LES: In your roles as poet, priest and rock n’ roller – a binding commonality is the word: the Word of God, the Word made flesh, and the word that weaves language and spirit together to make beauty and truth a part of our everyday life. You use words with extraordinary mastery not only express yourself but to heal and to redeem, very much in the fashion that the Lord does Himself.

Why have you pursued poetry as your venue? Why poetry instead of great fiction like LOTR or The Chronicles of Narnia? Those genres draw on ancient theme, myths, metaphor and work to heal and to illuminate. What is the compelling call of poetry and song-lyrics for you?

AMG: Well your phrase ‘compelling call’ is just the right one. There is something in poetry itself, in the magic of rhythm and rhyme, which woke me up, and called me. Reading certain poems I would feel something quickening in me, ‘my heart in hiding stirred’ to borrow a phrase from Gerard Manley Hopkins. Poetry, for me, always carries a sense of chant, and it is from chant that we get both, enchantment and chanson, both magic and song.

Of course there are other kinds of enchantment and other ways in which we can stir the imagination and produce an enhanced or transfigured vision of the world, and both LoTR and the Chronicles of Narnia are capable of that. But to write a great novel or a sustained work of mytho-poeic fantasy requires an architectonic vision and a sense of sweep and period which I don’t think I have. These are distinct from the gifts needed to be a lyric poet, which is my calling, though of course there are many things in common, and there is something magical and transformative about all imaginative writing whether in poetry or prose. Tolkien writes very well about this in his seminal essay On Fairy Stories. I was drawing on some of his phrasing and imagery in that essay when I wrote my sonnet Spell, as a sort of invocation of the magic potential of the twenty-six letters of the alphabet for all creative writers, but especially for the poet:

Spell

Summon the summoners, the twenty-six

enchanters. Spelling silence into sound,

they bind and loose, they find and are not found.

Re-call the river-tongues from Alph to Styx,

summon the summoners, the shaping shapes

the grounds of sound, the generative gramma

signs of the Mystery, inscribed arcana

runes from the root-tree written in the deeps,

leaves from the tale-tree lifted, swift and free,

shining, re-combining in their dance

the genesis of every utterance,

pattering the pattern of the Tree.

Summon the summoners, and let them sing.

The summoners will summon Everything.

LES: What is significant to you about the publication of Faith, Hope and Poetry? What does it represent in your life?

AMG: It was a long time in the making, but completing and publishing Faith, Hope and Poetry has proved something of a turning point in my life. As I mentioned earlier I had a few month’s sabbatical after seven years work as a parish priest and I found that what I most wanted to do was to re-immerse myself in poetry. In that intense few months, and the year that followed, I re-read the great treasury of English poetry from the Dream of the Rood in Anglo-Saxon through to the work of contemporaries like Seamus Heaney. It was immensely restorative and I found that it had renewed my vision and rekindled my faith. I began to share the experience through a series of lectures entitled Faith Hope and Poetry, which eventually grew into the book. But as the book grew I realized it was going to be more than just a collection of essays on favourite poems. I began to see that poetry was meeting a deep need in me and in others because there was a fundamental imbalance in our culture, an imbalance between reason and imagination, and that my book needed to be a defense of imagination and a plea for restored balance. In particular I saw the need to defend the role of imagination as a truth-bearing faculty, distinct from and yet complementary to reason, not just some private subjective mythmaking, but a real clue about how things actually are. So in the end the book became a bit of a manifesto, a rallying call to resist the bleak reductive materialism of our age, not only for the sake of the gospel as I understand it but for the sake of truth itself.

LES: Would you expand a bit on what Reverend Rowan William refers to as “the theology of imagination”? It sounds like it has a connection to C.S. Lewis’ phrase ‘a baptized imagination’ and yet those two are different things.

