Two mornings ago, I stared at the black earth in a corner of my friend’s backyard. I had been sitting on a red bench lost in some thought for several minutes when a small yellow leaf appeared brightly against the earth. It had been there all along, but a long time passed before I became aware of its presence. Poems are like that. They come into view slowly. What did Emily Dickinson say? “The truth must dazzle gradually / Or every man be blind.”

“Thankfully for now, God is invisible.”

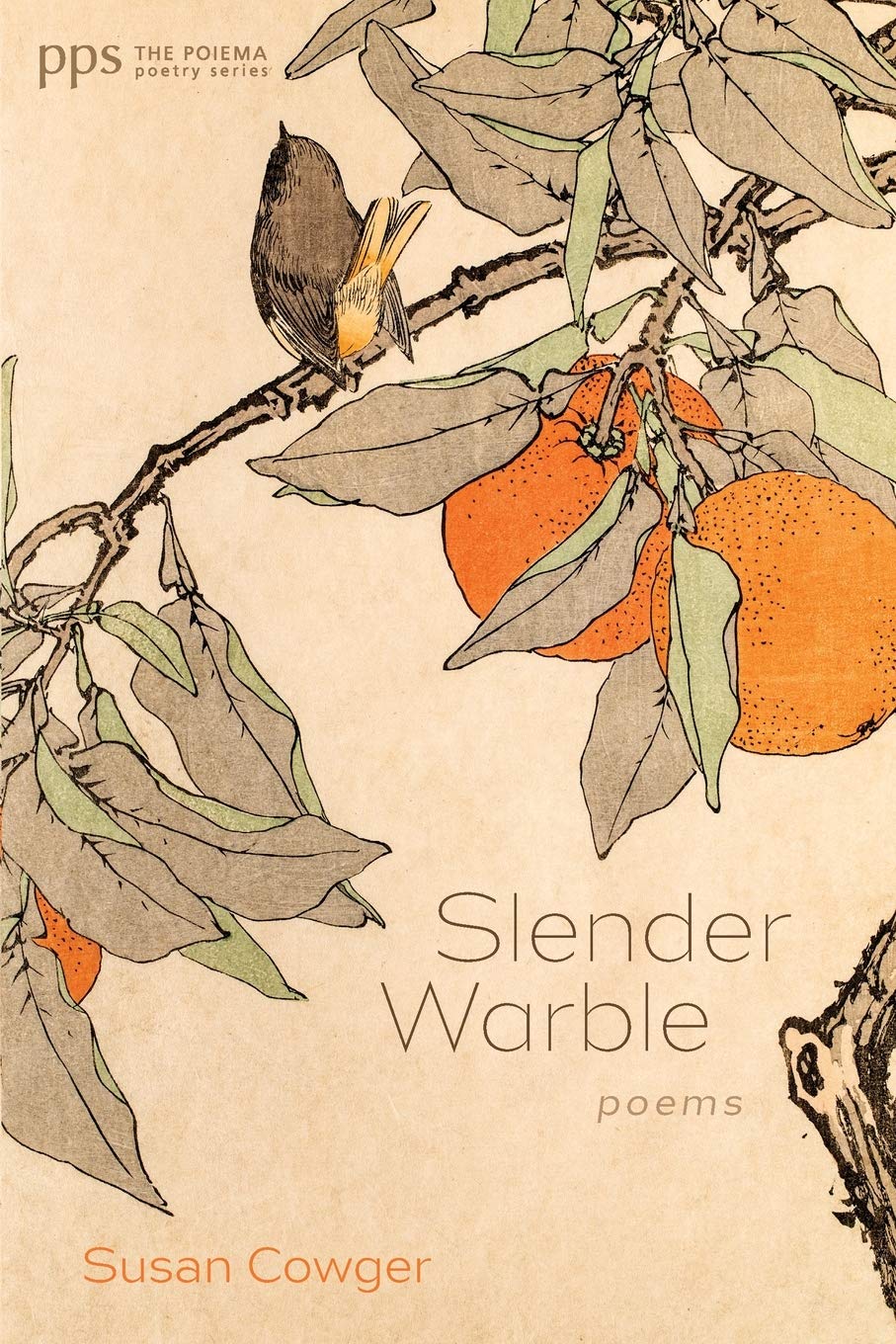

Susan Cowger begins Slender Warble, her collection of seventy-five poems, saying that though we’d like to see God “nose-to-nose” that really may not be the best idea in our present state. We’re just not substantial enough, as C.S. Lewis points out in many of his writings. Cowger sees this as an invitation to listen closely to the ways in which God does make himself available to us through a “song that was not only made for you, it was sung to you”, a song that is “no more than a chirp filtering through the noise of life.” Maybe God’s dazzling presence is parceled out in these slender slow syllables—a word waiting patiently like a little leaf coiled against the black?

