For the past few weeks, my imagination has been filled with the paintings of a favorite artist. His unexpected use of colors, especially the vibrancy of his yellows, blues, and greens, is hard to forget, as are his bold brush strokes. Light shines out in most of his paintings, not just those set in the outdoors, but also those ordinary or rejected people he observed and captured on canvas. I have been drawn to him and his artwork because even though many in the church and in the art world rejected him, he found the faith and fortitude to continue painting and to work out the vision that filled his heart. Wider acceptance and success came later; his paintings found their places in museums, galleries, and around the world, making him one of the greats in modern art history.

The reader might conclude my narrative above is of the brilliant and tragic Vincent van Gogh. His use of color and light, as well as his lines, were bold. His subject matter included ordinary people. He was rejected during his lifetime, but became one of the most beloved painters in the world.

However, this particular description is of the French painter Georges Rouault. And like Vincent van Gogh, who influenced him, Rouault was faithful to his vision of what, why, and how he wanted to paint. Although there were many, especially in the Catholic Church, who rejected his work, he held onto his faith in Christ and his faith in his work. He found the courage to stick to the calling he believed God had given him.

Georges Rouault was born in 1871 in the basement of his family home during the Paris Insurrection. At 14, his was apprenticed to a stain glassmaker. Eventually he worked contributing to the restoration of the windows of the Chartre Cathedral, one of the premier examples of Gothic architecture of medieval France. At the age of 20, he started studying under the Symbolist Gustave Moreau, who later encouraged young artist to find his own voice and path.

Another key element to his growth as a painter was when, as a young man living in Paris, he accepted an assignment involving sitting in and recording what he saw in criminal court hearings. “His experience of the corruption of the French courts and the abject desperation that led most of the poor defendants to their crimes left him with little patience for outward displays of correctness and authority.” [1] From this point, seeds were planted for a vision of creating artwork that spotlighted the outsiders of society, such as prostitutes, and how Christ’s grace and compassion was for them. He was disgusted by the judges, by the rich, and by the church—those who did not care for others and believed they were above the law. In 1907 Rouault started painting prostitutes and clowns. The poet Andrew Suars wrote to Rouault about this, saying, “The beautiful style with which you have dressed them is a guarantee of their souls, and that their misery is worthy of salvation.”[2]

