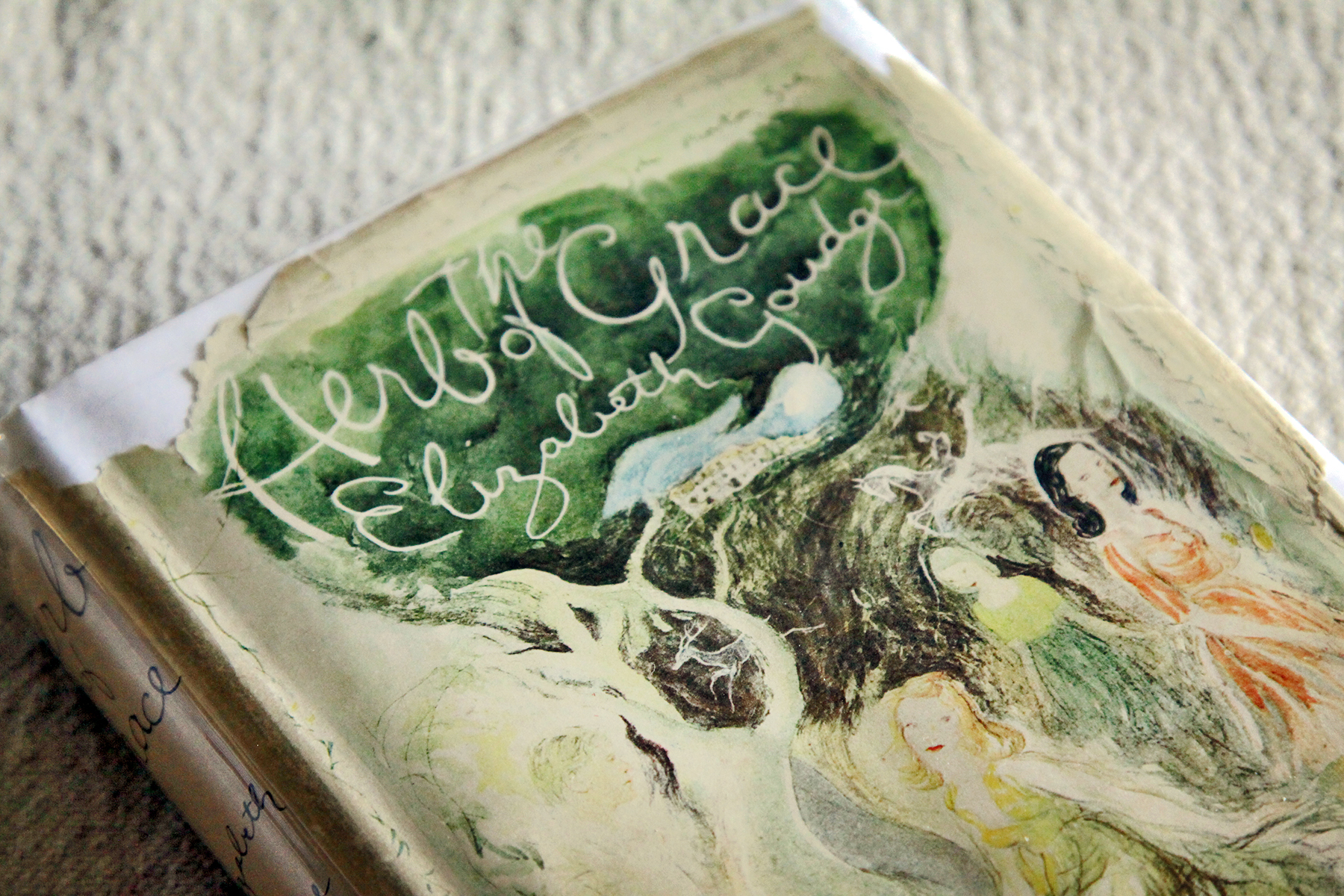

During my tour last November, I stopped in at Peter and Lancia Smith’s to play a house concert and rest for a few days. Lancia offered me Elizabeth Goudge’s The Herb of Grace to read during my stay. I read about twenty pages. Later, this January, back home after wrapping up my traveling, I ordered my own copy of the American printing retitled Pilgrim’s Inn. My first encounter with Goudge’s storytelling has been deeply affecting and, honestly, kind of magic.

I highlight “encounter” here; encounter is a word that originally meant to face an adversary; it’s a fighting word! It may seem strange to say that Goudge’s seemingly idyllic story of a family buying an old Monastery’s Pilgrim Inn enfolded by the English countryside post World War II is about facing adversaries, about fighting, but it is. It’s a story about wrestling, about grieving. It is a story about the restlessness that can only be settled through wrestling. Jacob names the place where he encountered God “Peniel” which means the face of God, because in all of his restless wandering Jacob never found rest until he encountered God. At Peniel, God asked what Jacob’s name was, and Jacob, faced by God, was forced to face himself in that holy place; forced to face his conniving, broken, evasive, exhausted self. “I hate to admit it, but, yes, I am Jacob – that Jacob.”

And then the unexpected and gloriously unlikely thing happens: eucatastrophe; God blesses the beaten wrestler. The loser wins; he wins rest.

Goudge’s Herb of Grace is a book full of Jacobs. All wanderers carrying various regrets, griefs, and secret sins. They are wanderers, but they are not yet pilgrims. The word pilgrim means a foreigner or stranger. In this story, until our ‘Jacobs’ admit that they are strangers to themselves, they will not have begun the journey of a Jacob: the road that leads to Peniel, where the stranger meets herself.