Recently, I found it helpful to have philosopher D.C. Schindler point out that the word “immediate” means “not-mediated.” We have never had immediate contact with God, though God mediates contact constantly and in myriad ways through Creation. Faint and tremulous as the chirp-song may be, Cowger assures us something real is being mediated, something made for us, given to us.

If that’s the case, if all of Creation is the medium through which God mediates the song, then it follows that Our Lord’s voice is likely to show up in the most unlikely places. We expect it in beauty, of course, but as Cowger shows us in these poems, that voice may pipe up in the story of torn skin, death in a train tunnel, running water, orange peels, cancer beds, or even the breathless terror of watching a child fall out of an apple tree.

The “Burden of Sweetness”

Good poets are intercessors, a kind of trembling volunteer willing to raise their hand in a crowd and pioneer some bewildering human experience for us. The slender warbles they listen for in the noise are like long-lost blazes marking a way through an overgrown and obscured path. Marilynne Robinson says in her novel Gilead that to be ‘useful’ like this is to be brave and to be brave is to be generous and to be generous is to be vulnerable.

In the opening poem “Weather Report”, Cowger writes that after finding a bunch of dead bees on the porch she will

…Climb

a ladder scout for the hive

and the burden of sweetness

somewhere inside these walls

The honeyed hope the path promises comes at a cost: the drones lay down their lives. Our poet decides to climb a ladder and scout for the sweetness that was worth their death, but it’s not immediately apparent; it is hidden in the walls somewhere. Before that honey can be poured out, “clear cellophane wings / [are] spilled stepped on” and someone must go climbing, scouting, searching for the reason.

How much hidden honey is there in this world, served up “somewhere inside these walls”? Who has died for it; who has searched?

In The Tunnel

Our poet organizes this collection into four sections: In The Tunnel, Between Two Hands, Is That You?, and A Voice Clears. In this first section, I appreciated Cowger’s refusal to take life or death for granted. Sentimentalism is ultimately a refusal to be present to the way things really are, escaping the pain (and joy!) of reality. In “Promise Remembered” Cowger gives us a terrifying image of two lovers in a tunnel facing a train:

What is it about a promise

that resolves to outrun a train

the black smell of creosote

and the scream of steel

This one doesn’t tie up in a bow. It ends as,

…his hands loosen over her ears

an opening so tender

she will never forget

We’ve been taken deep into the tunnel, into the heart of the screeching trainwreck, and we’ve lost much. But what must it be like to feel the hands that pushed you from the tracks and cupped your ears from the noise gently open as they collapse in death? To put us in touch with that touch reminds me of the moment the grandmother in Flannery O’Connor’s short story “A Good Man is Hard to Find” says to her killers, “Why you’re one of my babies.” Cowger is looking for the smallest pricks of grace speaking. “Where might the Lord be in this?” she asks for us. We’re urged to keep looking at the bloody tracks to find God’s tender imprint.

This first section, beginning early with a poem about death in a train tunnel, closes with two poems about life emerging into the light from the darkness of another “tunnel”. These two poems about birth, “Notes from the First Job” and “The Clouds and the Glory,” seem to track together as:

The mouth opens

with one terrifying need

to breathe

And from that first sharp intake of air

you understand hunger

you will never not love

If our time in the tunnel is about hunger and learning to love it, to welcome our “terrifying need”, Cowger begins the last poem of this section with these words:

The shock of God with us

Awakens a throe

Not unlike a baby

Gasping from gusts

And closes with:

a blanket thrown

over your head

and next to your ear

It’s ok it’s ok

Between Two Hands

I grew up deer hunting in the South, and I’ve written about that experience before—how it taught me in the most tangible terms that life is a gift bled out from the death of another. That strange and apparent juxtaposition of life coming from death took shape in my imagination long before I knew much about One who went silent as a sheep to the slaughter. “Go Ahead Do It” depicts a deer hunt:

dragging the warm buck and its crimson aurora

back to the truck I wonder who else has looked into the grey

fog of lifeless eyes trying to make sense of something

like permission

looking down from a cross

Cowger, in this second section, traces these blood-lines through our experience. How are we to hold together life with the contradictions of death? Can we hear the Slender Song even here?

