different for everybody, and it’s too big a thing to be contained by that one little word. I’ve dealt with “melancholia” off and on for most of my life, but whatever happened several years ago was deeper, more sustained, and more painful. It has also borne more fruit. That metaphor is intentional, because gardening is one thing the Lord used to lift me out of the pit. I’ve written songs about it, and talked about that idea from the stage, but I wanted to get it down in prose and explore a bit more of what was really going on, what it really felt like, and what it feels like now to look back and see the many ways Jesus made himself known to me. The writing of this book unearthed a lot that I had either forgotten or chosen to ignore, so the final chapters were cathartic, yes. This book is yet another field I was given to plough, and one where God revealed his presence and upwelling kindness yet again.

![]()

“The better part of the Chapter House is made of trees. The ceiling, the floor, the front door, the bookshelves, the drawing table, the mantel, and the pine frame were once living trees. That means something. What also makes a house meaningful is the stories that it houses.”

Chapter House

LES: For years you wrote in your house late at night, or in cafes and assorted other places. Now you have a beautiful place at The Warren called the Chapter House, a lovely kind of cabin where you go to write. In England small buildings dedicated to sheltering a writer at work are called writer’s huts. S.D. Smith’s is called The Forge. Malcolm Guite’s is called The Temple of Peace. The names each are so telling. How did you come to name yours Chapter House? Is there a sense in this place of something coming full circle, a kind of ‘further up and further in’? Has it changed your sense of identity as a writer?

AP: A proper chapter house is “a building or room that is part of a cathedral, monastery or collegiate church in which meetings are held.” I liked the writerly play on the name. When I first built this place it ended up being a bit bigger than I intended. I wanted it to feel like a cross between a chapel and a pub, and I think we achieved that, what with the vaulted ceilings and stained glass paired with the musty smell of old books and pipe smoke. But at first it felt a bit lonely in here, not as snug as I imagined. Then I started having friends over, whether for pipe nights or Bible studies or book clubs, and the size made a lot more sense. The name did, too, because it’s better suited for rowdy raconteurs and earnest conversation than just banging away at a computer or reading alone. That’s not to say I don’t love to be out here by myself—just that it’s at its best when it’s cold out, there’s a fire in the hearth, and a group of friends is gathered. I just read in C. S. Lewis’s letters, “Is any pleasure on earth as great as a circle of Christian friends by a good fire?” I’d have to agree.

A lot of writers have this romantic idea that if they only had a writer’s hut they’d crank out no end of glorious prose, but the truth is more complicated. I haven’t found it to be any easier to do the gritty work of writing.

As I said in Adorning the Dark, there’s no magical formula. It always comes down to the work and the will, not to mention a whole heaping of grace. And yet! And yet there’s something to be said for seasoning a place with stories. Here’s what I’m trying to say: the stories written in here are a distant second to the stories lived here. There have been long and painfully healing conversations here; I’ve laughed so hard with friends that I dropped my pipe and ashes scattered across the rug; I’ve sat and listened to sages as they reveled in the beauty of scripture; we’ve cooked up some big dreams and mourned the death of others; I’ve even gotten in some arguments here; I’ve forgiven here—I’ve been forgiven here. It’s not the stories written as much as the stories played out that hallow this space. It’s no use trying to be a writer if you have no real life to write about.

![]()

“I saw the gleams of water through the trees and knew again that I wasn’t alone—not isolated at all, but present in the mystery of time to Wordsworth himself as I gazed at the grove and the lake and the unaltered shape of the surrounding ridges. Some of these very trees had already been sending out their spring leaves two centuries ago as Wordsworth and Coleridge ambled along the contours of this same shoreline. Those trees and that clear lake assured me that, in the overlay of time and particularity, we are surrounded by a cloud of witnesses to God’s abiding presence. We are here and gone, but poems last—sometimes even longer than trees. We can walk among words as surely as we walk among the ancient groves.”

Andrew Peterson, The God of the Garden

![]()

Walking among words

LES: Andrew, in our earlier interview for Adorning the Dark, we touched on the fact that poet Malcolm Guite keeps company with departed poets through the way he reads and interacts with their surviving words. Alan Jacobs echoes this idea in his brilliant book Breaking Bread with the Dead. He says of the Roman poet Horace that, “The past became a companion to him in what otherwise might have felt an exile….” Here you capture this notion afresh about keeping company with those who have gone on before us, but you expand it with the inclusion of keeping company with trees and the particularity of place. How does this enlarged awareness of time, place, and presence inform your sense of the Kingdom of Heaven?

