Grace is not a new idea to me. I was baptized in a church named Grace. There, in sermons and Sunday school the word “grace” was used again and again. In the catechism I was taught that “Grace is the unmerited favor of God.” And yet after all of that instruction, I do not think I really understood what grace meant.

Another thing I thought I understood but did not really have a grasp on was abstract art. I had graduated from college with a degree in art, yet had no time for non-representational art. I am an illustrator and graphic designer. In both visual pursuits I am zealous to be representational and clear in communicating what I am trying to say. However, on a train one night in the early 2000’s, coming home from New York City with a slim art catalog in my lap titled Images of Grace, my eyes were opened to the beauty of abstract art. As I stared at one work in particular, titled Common Grace, things began to change.

The painting had the faintest hint of a tree growing out of a landscape consisting of white with gold leaf. The “leaves” of the tree were squares of gold leaf bleeding into a “sky” of blues and greens and blacks, over which the words from Psalm 19:1-4 were delicately traced in handwritten gold letters.

The art made by Makoto Fujimura was a synthesis of Western aesthetics and Nihonga—a medieval style of painting from Japan. His art has been featured widely in galleries and museums around the world. We became connected when I was developing my first book, It Was Good: Making Art to the Glory of God. [1] Mako has an essay in the book and his painting Grace Foretold is featured on the back cover.

Over the years it has been a joy to become friends, and Mako has been very generous to me. Yet that night on the train he gave me a gift without even knowing it. Along with Common Grace, I drank in his other paintings in the book including Costly Grace, Tree Grace, and more. [2]

Around the same time I was experiencing Mako’s grace works, I also was involved in a church plant [3] through which I was introduced to what grace really is. Yes, grace is the unmerited favor of God, but the reality of that truth is so much deeper and richer than the catechism can capture. As a covenant child who grew up in the faith, it was remarkable to hear messages like from Paul Miller: “Cheer up; you’re a lot worse off than you think you are, but in Jesus you’re far more loved than you could have ever imagined.” And to learn what adoption by God could mean to me, to allow me to “enjoy the liberties and privileges” [4] —the glorious freedom of being a child of God.

Yet even as my heart began to appreciate the life-changing reality of grace, I continued to need explanations. Through Dr. Timothy Keller the concept of grace began to blossom. Among the things that Keller taught me through many of his books and sermons was that:

The Bible’s purpose is not so much to show you how to live a good life. The Bible’s purpose is to show you how God’s grace breaks into your life against your will and saves you from the sin and brokenness otherwise you would never be able to overcome… religion is “if you obey, then you will be accepted.” But the Gospel is, “if you are absolutely accepted, and sure you’re accepted, only then will you ever begin to obey.” Those are two utterly different things. Every page of the Bible shows the difference. [5]

In a similar way, to understand Mako’s abstract art I needed the teachings of art historian Dr. James Romaine [6] to really unfold it for me. To explain Mako’s art, James Romaine coined the phrase “arenas of grace.” Romaine used this phrase because he was trying to rebut the idea of our friend’s art being simply decorative. Although beautiful enough to elevate even the most deplorable of spaces, Mako’s art is far more than simply pretty—it is transformative. To walk away from having looked at his art unchanged simply means you did not look at the work long enough. Mako’s “arenas of grace” are constructed by layers of pigment being applied on the surface of handmade paper, over which more layers of crushed minerals and layers of gold and ink and sometimes words floated. Stepping into those layers of beauty and experiencing all those layers united in one image is stepping into the arena of grace.

The arena of grace is both in the image Mako created and the experience of encountering that work as a whole. Entering the arena changes you. You do not leave the arena the same person.

At first glance a painting in the Images of Grace might appear to simply be a tree standing against a moody sky. But when we stop and spend time looking with intention, we find on the surface the gesture of a tree, but also floating behind that painterly stroke is a luminous cloud, an undulating world of colors, and morphing shapes. And all of these elements float over the surface of the delicate paper that forms the foundation on which the cacophony of colors and washes and strokes and shapes dance.