AMG: Well in some ways the phrase ‘theology of imagination’ goes right to the heart of what I was doing in Faith, Hope and Poetry. If I was to defend Imagination as a truth-bearing faculty I had to answer the questions, “Where does it come from?” “Why, and under what circumstances should it be trusted?” “What kind of truth is it telling us?” And to answer those questions required deep reflection on the doctrine of creation, on God as our maker, on what it means to say that we are made in his image, in the image of a maker, a creative artist. Reflecting on these led me from Creation to Incarnation, to what it means to say ‘the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us’. I began to see strong parallels between the urge to make and shape and create which is in our hearts and what the Bible tells us about God as a creator. And when I began to examine the accounts that poet’s give about what is going on in the act of imaginative creation I found that they all used essentially theological language. The key insight came when I realized that Shakespeare’s great description of the poetic imagination at work, (you remember the passage: ‘the poets eye …doth glance from heaven to earth from earth to heaven and as imagination bodies forth the form of things unknown the poets pen turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothingness a local habitation and a name’) I realized that this passage is in fact a description of incarnation, of a ‘word’, an ‘apprehension’ being ‘made flesh’ ‘bodied forth’ as Shakespeare says.

And so I came to see that the artist’s desire to incarnate a meaning in a particular embodied form is something that comes from God, something that is only possible because God has already done it and has made a universe in which it can be done, and that all successful artistic, imaginative embodiment of ‘the true the good and the beautiful’ involves participation in some degree in this primal act of God.

So that is something of what I mean by a theology of Imagination. Now the question of whether or not we have a ‘baptised imagination’, as Lewis used that term, is distinct, but not unrelated. Our imagination is, I believe, part of the ‘imago dei’, the image of God in us. But like every other part of us it is both God-given and at the same time shadowed and fallen. We can and do have what the Bible calls ‘vain imaginations’; false or empty shapings of the fantasy which merely serve the fallen isolated ego and do not participate, as imagination should, in the deep well springs that make and shape God’s good creation. So imagination needs to be cleansed and redeemed. And it seems to be that our own individual imagination is at least partly cleansed and redeemed when we enter into and enjoy the works of someone else’s redeemed imagination. That’s part of the good that good reading does for us and in us. So Lewis says that reading the great imaginative works of George Macdonald, and reading Milton and Spenser, had the effect of cleansing or ‘baptising’ his imagination! Even before the rest of his conscious and rational self was ready to acknowledge the truths of the gospel his imagination already apprehended in advance. In fact I came to realize that Lewis’s personal experience and the eventual healing and integration of the split between imagination and reason in his life was a symptom of the same split in the wider society of the modern age and therefore his healing and integration was also a tremendous and prophetic sign of hope that this deep split could also be healed in the wider society, that the baptized imagination could in the end bring the whole person, in all their faculties to baptism and renewal in Christ. In that sense just as the imagination is sometimes the forerunner of reason in our journey to faith, so I think Lewis, and the Inklings more generally are forerunners, showing in their lives and work how our wider culture can be healed and return to faith.

LES: What about your chapter in the Cambridge Companion to C.S. Lewis in which you wrote the chapter on Lewis as poet?

AMG: Well that was written after I had finished Faith, Hope and Poetry and in many ways it felt like a continuation of things I had discovered there, almost as if writing it had given me insights which allowed me to read Lewis’s poetry with new eyes and see how significant it really is. Lewis under-rated himself as a poet and he has been under-rated or ignored by the literary establishment. So my task in that chapter was to re-assess him, read him afresh in light of all that has happened in the worlds of poetry and wider society since he was writing and make the case for his relevance and importance now. If I have succeeded it was partly by re-assessing his poetry alongside that of TS Eliot and showing how much more they had in common than either was sometimes willing to admit, and also by showing that at the core of Lewis’s poetic vision was a project to re-integrate reason and imagination, both arising in us from the Logos, both necessary if we are to live fully freely. And that project of reintegration is even more necessary now than it was then. This is what I said near the end of that chapter:

“Lewis has sometimes been dismissed as archaic and out of touch but in retrospect his efforts in poetry, as in other fields, are much more contemporary and much more keenly directed to the crises of modernity that he has been given credit for. There are many complex links between his work and that of his two great contemporaries Yeats and Eliot. He is not perhaps a great poet in the same sense that they were, but he is a great deal better than the long neglect of his verse would imply. There is a clear internal coherence between all his efforts in every field. Taken together these efforts constitute an attempt at the redemptive re-integration of Reason and Imagination, the broken modes of our being and knowing.”