Can we hear it from a cancer bed? The poem “Things I Saw In Her House,” which doesn’t shy away from a mother losing her daughter, reads:

…Why

mystifies and collects on the mirror

She towels it off in the morning stares

into the eyes of faith

and wonders what exactly that means

now

There are so many striking poems in this section. To touch on a few lines here and there, Cowger carefully shows us shame: “savior of a wound I created / as if I could believe you would come and love / what I hate.” There is “the brine of your iris” that sees the coming hurt (“deceit under a brow”) too lately in hindsight. She explores learned self-sabotage: “there will be such goodness / you won’t even want an apple.” Or there is the delicious taste of “Having The Last Word”, but the sweet last word, once it is spit out, lays repulsive like a slobbery piece of candy on a dirty sidewalk. Cowger’s honest look at the ways we are hurt by others and the ways we hurt ourselves is insightful, and oddly comforting; we don’t have to pretend either way. This section’s back-half leads us through losing, grieving, and remembering as death comes.

In the midst of all of this we’re given a pair of poems, “Embalming Tears.” Tears that embalm what is leaving us and perhaps tears as a balm for the bereft. In the second of the two, we watch a man getting into a fishing boat…

… the forced

hardship shoving him off to

God knows where He slouches

Cowger effortlessly blends images of tears, foot washing, fasting, arks, and the story of Noah, ending with,

no dove no olive branch

no rainbow

The loss we experience here “between two hands” is very real. Still, the first of these two poems ends in a kind of eucatastrophe:

One must air-dry this trembling

twist & sling the lave and as

the slough of prayers fly

back to the sky

birds arise from nowhere

That “nowhere” is somehow situated over the course of the poems as they work in conversation together, as earlier in “A Bucket Goes to the Well Empty,” Cowger says,

… The arms of a basin

Encircle the lunacy with goodness

As if perfection has always been there to hold the flaws

Is That You?

Maybe by now we’ve been trained by these poems to lean in enough to ask of whatever we encounter whether Jesus is making some appearance there, however slight? It may be that something has been loosed that may allow our senses to perceive God’s tenuous tune threading our experience incredibly the way

seeds melted from resin’s captivity

by fire irresistibly grow and grow

Our poet continues to look, even if it is with a headache from squinting. “God as Water” shows us “cheeky” surface swimmers dragged deeper by the riptide, broken-toothed, with “ragged questions” bleeding. But those “wounds ground”—in the sense of grinding a person into the ground, grounding them perhaps from the flightiness of flippancy towards God, and grounding them in something more solid, real. Cowger writes,

When God is ocean

beauty and power breaks

every perfect shell

If we go looking for the Lord, we must be willing to have our false selves shattered.

Later in this section, Cowger gives us drafting as an image for following God in prayer. Drafting is when cyclists get as close as they dare to the rear of another cyclist or vehicle to reduce drag from the wind. Racing after the bumper in front of you creates a still place within all that rushing speed while you “stare into the backside of light.” Here, in answer to God’s call, obedience, danger, self-expenditure, exhilaration, and rest coincide.

A Voice Clears

This fourth and last section begins like the three previous sections with a poem called “Weather Report”:

Top lit thunder heads

O fearful breasts of heaven

Our mouths open wide

The language seems, at this point, to intensify and to become at once more playful. “In a Strange Land” describes a tectonic shift:

Let’s call that bump a Kiss

something like Uh-Oh

as if the whole kibosh was

born for trouble sparks

flying upward

morning and night

flipping over each other

and light O Dear God

light running wild

color breaking all the rules

amid the warm eloquence of heat

Holy God you command the fire

Wildness, uproar, collision, and heat all become elements of eloquence. God is speaking, and a new land is taking shape—one that is “nameless and virgin” in which we are no longer alone.

We move on into several water-themed poems. “Fast Water” puts us in the swimming pool: “there’s a rhythm / to small obediences Baptism / disguised as laps”. “Watch This” offers us an image of being washed during confession:

the weight of release

that winks of free fall

that brief but perfect sphere

of mirth descending.

And, brilliantly, Cowger offers us something of an image for metanoia as we find ourselves taking breaths

as a swimmer swimming

into the deeps

where it is hard to imagine

wanting or needing anything

other than

a simple turn of the head.

Returning to images of birth, a couple of Advent poems appear. We run with the shepherds to the stable as they repeat the Herald’s song, saying,

Oh don’t let me forget

how the last syllable unfurled joy

goodness

only God can pronounce.

The Voice continues to clear in “The Reason for Song”: “A gauzy curtain parts / Evening’s breath eases through the window / It’s an upper room” where “His voice begins again” as Jesus washes feet and starts up a hymn

in the range of calling forth

Creation Not so loud as to scare you

just enough vibrato to enclose each note

with a ripple that will spread.