To spend time with one of Mako’s paintings is like walking down into a canyon, passing ribbon after ribbon of different colors of rock.

Or perhaps instead, floating down deeper and deeper into the depths of the ocean, finding subtle changes in intensity of the water’s blues and greens as they undulate with an unexpected rhythm.

My description of these paintings might lead the reader to think that these “arenas of grace” are dependent on an intoxicating amount of color. That is not always the case. The impact of Mako’s work in creating these transformative spaces can be experienced even in much more monochromatic works. For example, hanging over my bed is a lithograph Mako made called Shalom. [7] It is a piece he created immediately following the 9/11 attacks. It is like a tree—as a righteous man is like a tree planted by streams of water—but it is also not . . . and also more.

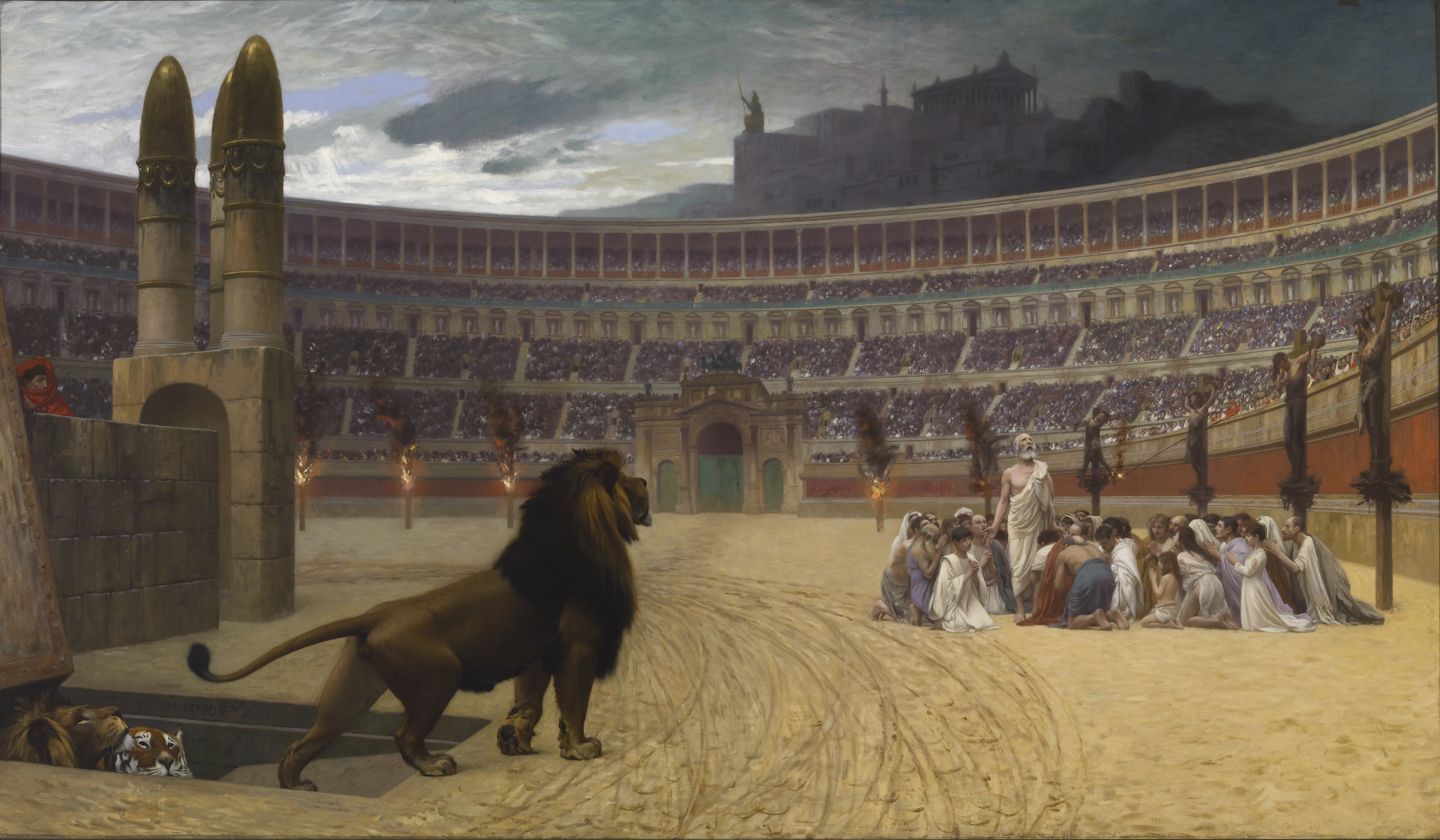

Like grace itself, the art of Mako Fujimura requires much more of us. Both take you into an arena. The early Christians knew about arenas. Their “arena of grace” was the Colosseum. [8] They did not go in and come out unscathed. In the same way, an encounter with actual grace leaves its mark. How can the prodigal son remain unmoved by the embrace and celebration of his return by his father? Grace changes you. There is a theological term that pastors sometimes use: “efficacious grace,” which basically means “grace that gets the job done.”

Therefore, when we think about the grace of God, we must understand that it will be successful in producing the Father’s intended result. Tim Keller taught, “God sees us as we are, loves us as we are, and accepts us as we are. But by His grace, He does not leave us as we are.” [9] God will see the work He began in you is finished (Philippians 1:6). And if you find that grace is not “efficacious,” that it is, grace is not working its change in your life, maybe you need to go back—like I had to go back to the paintings of Makoto Fujimura—and look again.

Allow yourself to be swept up into the arena of grace.

![]()

[1] Ned Bustard, ed., It Was Good: Making Art to the Glory of God (Baltimore, MD: Square Halo Books, 2007); https://www.squarehalobooks.com/#/it-was-good-art.

