Karen Swallow Prior presents a remarkable voice of clarity and courage in a world so very often lacking both. It is our honour to interview Dr. Prior for Cultivating about her newest book – On Reading Well – and what it is to live the good life.

LES: Karen, six years ago you wrote a marvelous book titled Booked – Literature in the Soul of Me. It also focused on classic literature and reader involvement, yours specifically. Given that On Reading Well also focuses on classic literature and reader involvement, what are the differences between the two? Why did you to write On Reading Well now?

KSP: Structurally, the two books are similar: each chapter focuses on a work of literature or author and is connected to a theme. In the case of Booked, each theme was a stage in my life and my spiritual journey, from childhood to adulthood. In On Reading Well, each work or author is examined in the context of one of the classical virtues. I did not set out to write about the virtues so extensively, but my editor suggested at the book proposal stage that I focus somehow on spiritual practice. It was very early in the writing process that I got the idea of centering on the virtues, a topic that has long fascinated me but one I did not know much about. I enjoyed the research I did to write the book, perhaps even more than the actual writing! Both books focus on the formative power books have, particularly good books, well read.

Defining “the good life”

LES: Is it part of your purpose in writing this book to reframe reader’s understanding of what is meant by “ the good life” and what it means to live it?

KSP: Yes, exactly. The phrase “the good life” comes from Aristotle, and is sometimes translated as “happiness.” For Aristotle, what made human life “good” was fulfilling our purpose as human beings. He identified the qualities of humans that are most excellent—qualities such as courage, temperance, prudence, and others—and called these “virtues.” In short, the good or happy life, according to Aristotle, is the virtuous life. Interestingly, the founders of America actually were alluding to Aristotle’s understanding when they claimed the right to pursue happiness as part of the Declaration of Independence.

But this is a sense we, sadly, have lost: the idea that happiness is found in our character, not our circumstances.

LES: There are only a few spots in Scripture that use the term “the good life” but it is illustrated throughout the whole body of God’s Word. One instance of this phrase is beautifully set in Ephesians 2.10, a verse I discuss often with Cultivating readers, and with attendees in talks and workshops.

“For we are God’s [own] handiwork (His workmanship), recreated in Christ Jesus, [born anew] that we may do those good works which God predestined (planned beforehand) for us [taking paths which He prepared ahead of time], that we should walk in them [living the good life which He prearranged and made ready for us to live].” Ephesians 2.10

Is there a link between Aristotle’s understanding of the good life and what is being said here in the New Testament? How does a contemporary Christian who truly wants to live out the good life that God has made for them best do that in the surroundings of such conflicted cultures as we live in today?

KSP: As a philosopher of the pre-Christian age, Aristotle’s view certainly is incomplete from a Christian perspective. As important as good character is, and as attainable as it is by all human beings simply because we are made in God’s image, it is not enough. But the virtues that Aristotle and other ancient philosophers and later theologians identified are qualities that are unique to human beings exactly because we are made in God’s image. As image bearers of the most Excellent one, we were made to reflect those qualities. We can only do so truly, however, in Christ. Good character and good works are important—but God is the only one who can perfect them.

Cultivating Virtue

LES: Karen, how do you define virtue and what are the conditions for cultivating it?

KSP: I think Aristotle’s definition is best and most helpful: virtue is a mean between two extremes, an excess and a deficiency. In other words, too much of any good quality, as well as too little of it, is a vice. Boldness untampered by wisdom, for example, isn’t courage—it’s recklessness. Likewise, starving oneself isn’t temperance—it’s self-abnegation. We can understand the virtues of humility and justice when we recognize that it is easier to be entirely selfless or entirely self-centered; humility and justice, in their own way, moderate between these two extremes. It is part of our fallen human nature to gravitate toward extremes, to think and move and have our being in the ease of things that are black or white. Holding competing goods and competing truths in tension is hard—but it is what is required of excellence. The image of the cross—two ends stretched out, two stretched down and up, and Christ right there in the middle—is a compelling picture of that crux, that place of tension or balance where we should strive to be.

LES: We are all familiar with the expression “You are what you eat.” There is also a truth that we are what we read. You’ve said that it isn’t enough to read widely, but that we need also to read well. What does it mean to “read well”? Besides changing how we fundamentally think, does reading well change the way we relate to others?