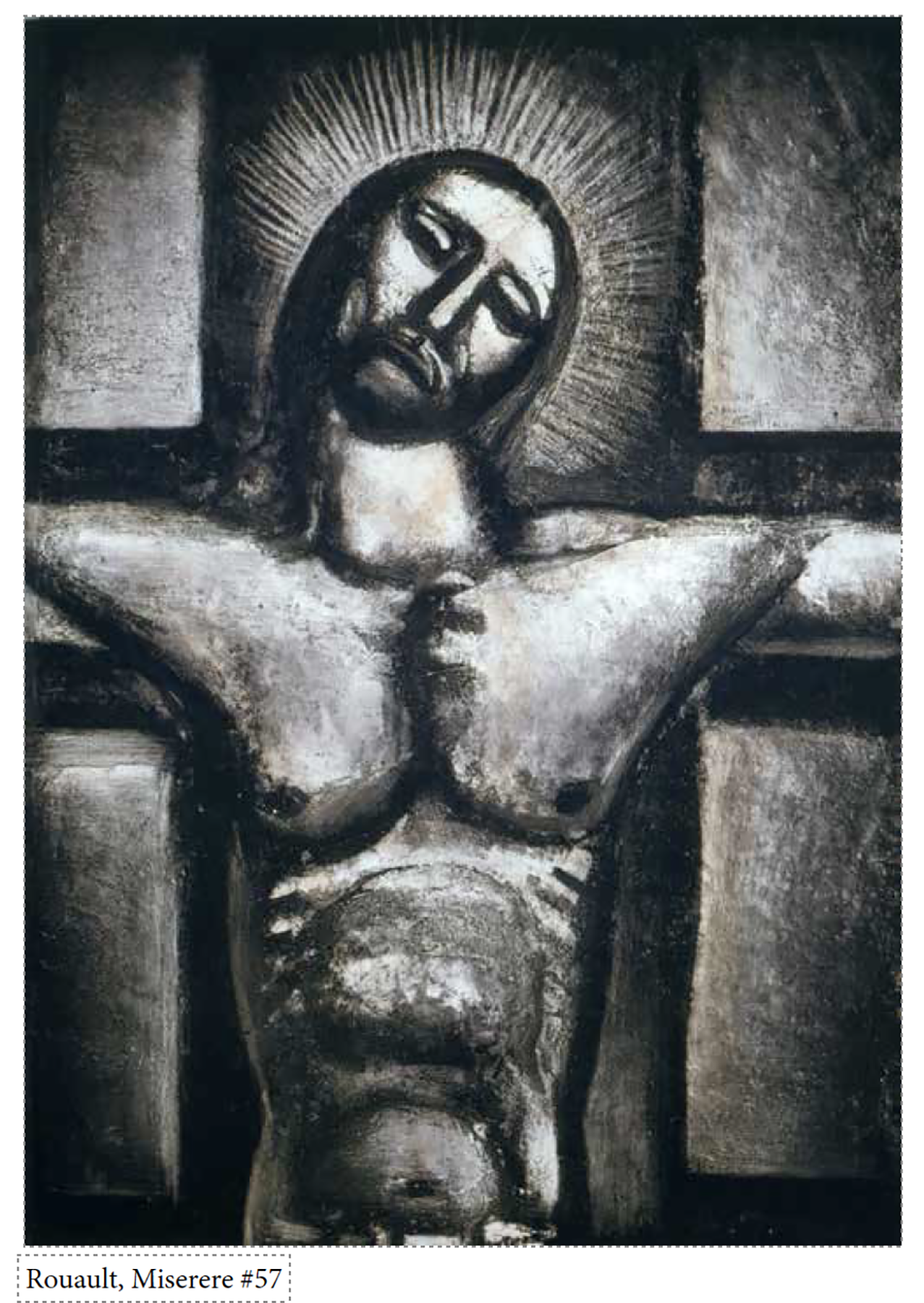

Rouault continued painting, and showed his work in public exhibitions, most notably the Salon d’ Atomen[3]. He also became part of the Fauvists movement led by his friend Henri Matisse. Vincent van Gogh’s work, rich with color contrasts and emotion, influenced Rouault. As he continued painting in the early 1900s, Rouault became a major influence in the Expressionist movement. His works were shown internationally, especially in London and NYC. Around 1917, his Christian faith and interest in the Catholic Church began to impact his art making, so much so that he is now considered the most passionate Christian artist of the 20th century. In 1948, he exhibited his important Miserere series. He had started this in the late 1920s and continued working on it till he was ready to exhibit it. He died in Paris in 1958 at the age of 86.

To celebrate the 150th anniversary of Georges Rouault’s birth, my husband hosted an exhibition of his work in the Square Halo Gallery. Although I had been aware of Rouault before, seeing this work in person inspired me to learn more. I found my interest in his artistic vision—and how his faith in Christ informed his work—grew the more I read about him. His courage and fortitude as an artist of faith, in an era when art and faith were isolated from each other, Christianity doubted, and self-expression was all-important, encouraged me to keep researching him and his artwork.

What does it mean to be a courageous art maker and to practice fortitude in one’s creative life?

The English word for courage comes from the French root word for heart, Coeur. [4] Stephen Roach, in his book Naming the Animals: An Invitation to Creativity, writes, “Courage is to act from the heart. Courage is an inner strength realized with challenging circumstances. It involves a willingness to risk failure, harm, or defeat . . .”[5] He also says, “To act in courage takes confidence and trust that some necessary or desired goods will come from our action.”[6] Claude Monet and Pablo Picasso are examples of courageous artists. They each started their careers pursuing distinct visions of what and why they painted. In the beginning, their works were questioned and criticized; yet they kept on painting. Eventually they both found critical approval, praise, and popularity. Their courage paid off during their lifetimes.

In contrast, Vincent van Gogh and Georges Rouault were art makers of courage and fortitude, but with little acclaim. They kept to their visions, going against the popular movements of the day and not bending to the critics’ harsh words about their work. They didn’t receive all the glory in their life times as they would receive after their deaths.