[2] View some of these pieces at https://makotofujimura.com/art/images-of-grace. You can also find examples of Mako’s artwork in It Was Good: Making Art to the Glory of God, Objects of Grace: Conversations on Creativity and Faith, and Faith + Vision: Twenty-five Years of Christians in the Visual Arts—all published by Square Halo Books.

[3] https://www.wheatlandpca.org.

[4] Westminster Confession of Faith, Article 12 ( https://www.pcaac.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/WCFScripureProofs2022.pdf )

[5] https://bible-daily.org/2009/04/28/the-bibles-purpose/

[6] James Romaine, Objects of Grace : Conversations on Creativity and Faith (Baltimore, MD: Square Halo Books, 2002);

[7] View it here: https://artway.eu/content.php?id=1227&lang=en&action=show.

[8] Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer (1883); Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD; https://art.thewalters.org/detail/36782/the-christian-martyrs-last-prayer/

[9] Ned Bustard, ed., The City for God: Essays Honoring the Work of Timothy Keller (Baltimore, MD: Square Halo Books, 2022); https://www.squarehalobooks.com/#/the-city-for-god/

The featured artwork, “The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer” (1883) was painted by Jean-Léon Gérôme.

Ned Bustard is a graphic designer, children’s book illustrator, author, and printmaker. Some of the books include Bible History ABCs: God’s Story from A to Z, Revealed: A Storybook Bible for Grown-Ups, History of Art: Creation to Contemporary, The O in Hope, Saint Nicholas the Giftgiver, The Light Princess, The Lost Tales of Sir Galahad, and volumes I–III of Every Moment Holy.

Ned is the creative director for World’s End Images and Square Halo Books, Inc., curates the Square Halo Gallery, is an elder at Wheatland Presbyterian Church, and serves on the boards of both the Association of Scholars of Christianity in the History of Art (ASCHA) and The Row House, Inc.

He has three daughters, two dogs, and an unreasonable amount of books. Ned lives in the West End of Lancaster, Pennsylvania—much too far inland for him to get to go sailing. Learn more at www.WorldsEndImages.com

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

Great post Ned! I love the mention of “efficacious” grace, and the picture of God as the faithful, compassionate, and loving pursuer, intent on grace becoming far more than an intellectual assent. I’m also reminded of how missional and even prophetic art can be when it focuses on “embodying” truths.