“Every person is an artist. The whole of life is a creative act.”

~Ranald Macaulay and Jerram Barrs, Being Human

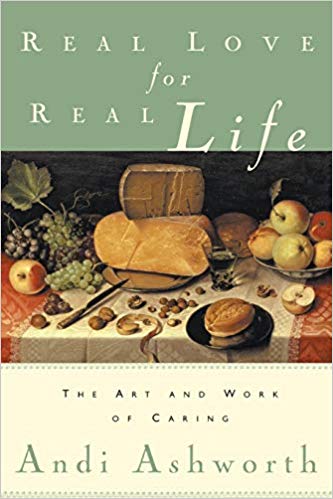

This quote marks the beginning of Andi Ashworth’s remarkable book Real Love for Real Life: The Art and Work of Caring, a work that was instrumental in changing my mindset regarding the role caretaking plays in the creative life.

What does it even mean to flourish as a creative person—as a writer, an artist, or a maker—in the midst of our responsibilities as a parent or as a caretaker to our own parents?

After all, flourishing isn’t how I would describe my initial experience of caretaking. For the first year of my daughter’s life, I often felt trapped in “survival mode” and would have had no idea how to answer this question. It felt like my vocations as a mother and as a writer were at odds, leaving me frustrated, overwhelmed, and exhausted (I’m sure there are plenty of creative women out there who can relate). But then I had a minor revelation, one that had a significant impact on how I view the creative life.

It started with a simple question:

Why?

Why is it so important that I not only be a writer, but a published writer?

Why do I feel this unbearable urge to think deeply about the world and to then express those ideas through words and story?

Why do I require that my paid, pay-the-bills work also make use of my creativity?

Why do I often feel angry and resentful toward those I love when their demands make “writing time” seem nearly impossible?

It turned out my “why” went deeper than personal ambition or even the desire to share my writing in ways that might benefit others. Yet if I’m honest, I also realized that much of the time—Lord have mercy—the sole motive behind my creative impulses isn’t building up the Kingdom of God through the written world (though it would be great if human motivation could be so pure and straightforward).

Asking this series of “whys” helped me understand that what I desired from my writing was a life where I had the freedom, flexibility, and emotional energy to use my creative gifts in ways that allowed me to cultivate both meaningful relationships and memories.

I realized that my desire to write couldn’t be limited to the actual words on the page—I longed for the beauty I experienced through the act of creation to spill over into my everyday life.

I wanted my vocations as a mother and as an artist to converge in ways that allowed one to feed and inform the other.

In other words, I longed to flourish as whole human person with creative capacity, not a divided, compartmentalized list of responsibilities, identities, and roles.

I believe that many of us who feel called to the arts know intuitively that we are drawn to creative pursuits not only because beauty gives us a foretaste of eternity, but because they allow us to touch the essence of life itself—all that is most meaningful in the present moment.

Creative acts have the capacity to be, in the language of T.S. Eliot, “timeless moments”—spaces where earth and eternity meet.

This truth is at the heart of Ashworth’s message as she explains how much of the wisdom we might apply to our lives as caregivers—whether as parents or in another capacity—also applies to our vocations as sub-creators who seek to partner with the Holy Spirit.

For example, Ashworth’s observation that “Things in life that are meaningful take time and effort to produce” is as true for the artist as it is for raising children, not to mention a much-needed reminder in our world of quick fixes and instant entertainment.

Yet one unique aspect of Real Love for Real Life is the fact that Ashworth doesn’t claim it’s solely up to women to make their families into Instagram-worthy works of art—little microcosms of all that is true, good, and beautiful. While this holistic ideal may be especially appealing to women with a more creative bent, it can also create a laundry list of expectations that become stifling, not to mention impossible to live up to for long.

Ashworth reminds us that creativity and caring for others are key ingredients to a flourishing human life, meaning they’re something all people are called to. Just as many women long for meaningful, creative work that extends their identity beyond mothering, men also benefit from the relational bonds and sense of purpose created when they embrace caretaking as a part of how they are made in God’s image.

“The assumption is often made that mothers should do the lion’s share of the child rearing, and yet this idea is completely contrary to Scripture,” Ashworth explains. “The Bible gives us a clear picture of intimate, long-term care from both parents…Hope for reversing today’s destructive trends lies in understanding the supreme importance of the artwork of raising babies to adulthood. It also centers on the joint responsibility of mothers and fathers to raise children and manage their homes.”

Andi goes on to highlight the diverse and creative ways many husbands and wives are (re)structuring their work and family lives so that both men and women get to experience the blessing of caretaking and creative work—recent developments that will likely become increasingly common as our society’s notion of “work” looks less and less like 20+ years at a single 9-5 career outside the home.

The notion that divorcing our work (creative or otherwise) from our lives as caretakers is dehumanizing for both women and men is an important reminder, since it points to the reality, “the why,” behind all of God’s creative acts starting with Genesis. Acts that are always in the service of relationships.

In the service of love.

“When we care, we reflect the artistry of God,” writes Ashworth. “When we express his creativity, his love, his compassion, we draw others to him—and we ourselves come to a deeper understanding of the artists he has created us to be.”

That’s it.

The “why” we might all aspire to, even if our very human intentions tend to be more mixed.

If you’re a woman who longs to integrate your experience of motherhood, of caretaking, with your art, I invite you to join a community of creative mamas who are seeking to do just that.

May we all come to a deeper understanding of the artists He has created us to be.

The featured image of the espalier in the enclosed garden is taken in England’s Lake District at the home of William Wordsworth. It is (c) Lancia E. Smith and used with permission for The Cultivating Project.

Ashlee Cowles is the author of Beneath Wandering Stars and Below Northern Lights. She writes about motherhood as creative magic at The Most Creative Thing.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

Thank you Ashlee, and thank you Lancia.

Was it Lewis who said that God shouts in our pain? Not sure if he meant that the pain is God’s shout or that He yells when we are in pain, (as pain can stop our spiritual ears). Either way, your article was a megaphone from God’s mouth to my heart today. My very current and painful struggle is between my desire for unrestricted space and time to write and my role as care-giver to my wheelchair-bound Mom. His answer to my guilty heart was as loving as it was clear—the two can and likely ought to co-operate in the honest creative’s life. Thank you, again.

Denise, you are truly welcome. I am so glad that Ashlee’s beautiful work can help you bridge those worlds of loving and bring a sense of balance. I know that struggle all too well and know that there is a peace that comes as we do all the things God calls us to. Sometimes we write with words. Sometimes we write with love. And yes, it was Lewis who said the Lord uses our pain as a megaphone to get our attention. I think Lewis later may have wanted to amend that, but it is often true. You are in my prayers. You can rest assured that however much the struggle seems unending, it will end because He promised that the He will finish the good work that He began in you. If you have never read Lewis’s essay Learning in War-Time, I encourage you to give yourself a gift of reading it. It is in his collection titled after his famous sermon, The Weight of Glory.