In fact the work on Lewis as a poet sent me back to all the Inklings with a new eye, and I began to see how much more radical and prophetic they are than is usually supposed, and my next book “The Inklings; fantasists or prophets?” is going to develop those ideas further.

LES: One of my favourite quotes is by Leonard Cohen. He said “Poetry is just the evidence of life. If your life is burning well, poetry is just the ash.”

Would you discuss the influence of “secular” poets (Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, Jack Kerouac) and how their work has acted as a bridge for you to see mystery, particularly in areas of life often considered “profane” and non-sacred?

AMG: I love Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan, and they have been very important to me throughout my adult life and indeed since my early teens. I’m glad you put the word “secular” in inverted commas. We need to think carefully about what we mean by that word. Clearly they are ‘secular’ in the sense that their work is not part of any sacred scripture, and they are not (usually) writing overtly religious tracts or ‘propagandising for any religious movement or church. Further, they are widely listened to and followed by people from any and every faith and none, all of whom find meaning and truth in their work. In that sense you can call them secular, but in another sense they are not secular at all. First because, like the rest of us they are made in God’s image and cannot help reflecting something of his truth and light, further they are, as poets, deep truth-tellers and truth belongs to Christ wherever it is found because He is Truth. Also since God became fully human in Christ, and took our humanity with him, wounds and all, into the heart of Heaven, then anyone who tells us honestly what it is like to be a wounded human being is telling us something about the experience of Christ and so of God. So even the most ‘secular’ writer may end up giving us insights into the sacred. There is something further of course about Dylan and Cohen, which is that they both have a deeply embedded Jewish heritage which has soaked right into their poetic imagination, deeply informed by the psalms, the prophets and wisdom literature, and then they have both, in their different ways, also absorbed the imagery and resonances of a Christian culture.

Certainly there are songs by both of them that feel like sacred music to me and are totally consonant with my understanding of life as a Christian. Cohen’s ‘That don’t make it junk’ for example, and Dylan’s Every Grain of Sand. The text of my paper on the religious roots of Dylan’s work is here: http://malcolmguite.wordpress.com/new-writings/

Kerouac is another writer whom most might think of as ‘secular’ or even profane but whose writing is paradoxically rich in spiritual insight. My appreciation and understanding of Kerouac has been taken to a new level through my friendship with Gerry Nicosia, the author of the brilliant Kerouac biography Memory Babe and now a new book about on the road. When I was in San Francisco to do some poetry readings with him he took me on a Kerouac pilgrimage and we talked together about how deeply embedded Christian catholic imagery was in Kerouac’s imagination, especially images of angels and Our Lady. He took me to the church where Jack and Neal Cassady were suddenly moved to pray together and we thought about how Saint Francis was in some ways a proto beat! I gathered some of these memories into my poem ‘cloud-hidden‘.

LES: In the interview with The Journal of the Duke Divinity School, July 21, 2009 you made a comment – “The poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge said that ‘a poet is a person who takes the vision of the child into the powers of the adult.’ It’s the expression of a childlike vision through adult powers” reminds me of a comment made by Michael Ward in a recent podcast the original meaning of “poet” is maker. Is there some further light you could shed for us on that concept of Poet as Maker and Creator?

What would you say the role of the poet is in contemporary culture? Is it different now, in your opinion than it was, say two or three hundred years ago?

