The space between joy and sorrow is its own room in our hearts.

Joy. That mysterious movement of longing in the spirit. That feeling which no words can adequately speak of but is somehow wrapped up in delight, beauty, and hope.

And sorrow. More than the pain of a scratched knee, this is suffering that cuts deep into the spirit. Something that opens a void inside. Here hope seems a stranger.

In the opening chapters of Luke, as the story of the Messiah’s birth unfolds, we witness Mary submitting to a hard, life-altering call. She learns she is chosen to carry and mother the Son of God; her community, including her betrothed, learns of her pregnancy; and later she and her husband travel to a faraway town to follow Rome’s edict to be counted in a census. There she gives birth in a stable. Afterward, shepherds come to her and share their story of an angel bringing a message of a baby wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in a manger. It is written that after they left to tell the rest of the town their news, Mary “treasured up all these things, pondering them in her heart.”

The word “treasure” is used in many of the translations of this verse. In my imagination, she has taken these words and put them in her heart, along with other memories connected to the foretelling of the birth of her son—as if putting keepsakes in a special box. She placed the astonishment of the shepherds next to Joseph’s dream, alongside of her cousin Elizabeth’s baby jumping in her womb, and on top of God’s message she received from the angel Gabriel. These would be her treasures, ones she could take out, look at, and think about. These treasures could not be stolen from her by a thief at night, nor be destroyed by rust.

The second chapter of Luke tells of Mary and Joseph with baby Jesus in Jerusalem in the temple. An old man Simeon approaches them, and while he holds the baby, declares Jesus would cause the falling and rising of many in Israel, and that a sword would pierce Mary’s own soul. Mary hears of a future pain connected with this little boy who has been the source of much to treasure.

![]()

Mary’s joy and Mary’s sorrow. Her treasure. Her sword.

And the space between.

Where is Mary’s help—our help—in living in the space between the joy and the sorrow, the treasure and the sword?

The American painter Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937) might offer to us a glimpse at the answer. Tanner used his brush and oil paints to create paintings of Biblical narratives to portray the power of grace—grace found in a moment— to reveal God giving the gift of transformation to live between the treasure and the sword. As the art historian James Romaine asserts regarding Tanner’s paintings of Mary, the artist sought to portray the visual power of grace and the power of its impact to highlight how Mary had been transformed by faith. [1]

The Annunciation, found in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is Tanner’s most famous biblical narrative. This painting was the beginning of Tanner’s vision to paint stories of Scripture with integrity. Completed in 1898 after his trip in the Middle East, this annunciation captures both the realism and mystery wrapped up in this pivotal event in the God’s great story of Redemption.

For six week in 1897 Henry Tanner visited Palestine and Egypt in order to experience its culture. He brought back to his home in Paris actual household pieces to use as props in his paintings as well as sketches he had made in the Holy Lands that included people and colors. He wanted to create a more authentic depiction of the Biblical world to give his work both physical and spiritual integrity. The Annunciation includes an oil lamp, rug, and jugs. Not only is the environment of the painting realistic, but Mary does as well. She is not an otherwordly saint, but a young girl who has been awakened from her sleep. Her blanket is half off the bed, and her dress looks slightly wrinkled.

The arches of the back wall, Mary’s peaceful, tilted head, and the blue garment in the front corner allude to early Renaissance annunciation paintings. But aside from those details, this painting stands alone in its realism, in its mystery, as well in its imaginative, startling way the angel is depicted. This is not a painting one easily confuses with Giotto’s or Fra Angelico’s annunciations. Neither is it easily forgotten.

Gabriel is a strange, radiating pillar of light. The moment Tanner captures on the canvas looks as if this messenger from God has already spoken “Do not be afraid, Mary, you have found favor with God.” Although we do not know if he has spoken the rest of his message, there are several clues that help us see the transformative moment Tanner seeks to communicate to his viewers.

Once we have taken in the pillar of light, we look over to Mary and see her face illuminated by his light, as well as the corner warmly highlighted. Our gaze will linger on Mary’s expression; she shows no fear, despite the unexpected night visitor. She looks humbly yet intently at him. Her hands are peacefully folded in her lap. Within this story, the angel continues his message when he says, “You will conceive and give birth to a son, and you are to call him Jesus. He will be great and will be called the Son of the Most High…. His kingdom will never end.” (Luke 1:31, 32)

![]()

This is the powerful moment where Mary is transformed by grace into a faith that is hers. Her expression of peace is our clue. Her words will be of submission: “I am the Lord’s servant… May your word be to me fulfilled.”

Tanner’s goal is not to say Mary has worked up this peace and obedience by her own will. The work of faith is one of mystery and comes from outside of herself. The strong vertical line of light—Gabriel—is perpendicular to a the line of the shelf next to him. These two lines form a cross, a foreshadowing sign of Christ. Also, looking closely, one can see three jugs — in the left hand corner, on top left shelf, and the right wall. When drawing a line from jug to jug to jug, they form a triangle—a symbol of the Trinity. These elements of the painting highlight that it is the cross of Christ and God’s power that transforms Mary and gives her the faith to obey. And it is His presence that gives her the courage to live into the unknown of being an unwed mother, carrying a baby given to her by God for his purposes.