Georges Rouault was accused of being able to only “imagine the most atrocious avenging caricatures” and being “attracted exclusively by the ugly.”[7] Art Historian William Dyrness said Rouault provoked “pious rage.”[8] Even his favorite writer Leon Bloy told him to quit the direction his paintings were taking. Yet these distractors must not have paid close attention to what Rouault was doing with color, black lines, and subject matter. His colors were bright washes of vibrant reds, golden yellows and oranges, antique-like blue-greens, with energetic and loose brushstrokes. His bold black lines, which created the forms in his paintings, were filled with these colors. Rouault used color combinations that art teachers often tell their students to avoid. Makoto Fujimura shared, “Bright yellow and sharp purple never should work well on painting, nor muted color mixed with black—in his hands these impossible colors speak deeply and resonate.”[9]

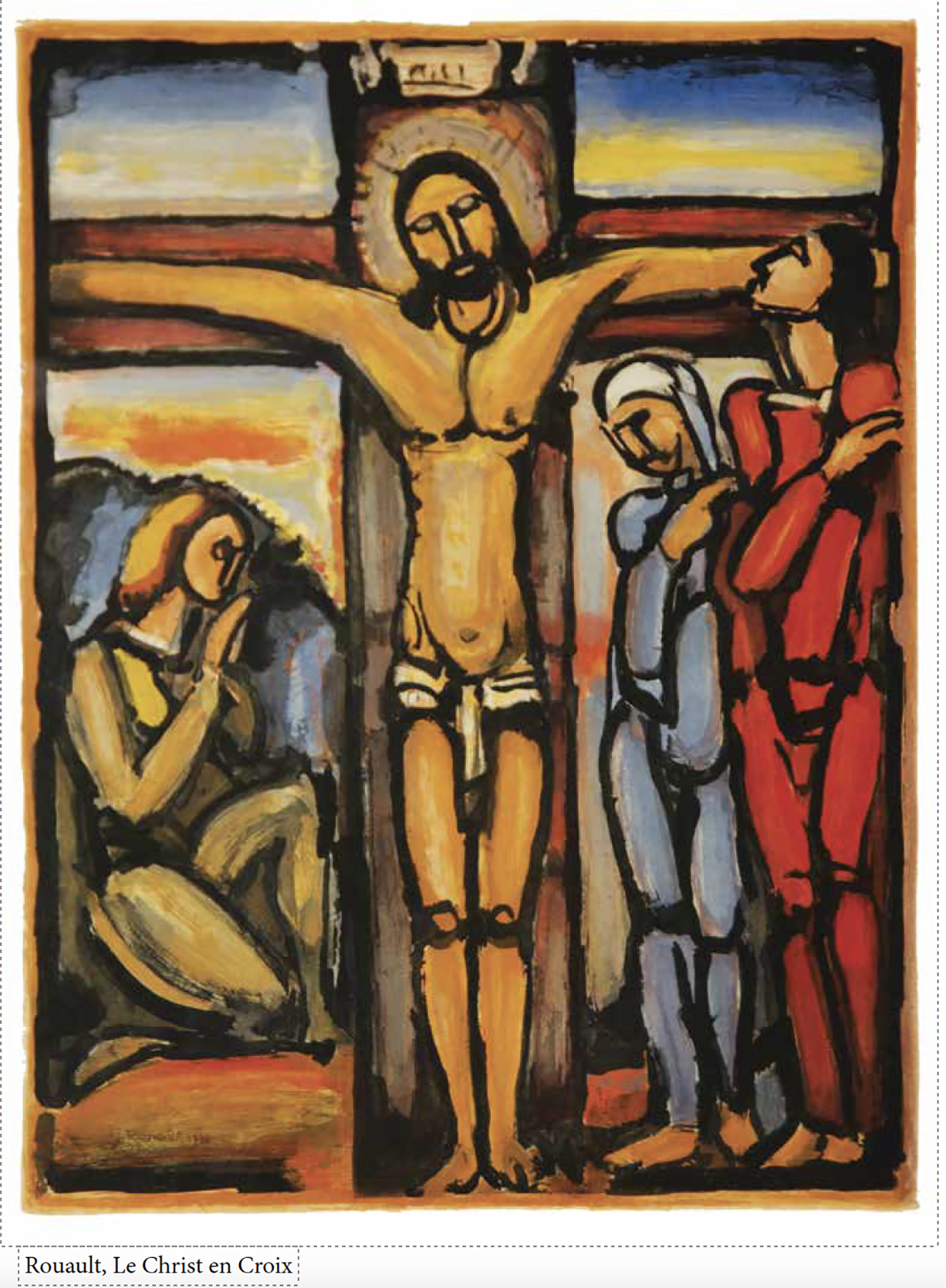

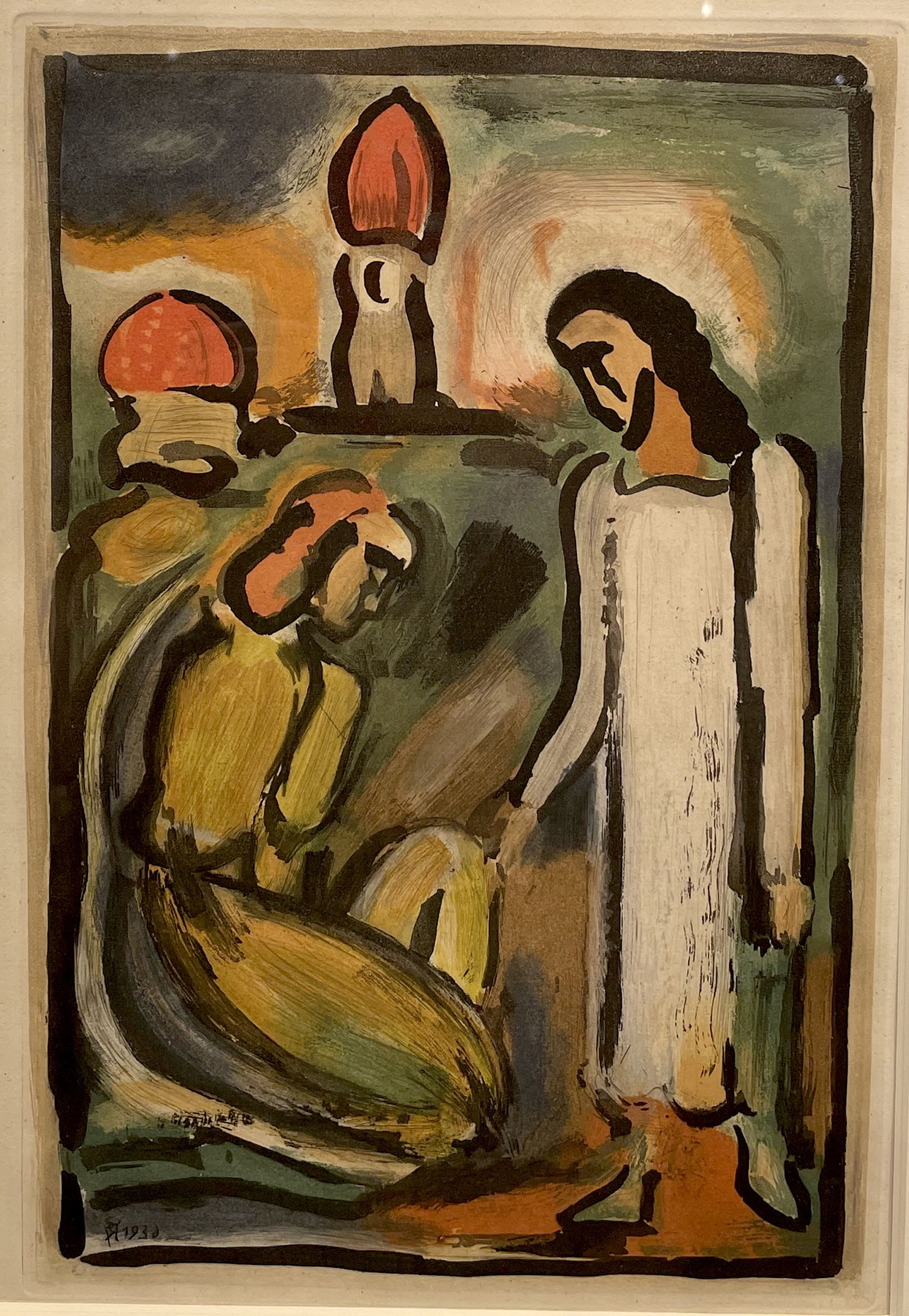

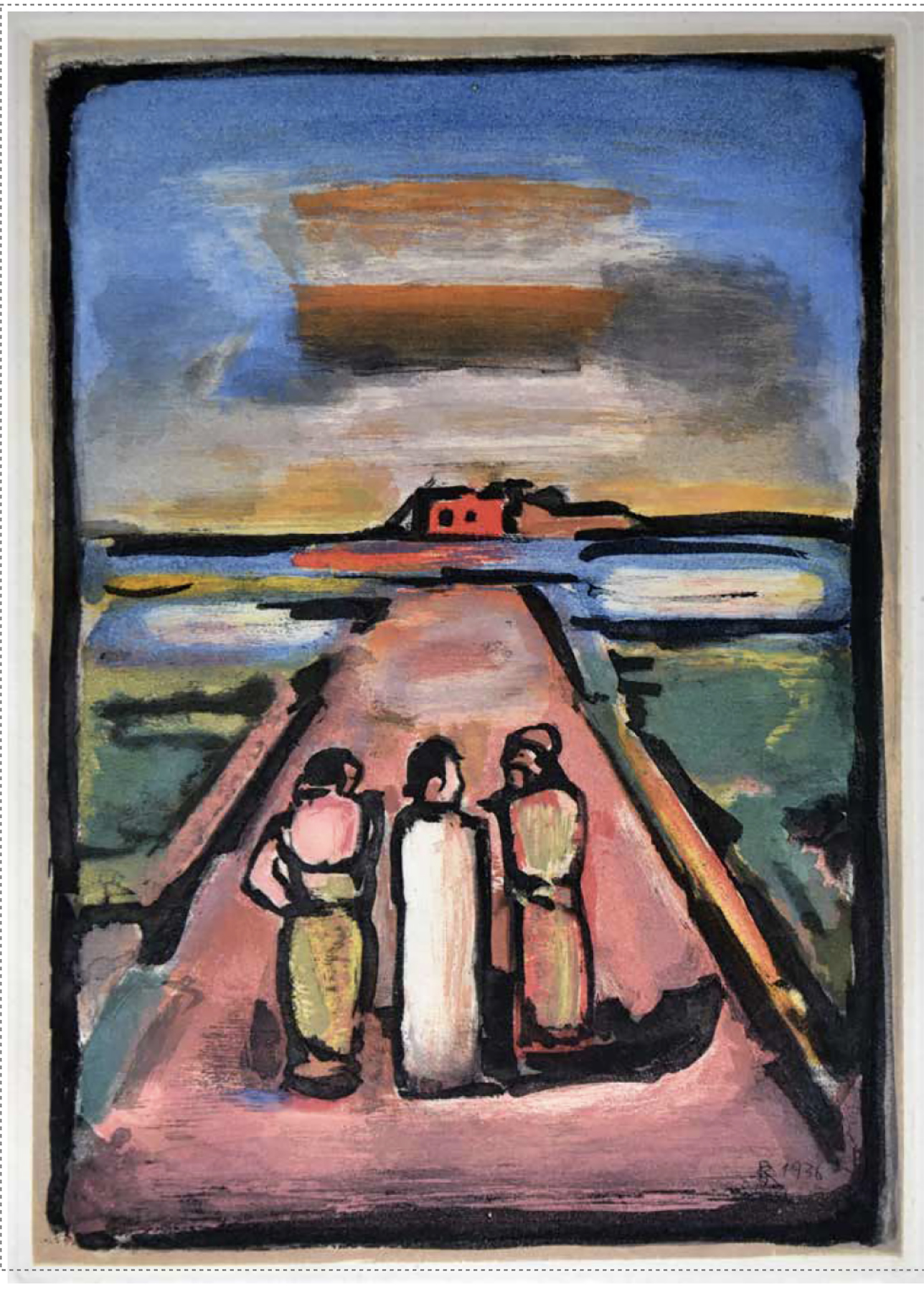

The work he had done as a young stain-glass maker influenced his style. Rouault loved and rooted himself in this medieval tradition, and his black lines filled with color were meant to act as a type of icon—a way to have the sacred and spiritual converse with the secular and material. Rouault said the eyes are “the doors of the spirit.” As his paintings contained Jesus with his disciples, with children, at his trial, and on the cross, Rouault desired to present the image