AMG: The Greek verb poiein means ‘to make’ and so poets are indeed Makers, and shapers. In earlier cultures that role and its wider benefit to the whole community was much clearer. Poets kept and shaped the great stories, the mythoi that bound people to life , that reconnected them both with the sacred and with their own inner being. And that, in my view continues to be the role of true poetry, in its widest sense today. And in the wider sense of poetry I would include the great story telling in novel and film and the other making and shaping arts. But the specific role of a poet, as a maker and shaper in words, a chanter and enchanter of language, has become more problematic. That is partly because many (though not all!) modern poets have ceased either to chant or to enchant. Like other modern artists, they have been so impressed and distressed by the fragmentation of our culture, the prevailing mood of alienation, absurdity, and crisis of meaning, that they have, in some sense capitulated to it and made poetry which is itself so broken, alienated and sometimes deliberately ‘unmeaning’ and obscure that many people have simply ceased to read it! I think this is bad, both for those individual poets and for poetry itself. In previous ages poets were central to life and culture and were looked to as a source of Wisdom and these poets always acknowledged that the wisdom in their poetry was mediated through them, that it did not entirely originate in them as persons. The last great poet in England who could truly have been considered a national poet, someone who was central to the whole life and culture of the nation who ‘purified the dialect of the tribe’ who articulated our deepest longings, but also brought us warning and prophecy, and was widely read and popular, was Alfred Lord Tennyson. I admire Tennyson because although his poetry was popular and widely accessible, it was also beautifully wrought, full of great latent meaning that would only emerge after many readings, and capable of dealing with the darkest of human experiences as well as the most joyful, as in In Memoriam for example. Tennyson shows that you don’t have to be obscure to be profound and that being lucid is not the same thing a being trite.

I hope that in the end modern poetry will re-emerge from a period of willful obscurity, ugliness and ‘difficulty’ and dare again to sing clearly, to chant and enchant, and there are of course some really great poets in our own age who already do that; Seamus Heaney, Derek Walcott, Ceslaw Milscz , Wendell Berry and Mary Oliver among them. In fact I think there are more signs of hope in the North American poetic scene, with the consistently lucid and beautiful poetry of writers like Luci Shaw, Madeleine L’Engle and Dana Gioia than on this side of the pond where many poets seem still to be trapped in the cage of tricksy, self-referential post-modernism.

I think a change is coming, and poetry will have the confidence again to write clearly on the open page of life and when that happens people will return to the poets, seeking and finding what Heaney has beautifully called: a draught of the clear water of transformed understanding and fills the reader with a momentary sense of freedom and wholeness.” (The Redress of Poetry page XV)