KSP: Numerous studies in recent years confirm again and again what Aristotle argued long ago: literature serves a moral and ethical purpose because it trains our emotions through vicarious experience in ways that transfer to real life. In particular, research has shown that people who read literary fiction have more empathy. This seems owing to the fact that literary fiction requires readers to infer, predict, interpret, and evaluate—much as we must do in our everyday lives concerning people and situations. Just like a muscle that is exercised in practice performs better in the actual game, so our emotions can be exercised and matured through practice. Ultimately, this idea fleshes out the simple scriptural truth found in Proverbs 23:7 that as a person thinks, so is he. What is inside (emotions) comes out in our actions, including our actions toward others.

A taste for slowly acquired beauty

LES: How do we begin to recapture a taste for the slowly acquired beauties in a world of instant delivery?

KSP: Oh, this really is a most important question! I think we begin by recognizing our need to do this very thing. Next, we must acknowledge that even if we realize this is a need, it does not mean our desires will always line up. Thus, we must be intentional and proactive in our practice, realizing that the more we practice anything, the easier it becomes, eventually even becoming part of our character. This is how virtue works. And this is also true of the practice of slow, deep, prolonged reading, the kind of reading that is actually made harder by the time we spend doing quick, fast, surface reading.

LES: This September On Reading Well comes out in the company of two other good books about reading great books: Sarah Clarkson’s much anticipated Book Girl, and Anne Bogel’s I’d Rather Be Reading. Each are different, each are written with love, care, and conviction. Why is there such a hunger right now for books about books and about reading with whole-hearted purpose. Do you sense a craving for literary substance in our culture and a readiness to return to reading well?

KSP: I do sense this renewed hunger! It’s a great time for books—and for books about books. This actually was not true a decade ago when I was first trying to get my first book, Booked: Literature in the Soul of Me. Editor after editor loved it, but most of the publishing boards said, “Books about books don’t sell.” I think the shift is rooted in a backlash against the tyranny of social media, so many hot takes, and click baiting headlines. Our collective heads are spinning, and books offer a respite from all the dings and buzzes. As someone who has loved books my entire life, I want to say to those with new or renewed appreciation for books, “Welcome” or “Welcome back,” as the case may be.

The value of reading old books in new times

LES: I’ve loved Alan Jacobs books How to Think and The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction. Are there books you would recommend regarding reading well in an age of skim and scan reading?

KSP: Both of these books are fantastic. I cite The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction in On Reading Well and just taught How to Think in my writing class last semester. I’d also recommend Slow Reading in an Age of Hurry by David Mikics, The Shallows by Nicholas Carr (both of which I cite in my book) as well as C. Christopher Smith’s excellent book geared toward Christians and church communities, Reading for the Common Good: How Books Help Our Churches and Neighborhoods. The introduction to On Reading Well focuses on how to read better (and why). I wrote it hoping that readers would find that one part in itself worth the price of the book.