of Christ as the true icon of the invisible. “His work had a meditative purpose in which the image is a medium for encounter between the visible and the invisible.” [10] Those paying attention, even meditating, on Rouault’s works, understand the light that shines out of the darkness and the unseen reality that is behind the seen reality in his paintings.

The homeless, clowns, prostitutes, and kings were also subjects of his portraits—all equal in symbolizing brokenness. As an observer of humanity, he painted his people as “fit objects of grace, while more visibly born in and for suffering.”[11] Sandra Bowden, artist and collector of Rouault’s work, stated in a talk on his Miserere series, “His work is not the easiest to appreciate because there is a darkness, a very realistic view of humanity, but there is always light in his work. But it is worth our effort to look deeply into the faces he portrays, to see how he portrays Christ being light in the middle of a world that has lost its way.”

As an artist rooted in medieval tradition and the Christian faith, Georges Rouault was a man of courage and fortitude. If courage is to act from the heart and an inner strength to work through challenging circumstances, fortitude “is the virtue that enables us to conquer the fears that stand between us and the good to which God calls us… it reminds us of our calling to suffer and sacrifice, patiently, day after day”[12] It is the long endurance. As Rouault once said, “The artist needs a great faith in the midst of indifference and hostility.” There are several areas where he lived out his calling, which he believed was from God, with courage and fortitude.