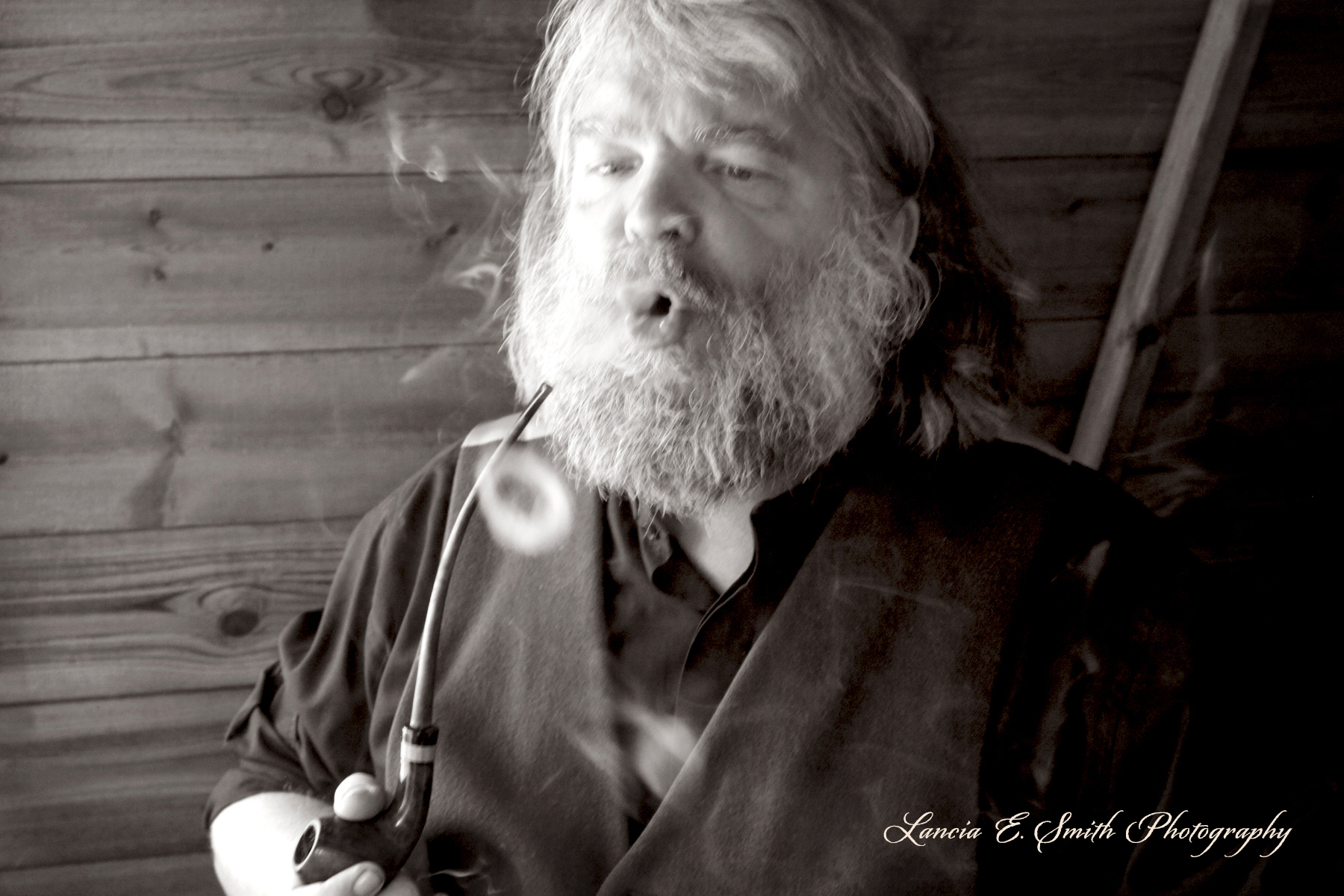

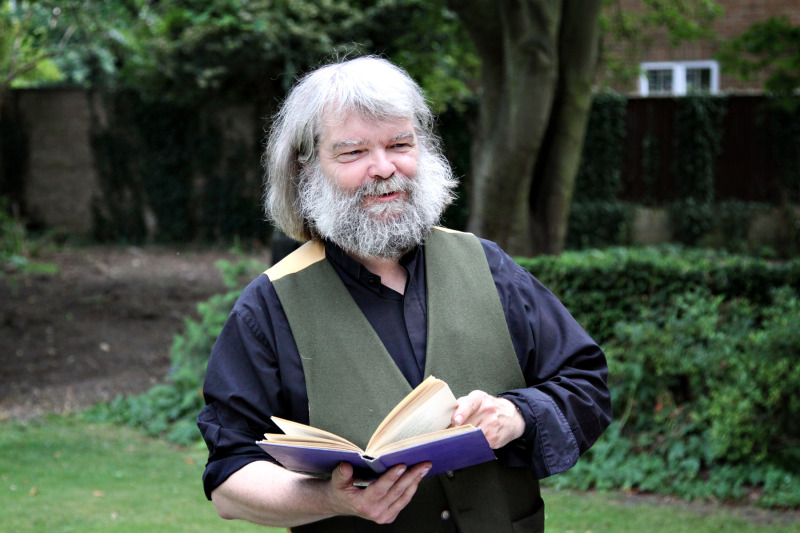

All the images included in this interview are courtesy of Lancia E. Smith and used with my glad permission for Cultivating.

To continue further discoveries with Dr Guite, here is a link to a complete set of interviews shared with readers of Cultivating.

Blessings to you and every grace!