The song that we hoped to hear at the outset has penetrated the world gradually, yes, but definitely; though “not so loud as to scare” us. And it may be that the slender warbling song itself, like honey hidden in the walls, is even voiced by the voicelessness of death, as dead bees signal that secret sweetness.

This is a rich collection worth taking the time to attend to carefully. And it’s good to remember that poems, like persons, won’t be solved. They resist the possessiveness and boxiness of comprehension and call for the hospitality and affection of apprehension. They withdraw when we make demands and put the screws on them; but they cock their little heads and tip-toe toward us when we wait very still, listening.

Someone taught me to swim as a very small child. At the pool, there were these very tiny insects called Sweat Bees (we called them Sweetbees). They skitted about, stopping to hover. Our instructor promised that if we were still enough and held out our forefinger like a tiny landing pad, the Sweetbees would sometimes alight and dally on our skin. It can happen, and when it does you feel the slightest eddies of air against the nerve-rich tips of your open, waiting hands.

The featured image is courtesy of Julie Jablonski and used with her kind permission for Cultivating and The Cultivating Project.

Susan Cowger’s beautiful book of poetry can be found at Wipf & Stock Publishers and Amazon.

Matthew Clark is a singer/songwriter and storyteller from Mississippi. He has recorded several full length albums, including a Bible walk-through called “Bright Came the Word from His Mouth” and “Beautiful Secret Life.” Matthew’s current project, “The Well Trilogy,” consists of 3 full-length album/book combos releasing over 3 years. Each installment is made up of 11 songs and a companion book of 13 essays written by a variety of contributors exploring themes around encountering Jesus, faith-keeping, and the return of Christ. Part One, “Only the Lover Sings” is available both as an album and as a companion book.

Matthew also hosts a weekly podcast, “One Thousand Words – Stories on the Way,” featuring essays reflecting on faith-keeping. A touring musician and speaker, Matthew travels sharing songs and stories in a van called Vandalf.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

Matthew Clark,

thank you. Those two words encompass so little of what I want to say. Therefore, I follow it with something the asians have honed–a bow of respect.

Your review of my book encompasses more of my thoughts and being than I thought possible.

You capture the essence of Slender Warble. how the Presence of the Lord is not tied solely to miracles, that the slightest glimpse of it is miraculous. Life changing.

I’d guess you’ve, seen Beauty in the mundane that has made you cry and have been to what I call the Howling Place. And found Him there.

may the goodness and Presence of the Lord be found by us all. He will be sure of it.

Susan

Susan! I can’t tell you how honored and thankful I am to hear you’re happy with this piece. Thank you for your poetry, I am grateful to have had the chance to read it and write about it here.

I think I do know what you mean about the “Howling Place”. And He did show up there – He “beat me to rock bottom”.

I hope more folks spend time with your work. It’s a good gift to us.

Oh thank you, Matthew! For those of us who are faint of heart at the thought of reading poetry, you have written an essay that entices me to step into the water and get my feet wet! And thank you, Susan, for writing poems and sharing them with us. I look forward to wading.

So sitting on the porch with the hummers still buzzing for a drink of nectar, I sat and read this essay again. It is true that the words don’t make sense the first time. I admit that a third or more reading may be necessary to really get it! It is amazing how the abilities of the two people can bring a place to rest and listen and look for what those poems bring.

Thank you Susan for your poems and thank you Matthew for your making them more.

Oh my oh my…. This is a piercingly accurate rendering of the heart of susan’s book, Matthew. Remarkable. The lens you hand us to read her work is a gift; I’ll need to grab my copy and re read.

Well done!

Thank you, terri, and I’m one of those faint of heart about poetry, too! Ha!

Matthew, this is more than a thoughtful poetry review. It is heart-ful as well. You not only open the door for others to get a glimpse into the book, you model how you engage with the poems, and entice your reader to join you. And your last metaphor–for poetry, and for this book in particular–is so arresting. Well done.

Matthew, there is so much richness here. I love the way you model your engagement with the individual poems, each section, and the book as a whole. The layers of this review unfolds the layers of this book with wisdom and grace.

I love how you close with a reminder of what poetry is–and isn’t: “And it’s good to remember that poems, like persons, won’t be solved. They resist the possessiveness and boxiness of comprehension and call for the hospitality and affection of apprehension. They withdraw when we make demands and put the screws on them; but they cock their little heads and tip-toe toward us when we wait very still, listening. ”

And then, your final metaphor. It makes me want to keep my nerve-rich hands open to both the pain and the joy that each moment is bringing. I am more human both for Cowger’s poetry, and for your review.