George Rouault placed himself in a long line of a medieval tradition. An apprentice in stain glasswork, he loved the materials and the colors. As a painter, he used black lines and bold colors to mirror the stain glass windows he created as a young man. As light shines through the colored glass in the windows, so did he backlight his color-filled paintings. As these medieval windows pointed the viewers to God, Rouault desired the same thing; “he wanted to portray Christ as the light in the middle of the a world that has lost its way.”[13] Rouault remained steadfast in this artistic vision, even when self-expression had become the only reason for an artist to create. No longer valid and valued were the medieval ideas of tradition as the means to grow in creativity and apprenticeship to a craft as a means for artistic training — except in Rouault’s vision for a life of painting. “In a sense. . . Rouault demonstrated that the highest form of self expression is to be had through the embrace of a tradition that is both open to the future and to God.”[14]

Another example of his courage and fortitude was his rejection of fragmentation found in new and popular artistic movements of his time, such as pursued by Pablo Picasso and Piet Mondrian. Where they painted in a way to make reality into two- dimensional spaces (also called Super-Flatism), George sought to paint wholeness and grace and the reality behind reality. “He brought synthesis out of an age of fragmentation. . . He was a little window that looked out into a vision of wholeness.”[15] As his faith in Christ grew, he kept to this vision of grace and wholeness by painting both the suffering of Christ and of humanity and the light of salvation found in a crucified and risen Savior.

Finally, a central aspect of his courage and fortitude was his enduring faith in God. “He made no distinction between religious and secular; to him everything he painted or created flowed out of his deep faith in God. . .He believed that his art flowed out of an interior life, so he maintained a solitary path, a lonely journey to depict the world as he saw it …he relied more on his faith as a guide for making his art.”[16] Painting was not about self-expression but following the call God had given him. Although his artwork and what he was trying to say was mostly misunderstood by the Catholic Church, all his work was religious. As one rooted in a medievalist mindset, he wanted his artwork to help others know God more fully. Curt Thompson in his upcoming book Soul of Desire says of Rouault, he was “a painter who, as a Christian, worked out the grappling of his inner-life through his art, pressed as it was between the world and the kingdom of heaven.” With compassionate eyes to the downtrodden and a belief in Christ on the cross, he linked the sufferings of Christ to the sufferings of humanity. George Rouault portrayed Christ as the hope in the darkness and the light behind light that will never be extinguished.