AP: I’m fascinated by the idea of time. We’re bound to it, frustrated by the decline of these bodies that were meant to live forever. We tend to think of time as an enemy, something we’re always working against, with the specter of our eventual deaths haunting the road ahead. But in the New Creation, time will no longer feel like a curse but a blessing. We’ll plant trees knowing we’ll be around in 800 years when they’re enormous. I love that thought. Gardening trains us for it, because we begin thinking in terms of seasons and years, not just hours and days, like when Frederick Olmsted designed Central Park to come into its own in a hundred years, knowing he wouldn’t be around to see it. I’ve also heard theologians suggest that in eternity we’ll be beyond time—I think Lewis played with this idea—but I disagree. Music, for example, doesn’t work without time. Stories don’t, either. How could there be a song in the New Creation if there weren’t successive notes, or poems without a progression of thought ending with a turn of phrase and a catch of the breath? I see nothing in scripture to suggest that time will be irrelevant or supplanted but rather that time, as I said, will no longer be an enemy. It’s like what I mentioned about COVID giving me the freedom to be home to work the property without the urgency of knowing I had to leave in a few days. It reminds me of Jesus talking about the fullness of time. We experience it as fleeting, but we will know it as he knows it now: full, abundant, complete. When you have an overlay of time and place, there’s a mysterious sense of connection to the past that reframes the present and awakens our awareness of the future—time in its fullness. The place is still, but our experience of it is not, which is to say that we have arrived there from elsewhere, and will be going hence. Place is static, and time is kinetic. At the intersection of the two there’s a harmony, a rhyme, a marriage that makes a oneness of the parts. That’s one reason trees are so marvelous. They’re rooted to a place, but they’re living witnesses to time. Stories, in that sense, are like trees. We plant them in a place, and they become witnesses for those who come after. I’m not saying any of this makes sense (ha!), but it’s what I think about when I’m in a storied place.

![]()

“And now, when the sky is heavy and gray and the rain keeps falling?

I rejoice. I’ve planted seeds, you see, and my feelings about rain have changed.

Something good is coming. Every spring, it’s inevitable.”

Andrew Peterson, The God of the Garden

![]()

The importance of planting seeds

LES: You share a beautiful little poem from Luci Shaw called “Forecast” that goes like this:

Planting seeds

Inevitably

Changes my feelings

About rain

Would you talk with us a little more about the importance of planting seeds and what that means?

AP: As I wrote in the book, gardening is, fundamentally, an act of hope. It is a present act that embodies an expectation of the future. When you’re in a depression, the great lie is that there’s no end to it. “This,” we think, “is all there will ever be.” But God intends good for his children, and for the world. It’s one of the clearest pictures to me of what Wendell Berry calls practicing resurrection, because we aren’t just planting seeds in the dirt; we’re planting seeds in our imaginations, making room for the possibility not just that there is beauty coming, but the hope that we’ll be around to see it.

Grief and the garden

LES: Your chapter titled, “We Shall Be Led in Peace” is a section of the book I resonated with personally around the issues of grief and the consolation of the garden. Your story about the janitor’s closet experience hits especially close to home as I have had a very similar experience in a hospital closet. For me, it was years before I began to understand the truth of what you describe here:

“Could it be that when you’re deep in the dark cave, it’s not because he doesn’t love you, but because he does? I wasn’t angry at the earth when I wounded it. Nor was I killing the seed when I buried it. I was giving it a chance to be born again.”

Considering the mysterious possibility that God allows the experience of grief because He loves you and me, do you sense, Andrew, that you have been given a magnitude of grace and knowing that you could not have apart from the grief?

AP: It’s hard to reconcile it when you’re in the cave, but I believe so, yes. Grief, for me, was and is a kind of pruning, a shaping of the heart that can happen in no other way. It is a giving over of oneself to pain because it’s the only way to heal, entrusting the flourishing of your heart to the Gardener. If he’s good, and he says that the best way to bear fruit is to be pruned, then we have to let him. It’s terrifying, but gardening teaches us that it’s true.

A deeper language

LES: I also found consolation in two gardens, both very different from each other, each fitting to the season of our life at the time. Much as you describe for “Mr. Joey’s dad” and for yourself, I experienced that same astonishing wonder of healing that is found only in the growing and tending of beauty in the earth.

“In a literal sense, God turned my grief into a garden…for me each seedling that sprouted was its own kindness, its own obedience to Christ’s command to come forth from the grave.”

For the consolation of grief, a deeper language than ours is required. It is the language of abiding things – things that outlive us and yet invite us to keep company with them – that speaks to the agelessness of grief. Trees and gardens speak this deeper language and, if we pay any attention to them, in keeping company with them we can learn to understand this language.

In this same chapter of The God of the Garden, you describe the gift of being given a 30-year garden design plan by your friend Julie. Does that long-view of the garden give you a kind of map to navigate through the seasons of grief like a pilgrim heading homeward?