The beautiful irony of Goudge’s story is that these wanderers can only begin their pilgrimage if they are willing to be still. They must root themselves in a particular house with particular people and simply stay put among these relationships. Only in this settled setting of relational rootedness can they begin to encounter the truth of their various sorrows and move through them. Only by being still can they travel into and through the wrestling to the rest they long for.

If all that sounds overly heavy, I should say that the experience of the storytelling is delightful. This is a story about a family discovering a beautiful place where love, friendship, and wonder well up unexpectedly. In fact, one of my favorite quotes from the book that describes its theme of eucatastrophe is this: “The supreme joy of childhood is the expectation that gloriously unlikely things are likely to happen at any moment.” This is a story painting a picture of rebirth and rejuvenation, of becoming like a child again.

All these Jacobs are afraid to turn toward and face their grief, but beneath the crust of fear the narrative is rumbling with an incessant joy, an expectant blessing, ready to burst into bloom at every turning. But this turning is the key; the turning is the willingness to taste the herb of grace, and this bitter herb is rue or repentance. No one in Goudge’s story is capable of this rueful repentance alone; no one is capable of pilgrimage to Peniel without the help of friends who love them. This is why staying put in a family is what makes the pilgrimage possible; it’s what makes repentance bearable; loving encounter with ones who love you is what gives us the courage to journey into the heart of our sorrows where the “gloriously unlikely” is most likely to happen.

In The Herb of Grace, the heart of our sorrows takes place in the old forest behind the Pilgrim’s Inn where our Jacobs all live together. In this ancient forest, our pilgrims lean on one another as each moves closer to, what Goudge calls “the heart of the wood.” The heart of the wood is Peniel. It is the holy place where we make naked contact with our deepest griefs. It is where we look straight into the bitter truth of the pain done to us and the pain we have caused, and turn to see the blessed light of the Face that faces us with the impossible sweetness of joy.

Our hearts, like frescoed chapels whose walls once showed a glowing Image of fruitful freedom, have been buried beneath layer upon layer of decorative protection. The heart that can’t be touched cannot live. The beauty of Goudge’s story is that we are shown the hope that those layers can be peeled back until the bright walls of the heart’s chapel are renewed. The heart can be reborn.

Brilliantly, Goudge frames and enacts the majority of this renewal through children in the context of a family learning to love each other. However, the children are not narrowly sentimental or else you’d feel manipulated into false hope. Instead, they are real family members, adding substantially to the overall complexion of the pilgrimage. It’s the children who often instigate processes of “peeling back” that the adults, more skilled at coping, might not have. Whereas the grown-ups have mostly forgotten how to play in the woods, the children find the heart of the wood before the adults. Chesterton’s saying comes to mind: “We have sinned and grown old; our Father is younger than we are.” Our Jacobs are weary; Goudge, through this story’s children, gives us the surprise gift, not of a return to childishness, but of a recovery of childlikeness.

All of this requires a pilgrimage afforded only by staying put in a family. The Pilgrim’s Inn is the safe place where our wandering Jacobs are welcomed. Where they’ll become pilgrims. From which they will set out to find their heart of the wood. Their hearts will be reborn, not by skirting the edges of the wood, but by encountering the bitterness at its center. Here, a way through appears, leading to a joy set and settled before them: a place for weary pilgrims to find Rest.

Every Jacob willing to pilgrimage to Peniel is met with the supreme joy of childhood – that the glorious unlikelihood of rebirth is joyously likely indeed.

Heart of the Wood

Matthew Clark

Go with me to the heart of the wood

Come walk with me where the trees grow close

This wilderness has bewildered me so

Come and meet me in the heart of the wood

CHORUS

The heart of the wood where the pines keep quiet vigil

Where you end in the place that you fear the most

Just to turn and find a vision:

A way that leads you home to your own heart –

through the heart of the wood

Would your heart like a friend for that road

Some help to face the regret in your bones

There’s no way round it, I think you know that by now

But I’ll go with you to the heart of the wood

CHORUS

BRIDGE

Like a chapel overgrown and long forgotten

There’s a holy place where you have to face yourself

And the image that you find once you’ve cleared away the vines

Is so beautiful you hardly recognize it

Surprised to see the rotten years unwasted

You dropped all your defenses like dead leaves

There in that bitter place you taste it

The sweetness of some fruit you could not see

You held your battered heart out to the quiet

Felt its river wash the stone and soil away

Still among the stillness of the forest

You found the heart to give your heart away

Matthew Clark is a singer/songwriter and storyteller from Mississippi. He has recorded several full length albums, including a Bible walk-through called “Bright Came the Word from His Mouth” and “Beautiful Secret Life.” Matthew’s current project, “The Well Trilogy,” consists of 3 full-length album/book combos releasing over 3 years. Each installment is made up of 11 songs and a companion book of 13 essays written by a variety of contributors exploring themes around encountering Jesus, faith-keeping, and the return of Christ. Part One, “Only the Lover Sings” is available both as an album and as a companion book.

Matthew also hosts a weekly podcast, “One Thousand Words – Stories on the Way,” featuring essays reflecting on faith-keeping. A touring musician and speaker, Matthew travels sharing songs and stories in a van called Vandalf.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

A lovely tribute to this story! I think your chorus highlights a characteristic in this tale & all of Elizabeth’s writing: her ability to take us with her characters to their worst fears & see their redemptive vision in that same place. Beautiful.

Your essay and song have inspired me to take down my old copy of Pilgrim’s Inn and read it again. It is such a beautiful story–and you have written a beautiful song to keep company with it. Thank you!

Man, what a balm of a song. I love the lines, “…Is so beautiful you hardly recognize it” and ”You found the heart to give your heart away”. Thank you!

I really enjoy this song, MR. Clark. Thank you!