“The gaze of old Rembrandt or the death mask of Beethoven moves me as much as an entire century of heroic deeds. In reality, what is beautiful remains hidden and it has always been so. One must be worthy of searching for it and of persevering until death to find it. There will always be pain and anguish for whoever engages in this quest, but also profound and silent joy.”[17] George Rouault

The featured image is a detail of Les Disciples 2 by George Rouault.

[1] Charles Donelan, “Georges Rouault’s Miserere et Guerre: This Anguished World of Shadows” Santa Barbara Independent, September 6, 2007; https://www.independent.com/2007/09/06/georges-rouaults-miserere-et-guerre-this-anguished-world-shadows/

[2] Donelan, Charles, “Georges Rouault’s Miserere et Guerre: This Anguished World of Shadows” Santa Barbara Independent, September 6, 2007; https://www.independent.com/2007/09/06/georges-rouaults-miserere-et-guerre-this-anguished-world-shadows/

[3] Georges Rouault was one of the founders of the he founded the Salon d’ Atomen.

[4] Roach, Steven, Naming the Animals: An Invitation to Creativity, 2021 (Square Halo Books, Inc., Baltimore, MD) page 69

[5] Steven, Roach, Naming the Animals: An Invitation to Creativity, 2021 (Square Halo Books, Inc., Baltimore, MD) page 69

[6] Roach, Steven, Naming the Animals: An Invitation to Creativity, 2021 (Square Halo Books, Inc., Baltimore, MD) page 70

[7] Hibbs, Thomas S., Rouault – Fujimura: Soliloquies, 2009 (Square Halo Books, Inc., Baltimore, MD), 2009, page 29.

[8] Hibbs, Thomas S., Rouault – Fujimura: Soliloquies, 2009 (Square Halo Books, Inc., Baltimore, MD), 2009, page 23.

[9] Hibbs, Thomas S., Rouault – Fujimura: Soliloquies, 2009 (Square Halo Books, Inc., Baltimore, MD), 2009, page 58.

[10] Hibbs, Thomas S., Rouault – Fujimura: Soliloquies, 2009 (Square Halo Books, Inc., Baltimore, MD), 2009, page 49

[11] Hibbs, Thomas S., Rouault – Fujimura: Soliloquies, 2009 (Square Halo Books, Inc., Baltimore, MD), 2009, page 52

[12] Littlejohn, Brad, “Walking by the Light of Virtue in the Twilight of a Pandemic,” 2021 (Breaking Ground), https://breakingground.us/walking-by-the-light-of-virtue-in-the-twilight-of-a-pandemic/

[13] Bowden, Sandra, Notes for Georges Rouault Miserere Lecture

[14] Hibbs, Thomas S., Rouault – Fujimura: Soliloquies, 2009 (Square Halo Books, Inc., Baltimore, MD), 2009, page 43.

[15] Hibbs, Thomas S., Rouault – Fujimura: Soliloquies, 2009 (Square Halo Books, Inc., Baltimore, MD), page 55

[16] Bowden, Sandra, Notes for Georges Rouault Miserere Bowden, Sandra, Notes for Georges Rouault Lecture Lecture

[17] Nathanson, Richard, a’George Rouault 1871- 1958,” (Richard Nathanson website), 2021, https://richardnathanson.co.uk/artists/47-georges-rouault/works/

Leslie Anne Bustard takes great joy in loving people and places, whether at church, around her kitchen table, in a classroom, or traveling around. She delights in words, and marvels at the beauty found in the details of ordinary life. Reading, writing, teaching literature, baking, producing high school theater, and museum-ing are some of Leslie’s favorite things. Leslie is the host of The Square Halo, a podcast for Square Halo Books and is developing a book titled Wild Things and Castles in the Sky: A Guide to the Best Children’s Books. She and her husband Ned have been married for 30 years and live in a century-old row house in Lancaster City, where they raised their three daughters.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

It makes so much sense now–I see how his work in stained glass influenced his work! Years ago I created wih stained glass. All the bold color blocks separated by blackened foil. Thank you for this detailed, encouraging introduction. Appreciate Rouault’s courage to defend the oppressed and give them value as people, too.