AP: Yes, it’s like the moment we submit to Christ’s lordship we receive a garden plan. He shows what he means to make of us and we agree. In that moment the future garden is as real as the mess we see in front of us, but time requires us—no, allows us—to participate with him in its making. There’s great joy, a lot of hard work, seasons of mud and seasons of plenty, but it’s all according to his incarnating plan and by his grace and good pleasure. It’s just an analogy, but it’s a good one.

![]()

Naming the Word

LES: In your chapter XI, A STONE’S THROW FROM JERUSALEM, you recount your experience visiting the Holy Land and to Jerusalem. In it you describe Jesus as the Root, the Seed, the True Vine, the Tree of Life. Then later in the chapter you write,

“Love conquers slowly, like seedlings pushing through mud. It is only in hindsight that we see the broad, upwelling green of springtime as an explosion of life. Look back! He was always coming, always already there—

From you comes the theme of my praise in the great assembly;

before those who fear you I will fulfill my vows.

The poor will eat and be satisfied;

those who seek the Lord will praise him—

may your hearts live forever!

—and He was always going to be in the end, Lord of the Night, King of the Morning, Gardener of Oaks, Germinator, Tiller of the Heart’s Soil, Reaper of the Glad Harvest.”

![]()

There is such power in the way that you named and called Him. You have named Him here as the Alpha and Omega of Cultivators. Seeing Him with these titles, does it change what you think of Him and yourself from when you first met Him?

AP: That’s a good question. I think when I first collided with Jesus on the road to Damascus (which was really the road to self-destruction and a misguided sense of what life was for) I assumed things would change in an instant. What I found, and what I still find today, is that his work is achingly slow. I’m still beset by so many of the same sins, the same tendencies, the same general selfishness that I thought would vanish overnight. But he knows what he’s doing. He’s engaged in the shaping of our hearts, not just the saving of them. The moment of submission is not merely the end of a story (and it is that, to be sure) but the beginning of a better one. And stories take time. The question is always, “Do you trust him?” If that means rooting out weeds, so be it. If it means pruning back the vine, we have to learn to trust the master of the vineyard. I was talking to a young writer the other day about her first book, and I said she needs to think of it as her first book of twenty. If she wants to be a good writer, she has to be in it for the long haul, releasing herself of the expectation that she’ll figure it out in one go. The slow becoming is good and necessary and painful, and is a better thing than overnight success (whatever that means). I would tell the young Andrew to be patient, to think of this as the beginning of a long journey into knowing what it really means to be loved by Jesus.

Marriage of nature and culture

LES: In PLACES AND NO-PLACES you venture into more difficult terrain and begin to address the issues of suburban developments that decimate the natural surroundings upon they are so often built.

“Few things are more wonderful to me than a graceful integration of nature and culture, which is essentially what a garden is—and few things are less wonderful to me than the razing of a forest to plaster yet another soulless subdivision onto yet another corner of the land.

… But if we integrated the loveliness of creation with the flourishing of human culture would we be that much closer to a vision of the New Creation? I think we would. The story of redemption ends with a tree and a river in a city. In other words, the New Jerusalem will be not just a marriage of Heaven and Earth, but a marriage of nature and culture. …

Let the American dream be supplanted by one of the Kingdom, where every square inch of the earth belongs to Jesus and we shape our sidewalks and streets, our homes, farms, and restaurants accordingly.”

From your perspective, are the ways that we can participate in this effort even if we do not own land or know any land developers, city planners, and or landscape designers? And if we choose to supplant the American dream in ourselves and replace it with the dream of the Kingdom, how do we best go about the business of hallowing the ground where we dwell?

AP: This is tricky, and I don’t have any easy answers. But it starts with a change of thinking. If Jesus is the reigning king of heaven and earth, then we’re obligated to participate in the welcoming of God’s kingdom on earth as it is in heaven. Right now. N. T. Wright urges us in Surprised by Hope to get involved in local government, city planning, shaping things to reflect our best guess of what the kingdom of God will look like in its fullness. That means justice matters. Community matters. Proper love of neighbor—across lines of race and class and education—matters. Caring for the world God so loves matters. No country is doing it perfectly, but for the purposes of this book, America in general is barreling forward in a way that values money over community, beauty, and human flourishing. It’s what Wendell Berry has been writing about for sixty years. It’s also what the glut of apocalyptic films suggests is on our minds, whether we admit it or not. We all seem to have a sense of impending doom, but we’re too distracted or overwhelmed to do anything substantial about it.

That’s why I suggest in the book that we start small, locally, with the proper stewardship of place as a way to love our neighbors and those who come after us for the sake of the Kingdom.