The Holy Family by Henry Tanner was created in 1909. In the ten years between his successful The Annunciation and this Holy Family, Tanner began to move away from the realism that characterized his earlier style, as influenced by his teacher, the painter Thomas Eakins, and to move toward a more expressive style, as influenced by the Impressionists. The years following this painting he would still paint biblical narratives but with a wide variety and shades of blue and light. He would continue to pursue excellence, artistic integrity, and also spiritual integrity.

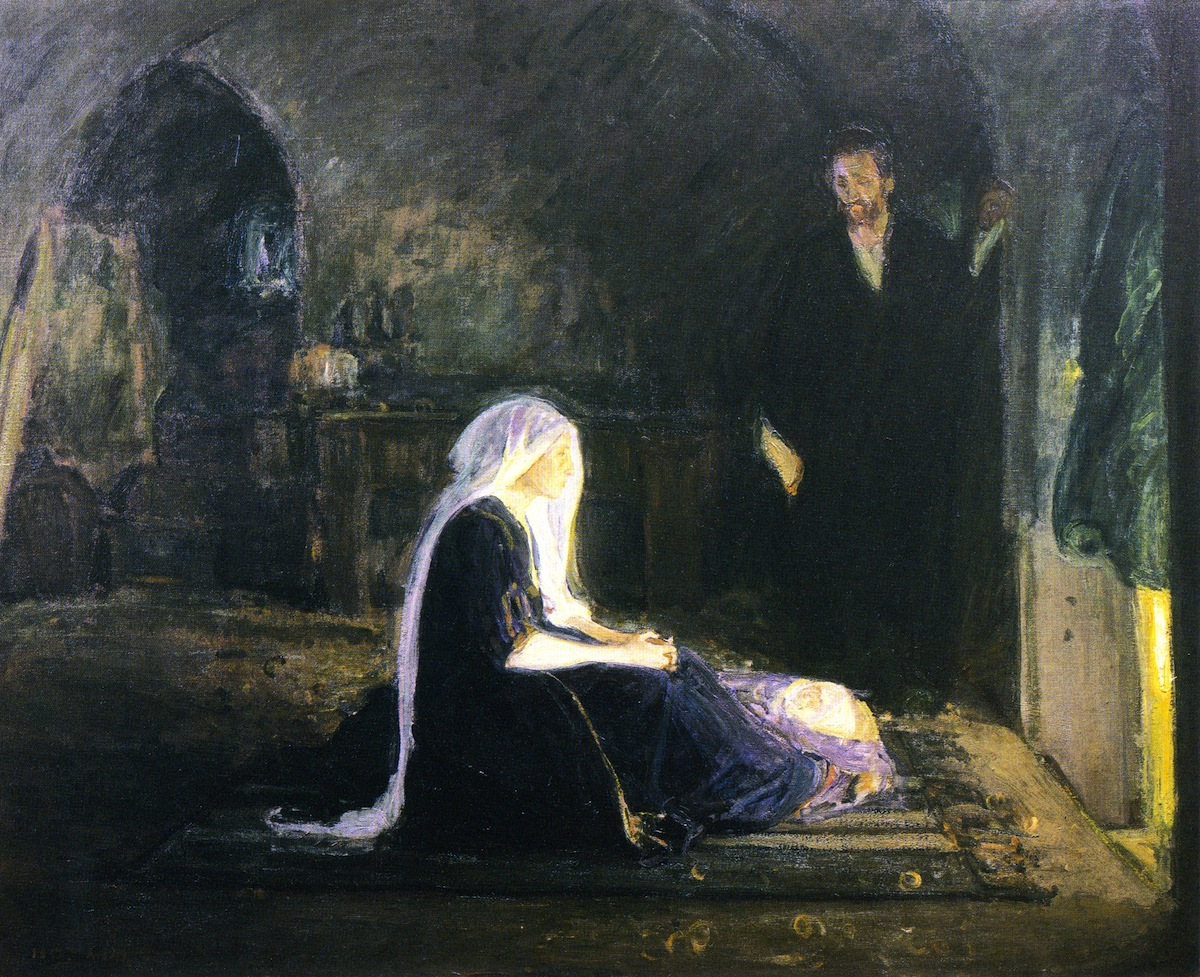

The Holy Family does not depict a specific Bible story. Joseph and Mary look like an ordinary couple in their home. James Romaine, in his commentary on this piece, highlights how this holy couple are made accessible to the viewer by Tanner placing them in a room that is mostly in the shadows, making a table and other pieces in the background hard to decipher. The room has a timelessness to it, which helps us enter into the event.