Lancia E. Smith is an author, photographer, business owner, and publisher. She is the founder and publisher of Cultivating Oaks Press, LLC, and the Executive Director of The Cultivating Project, the fellowship who create content for Cultivating Magazine. She has been honoured to serve in executive management, church leadership, school boards, and Art & Faith organizations over 35 years.

Now empty nesters, Lancia & her husband Peter make their home in the Black Forest of Colorado, keeping company with 200 Ponderosa Pine trees, a herd of mule deer, an ever expanding library, and two beautiful black cats. Lancia loves land reclamation, website and print design, beautiful typography, road trips, being read aloud to by Peter, and cherishes the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and George MacDonald. She lives with daily wonder of the mercies of the Triune God and constant gratitude for the beloved company of Cultivators.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

Thank you so very much, Lancia, and Revd. Dr. Guite, for this rich and inspiring interview series. Indeed, the rich and varied sweep of your discussion with him makes it difficult to leave a comment that encompasses my sense of refreshment and excitement. Suffice it to say that I just finished reading most of this last interview aloud to my daughter, who just graduated from college on Sunday with a degree in English and journalism, and is herself a lover of C.S. Lewis’ writing and an aspiring writer.

If I was forced to choose a favorite bit from this interview, I think it would be this:

“In fact I came to realize that Lewis’s personal experience and the eventual healing and integration of the split between imagination and reason in his life was a symptom of the same split in the wider society of the modern age and therefore his healing and integration was also a tremendous and prophetic sign of hope that this deep split could also be healed in the wider society, that the baptized imagination could in the end bring the whole person, in all their faculties to baptism and renewal in Christ. “

Leslie, thank you so much for your enthusiastic reading and commenting. It is a joy to have readers like you! I loved that same line from the interview!

This interview is a good taste of what we do at The C.S. Lewis Retreat and I think you would find that it would be right up your alley and your daughter’s. It is the place to be for those of us who love Lewis, love what he loved, and are passionate readers, writers, and mere Christians. Let me know if you would like more information about it. Malcolm has been one of our most beloved speakers and a strong supporters!

[…] Part 3 Poetry and the role of the poet Why have you pursued poetry as your venue? Why poetry instead of great fiction like LOTR or The Chronicles of Narnia? Those genres draw on ancient theme, myths, metaphor and work to heal and to illuminate. What is the compelling call of poetry and song-lyrics for you? […]

[…] Our close friend, staff member, and sometimes photographer, Lancia E. Smith, just concluded her seri… Don’t miss this fascinating interview about poetry, faith, music, teaching, C.S. Lewis, the Inklings, Malcolm’s life, and other tidbits of goodness, truth, and beauty. […]

Thank you so much to the both of you. I began to love the power of words when I first read His word. I am always grateful to encounter the divine spirit (that sweet glimpse) in others, as I have here once again. And not least, “Spell” is a wonderful poem.

Thanks again, Markkur

Thank you, Markkur, for your kind words! ‘Spell’ is very beautiful and I am delighted to find a fellow enthusiast.:-) Blessings to you.

[…] Click here for Part 2 and Part 3 […]

[…] Interview with Malcolm Guite – Part 3! […]

[…] 2012 Interview with Malcolm Guite – Part 3 […]

[…] 2012 Interview with Malcolm Guite – Part 3 […]

March 24, 2023

Dear Ones,

I am way past catching this train, but I’m grateful that a friend gave us the Daily Poems for Advent and Christmas. The blessings that have flowed from the poems and commentary have ignited a freshness to our pilgrimage journey in this vale of tears we have experienced for the past several years.

“In the morning, fill us with your love; we shall exult and rejoice all our days. Give us joy to balance our affliction for the years when we knew misfortune.” (Psalm 90:14-15)

The daily reading and praying Psalms from the Liturgy of Hours has brought and intimacy with the Lord that has deepened. Thank you, Malcolm, I have been greatly blessed with ministry the Lord has given you. So much more to write, but this should suffice to let you know, Lancia Smith, that the interviews with Dr. Guite, even though that was 11 years ago, have gently tilled the soil of my latter years.

Thank you!

Sincerely,

Ronald Davis