Practicing resurrection

LES: From the varied threads of theme woven together in this book, two phrases particularly linger with me. From FOOTPATHS, comes: “So what is there to do but begin the patient work of hallowing what we have?” And from EPILOGUE, “patiently practicing resurrection.”

They both involve patience. Every true Cultivator holds patience and endurance as core characteristics, yet few of us are born patient or enduring. They are character traits developed and refined over time – often through trial. They are practiced and learned. Neither of them is much popular in our times because they both come through trial, suffering, and extended disappointment. There is no quick acquisition of either. What do you suggest for leaning into day-to-day rhythms for deepening our roots?

AP: I think everyone (including me) should spend less time in front of screens and more time interacting with the given world of creation. The other day there was a glorious rainbow right over our neighborhood. Jamie and I were on the way to grab dinner and we pulled the car over to gawk. On either side of the street that leads through our neighborhood were dozens of homes and lawns and garages, and I didn’t see a single human being. I wanted to bang on doors and tell everybody to step outside for a few minutes. I’m sure I’ve missed plenty of natural wonders because I was glued to the screen, but that moment stuck with me as a stark reminder that most people in our part of the world often miss the glory that’s right outside their windows. I know this sounds simplistic, but I honestly believe that one good way to start is a re-engagement with creation, which would lead to a re-engagement with other people. This is complicated stuff, because there are historical (and sinful) reasons why our communities look and feel the way they do, and undoing that takes time and work and imagination. But a Christian vision of the New Creation, of the glorious “why” of it all, and of what people are for, is a good place to start.

![]()

“The temple of God is the place where earth and heaven meet. This is true of Jesus, who called himself the temple—and by the indwelling of his Holy Spirit, it is now true of us. Every child of God rambling around the neighborhood is a temple, a confluence of earth and heaven, a tree whose earth-bound roots drink from the river of God and whose branches breathe his heavens. A wedding day is coming when the New Jerusalem will descend, we’ll see the face of our True King, and we will at last know the fullness of time and place and, above all, love. Let us live in the surety of that love by working and keeping what is within our reach, for the good of his creation and the glory of his name.

Dig deep. Branch out. Bear fruit.”

![]()

The call to cultivate

LES: Andrew, the lines you’ve written in the quote above so beautifully capture what I could easily say is the call to cultivate. It is the call to abide, grow, and flourish in the places where we dwell and to bear witness to The Lord’s coming glory while we live on earth.

Would you offer us a benediction in our call to cultivate that we may flourish in digging deep, branching out, and bearing fruit?

AP: Don’t try to change the world. Just love it. Love it like Jesus does. Love the people in it, the trees draping their branches over the roads, the turning of the seasons, and the sound of laughter. If God’s people joyfully lived out the good news—not just that Jesus died for us and rose again, but also the news about why—then I believe the world will change and we will too. He came that we would have life, and have it to the full, and he’s promised that we would be priests who would work and keep this garden, which will be his his temple and our home. The most beautiful part of the promise, to me, is that he’s going to dwell with us again. Here. He will be our God and we will be his people. And this place—this place, which he called good and very good—will be made holy by the Lord of Time, the Lord of the Sabbath, the Lord of Creation. We shall go out with joy into the fields—these fields, made new.

![]()

The featured image of Andrew Peterson is courtesy and (c) of Eric Brown.

The gorgeous cover for The God of the Garden, as with the cover for Adorning the Dark, is by illustrator Stephen Crotts.

Lancia E. Smith is an author, photographer, business owner, and publisher. She is the founder and Executive Director of Cultivating Oaks Press, LLC, Cultivating Magazine, and its fellowship of writers and makers. She has been honoured to serve in executive management, church leadership, school boards, and Art & Faith organizations throughout her career.

Now empty-nesters, Lancia & her husband Peter make their home in the Black Forest of Colorado, keeping company with 200 Ponderosa Pine trees, a herd of mule deer, an ever expanding library, and two beautiful black cats. Lancia loves land reclamation, website and print design, beautiful typography, road trips, being read aloud to by Peter, and cherishes the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and George MacDonald. She lives with daily wonder of the mercies of the Triune God and in constant gratitude for the beloved company of Cultivators.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

Any interview with Andrew would be good, interesting, and edifying, but you, Lancia, know how to ask just the right questions to make it epic. Thank you.

June, I am am so honoured by your kind words. Thank you! I do labour over the interviews and am grateful that they serve more than just idle questions! Many blessings to you. 🙂

As usual, a wonderful interview to sit with and read again, Lancia! I look so forward to these interviews in each new season. Your thoughtful questions always help me see what can happen when we pay attention to people and their words & stories. They seem to become so at home in you that you can both honor the writer and encourage the reader with your questions. Such a gift to read & learn here!

oh, Emily, what a gift you are! Thank you for your own thoughtful attention, and your encouragement. May your blessings be many!