The angle of the composition is a welcoming tool. We see it not from above the room and over the couple, but into the room and towards the couple. Joseph, leaning on the wall—partially shadowed, attentive to Mary—looks as if he could put his finger to his mouth, turn towards you and whisper a gentle “shh.”

The light moving into the space and onto Mary is reminiscent of Rembrandt’s painting Landscape with Rest on the Flight into Egypt. In this painting, shadows of trees, hills and sky surround the family, as they shelter under a cover of branches. A fire illuminates them just as we see the light illuminating Mary and Joseph in Tanner’s painting. Another Rembrandt painting—The Holy Family with St. Anne—also is a reminder of Tanner’s holy family. Here they are in an indoor scene of Joseph’s workshop. Light comes in from the window, and Mary nurses Jesus. It is a common scene—one that makes this family familiar to us and illustrates that blessings and grace can come into our everyday lives.

In Tanner’s painting, the source of light in the right hand corner is a mystery. Mary peacefully sits on a rug with her hands in her lap. Her veil glows in such a way it looks like a halo. Baby Jesus is sleeping next to Mary, and although the light is on him too, he is barely visible. They both radiate this light. As James Romaine points out, she is sitting towards a light from an unseen source, in an attitude of deep devotion, and with her baby. This light is symbolic of Christ’s incarnation. And here, the ordinary meets the sacred. The transformative power of grace Tanner captures is the moment Mary is given is to see Jesus as her son and her savior.[2] His presence in her life is a blessing and a mystery.

This simply titled oil painting Mary was completed 1914 and has its home in the Smithsonian American Art Museum. After 1900, Tanner did not experiment with any more new painting trends. He continued to work in his expressionistic style. And many of his paintings from this time are done with a dreamy deep blue, such as Daniel in the Lions’ Den and The Disciples See Jesus walking on Water. Some of this blue is in this painting of Mary.

Mary sits on the bed, holding a light, which is almost in the center of the painting. Tanner, although using expressionistic and impressionistic styles, still remained a naturalist. The light is coming from a natural source, one we would recognize in everyday life. Notice how the light she holds lands on her stretched arm, and this leads us up to see her face. See how Tanner does not leave out the folds of her dress, the wrinkled sheets, and the softness of her veil. Behind her on the wall the shadows are dark and in various shades of gray and dark blue.

Mary’s head leans slightly forward. The shadowed lines on the wall help our eyes follow her gaze out of the picture frame. We do not know for certain what she is looking at.

But between the dark and the light, she sits and waits.

Usually pictures of Mary holding a lighted lamp signify that Christ has come into the world. In the annunciation painting from 1898, there is an oil lamp on the shelf in the upper left hand corner. It is not lit. Christ has not yet come. Here in Mary, she holds a lit oil lamp. Her courage and peace come from the Light of the World who is with her.

Here is the space between the treasure and the sword, between the joy and the sorrow.

Henry Ossawa Tanner by painting Mary between the dark shadows and the lighted oil lamp suggests to us that the presence of Jesus and the transforming moment of grace entering into our everyday lives can make it possible to move in that space, whether with laughter or with tears, holding courage and peace in our hearts.

Let me learn, O Lord,

What it is to live so open to life and hope

That I might weep and rejoice

In the same breath

Without contradiction.[3]

![]()

Author’s note: Pittsburgh-born Henry Ossawa Tanner was not only an important American painter, he is also America’s first notable African-American artist. His career, although started in Philadelphia under the tutelage of realist Thomas Eakins, flourished into a successful European and American career after he moved to Paris, France. He was supported by patrons, won various awards, and inspired many African-American painters.

If you want to learn more about Tanner and his art, check out James Romaine’s Seeing Art History.

The Annunciation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zs44P8zgfm0,

The Flight into Egypt: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3QZYlGMOFCA

The Holy Family: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xW0OP8kFcwk

Christ and His Mother Studying the Scriptures: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6GMl63pNudM

[1] Many of my observations here on Tanner’s The Annunciation and the Holy Family are quotes or ideas I have gleaned from Seeing Art History, a video series by art historian James Romaine.

[2] James Romaine, Seeing Art History, 2017, The Holy Family (see link below)

[3] Douglas McKelvey. Every Moment Holy, Volume II Death, Grief, and Hope Nashville, TN Rabbit Room 2021 page 128.

Leslie Anne Bustard takes great joy in loving people and places, whether at church, around her kitchen table, in a classroom, or traveling around. She delights in words, and marvels at the beauty found in the details of ordinary life. Reading, writing, teaching literature, baking, producing high school theater, and museum-ing are some of Leslie’s favorite things. Leslie is the host of The Square Halo, a podcast for Square Halo Books and is developing a book titled Wild Things and Castles in the Sky: A Guide to the Best Children’s Books. She and her husband Ned have been married for 30 years and live in a century-old row house in Lancaster City, where they raised their three daughters.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

Add a comment

0 Comments