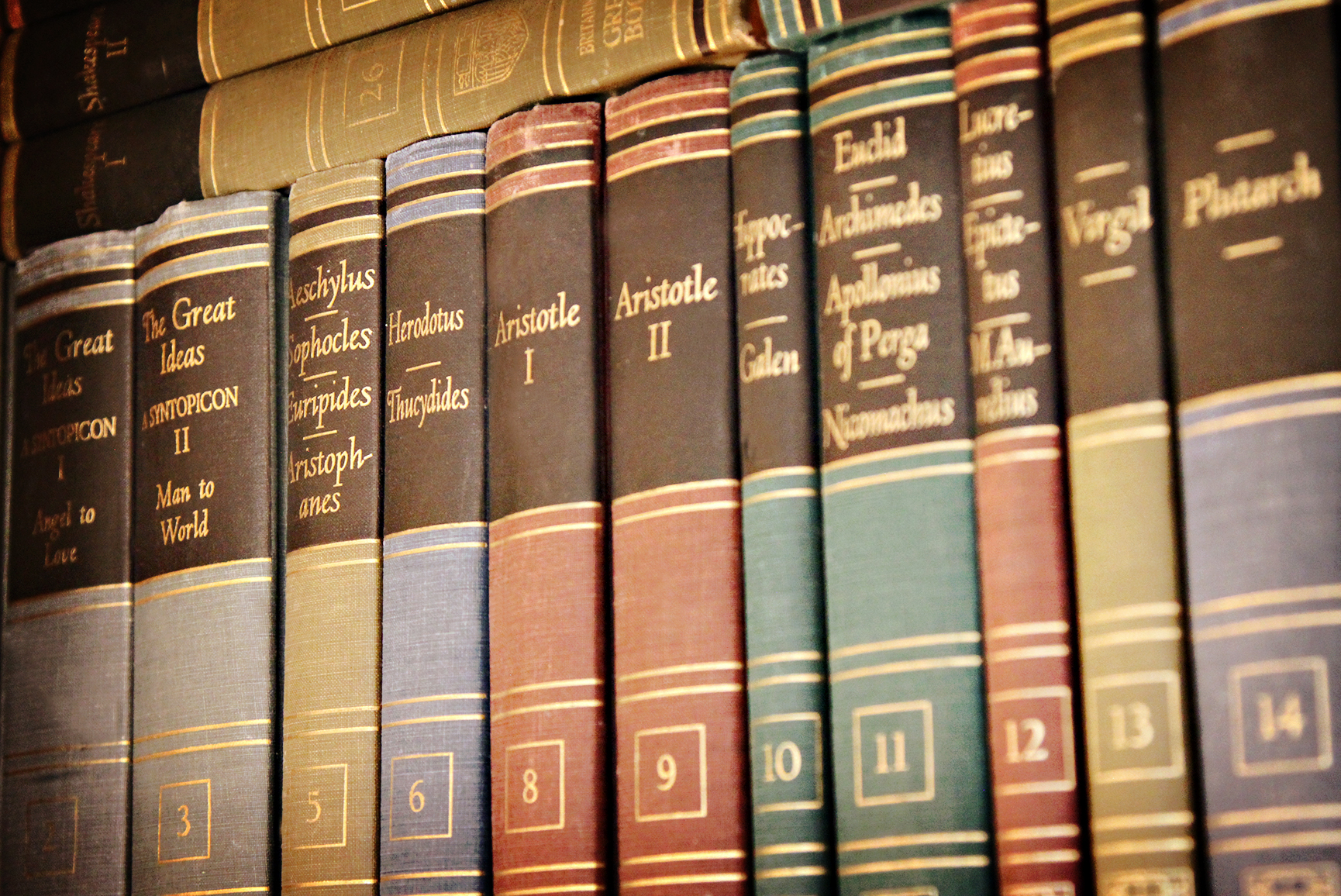

LES: What can modern readers hope to gain from reading old books, books we often label “Great Books” and then set on a high shelf to gather dust?

KSP: One of the things that makes “Great Books” so great is that they invite re-readings. This is why they should be kept on our shelves, even if they do gather dust for a while. They have passed and will continue to pass the test of time and reveal new riches every time we return to them. Most of them offer challenges to readers, whether in their form (style) or content—or both. But it is the challenge that makes reading them so rewarding. They do more than kill time or amuse for a few moments. The best books linger in our minds and souls for days or even years.

Many thanks to Dr. Prior for sharing her thoughts with Cultivating readers, and for her lifelong commitment to teaching. Hers is a brave and beautiful voice!

For further exploration:

Literary Life Review:

Reviews – On Reading Well by Karen Swallow Prior

This is an excellent article about the modern issue and impact of “skim / scan” reading:

Skim Reading is the New Normal

Break Point Podcast Interview by Warren Cole Smith with Karen Swallow Prior:

Karen Swallow Prior – On Reading Well

Dr. Prior’s article in Christianity Today:

Why You Can’t Name the Virtues

Lancia E. Smith is an author, photographer, business owner, and publisher. She is the founder and publisher of Cultivating Oaks Press, LLC, and the Executive Director of The Cultivating Project, the fellowship who create content for Cultivating Magazine. She has been honoured to serve in executive management, church leadership, school boards, and Art & Faith organizations over 35 years.

Now empty nesters, Lancia & her husband Peter make their home in the Black Forest of Colorado, keeping company with 200 Ponderosa Pine trees, a herd of mule deer, an ever expanding library, and two beautiful black cats. Lancia loves land reclamation, website and print design, beautiful typography, road trips, being read aloud to by Peter, and cherishes the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and George MacDonald. She lives with daily wonder of the mercies of the Triune God and constant gratitude for the beloved company of Cultivators.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

Add a comment

0 Comments